SUMMARY

LAWMAKING

On State Security

On Discrediting and “Fakes”

On

Extremism

On

Control over the Internet

On

Non-Profit Organizations

LAW ENFORCEMENT

Sanctions

for Anti-Government Statements :

Calls

for Extremist and Terrorist Activities : Incitement

of Hatred : Displaying

Banned Symbols : Discrediting

the Military and Government Agencies : Spreading

“Fake News” about the Special Military Operation Motivated by Hatred : Other Anti-Government Statements : Vandalism Motivated by Hatred : Hooliganism Motivated by Hatred

Involvement in Banned Oppositional Organizations :

Persecution

of Alexei Navalny and His Supporters : Sanctions against Vesna Movement Participants

Banning Oppositional Organizations

The State on Guard of Morality :

Sanctions for “Rehabilitating Nazism” : Ban on the “International LGBT Movement” : Sanctions for Insulting the Religious Feelings of Believers

Persecution against Religious Associations :

Jehovah’s Witnesses : Scientologists : Allya-Ayat : Hizb ut-Tahrir : Followers of Said Nursi : Tablighi Jamaat

A BIT OF STATISTICS

Summary

This report presents an analytical review of anti-extremist legislation and its misuse in 2023.[1] SOVA Center has been publishing these reports annually to summarize the results of monitoring carried out by our center continuously since the mid-2000s.

We define anti-extremist legislation as the policy of criminalizing actions that are politically or ideologically motivated in a broad sense. Our analysis goes beyond the formal framework – we also monitor restrictions relating to acts not classified by the law “On Countering Extremist Activities” as “extremist crimes.”[2]

The trends that emerged in 2022, when efforts by all three branches of government to maintain control over society focused on suppressing anti-war protests, generally continued in 2023. Despite these efforts, various protest activities also continued in 2023, but individually or in small groups rather than as mass events.

Legislation in our area of interest developed less rapidly than a year earlier, although we cannot say that the repressive legislative potential was exhausted in 2022. Deputies simply did not introduce new norms but expanded and tightened existing ones. The new legislative activity included amendments to articles that covered discrediting the army, “fakes” about the army, and attempts to establish responsibility for justifying extremism, newly introduced fines to social networks for evading content moderation, and amendments to the legislation on NGOs. However, in addition to that, several entirely new norms were incorporated into the Criminal Code (CC) and the Code of Administrative Offenses (CAO).

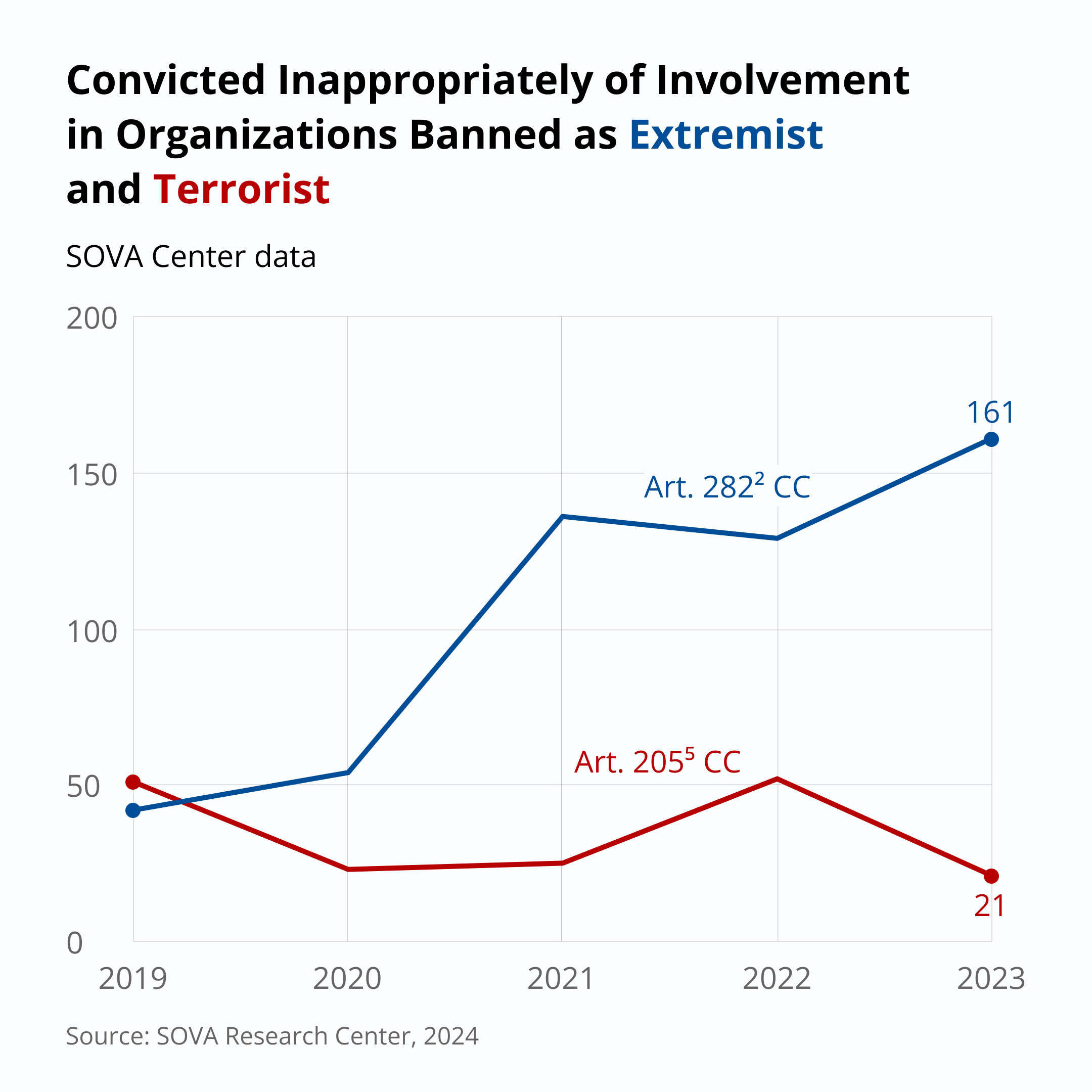

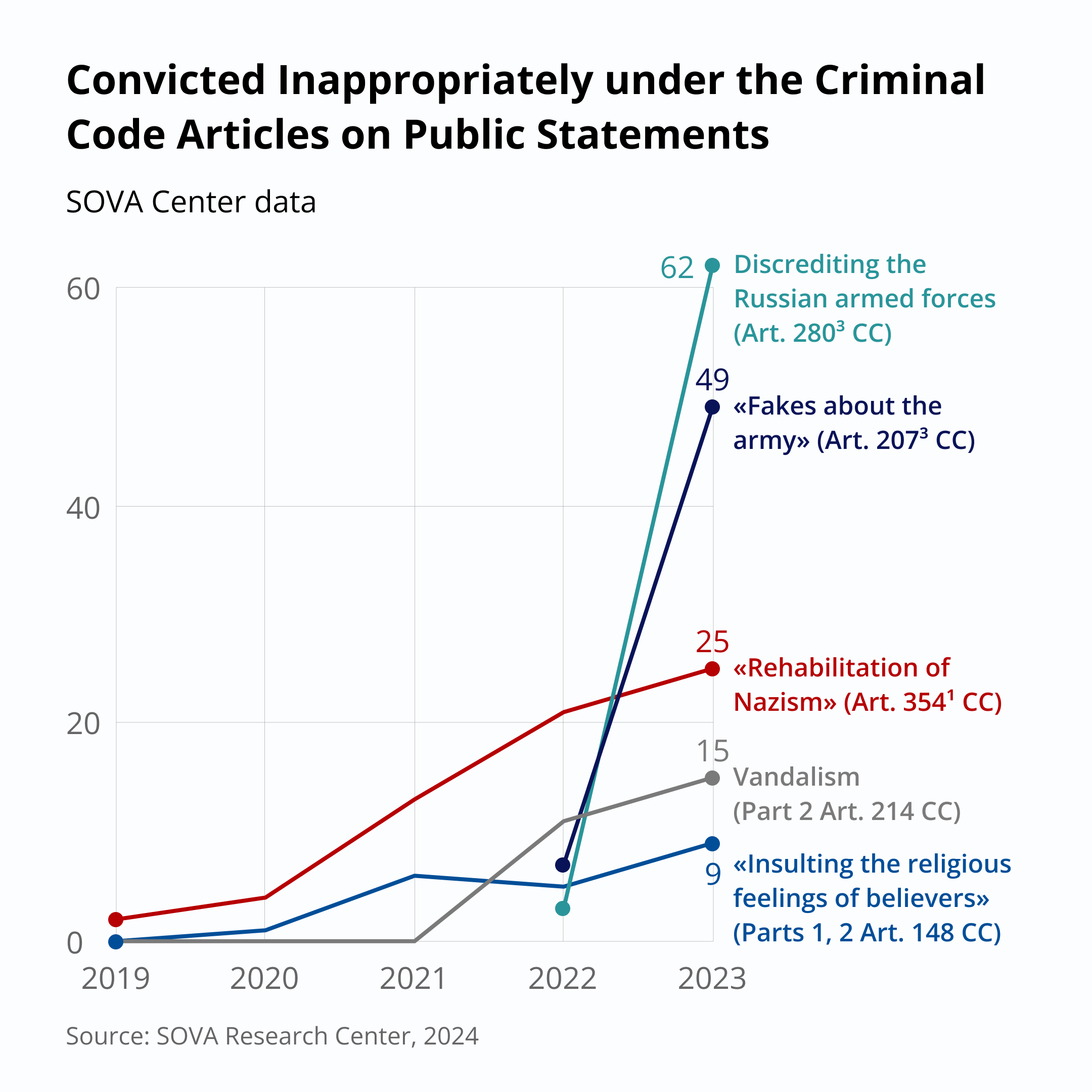

The widespread implementation of repressive law enforcement, as detailed in our report from a year ago, naturally influenced the number of sentences handed down in 2023. As of the publication of this report, our records indicate that 360 people were convicted in 2023 (compared to 240 in 2022) under anti-extremist and related articles without proper grounds. Additionally, we noted another 350 individuals (compared to 265 in 2022) facing charges whose cases have not yet proceeded to trial.

The above number includes 172 people arbitrarily convicted for public statements (compared to 55 in 2022) and 195 convicted for involvement in banned organizations' activities (compared to 185 in 2022), with the majority of these cases involving religious associations. Thus, we see that both the total number and the percentage of individuals convicted for speech have increased sharply. This increase can be attributed to the widespread application of criminal provisions in cases involving repeated discrediting and “fakes” about the army, opened back in 2022, that reached the courts in 2023. We also noted a large number of inappropriate convictions under articles on the rehabilitation of Nazism, mostly for disorderly conduct at the Great Patriotic War memorials and for anti-war actions that were qualified as vandalism motivated by political or ideological hatred.

Targeted sanctions against opposition activists persisted throughout the year, with a noticeable increase in the number of individuals charged in the “extremist community” cases against Alexei Navalny and his supporters. The court sentenced Navalny to 19 years in prison; while serving this sentence, he died in a maximum-security penal colony in February 2024. Several regional coordinators of his headquarters also received harsh sentences. Approximately 20 activists of the Spring (Vesna) movement were charged with organizing an extremist community.

The persecution campaign against Jehovah's Witnesses continued throughout the country throughout the year and even intensified compared to the previous year. 153 believers were sentenced (vs. 116 a year earlier), and at least 107 more became involved in new criminal cases (compared to at least 77 a year earlier).

The number of cases under anti-extremist articles of CAO decreased in 2023, in particular, we saw a sharp drop of almost 50% in the cases under the article on discrediting the army, which was so popular a year earlier. The change is due to the above-mentioned absence of mass anti-war actions. Meanwhile, the equally numerous sanctions for displaying prohibited symbols remained at approximately the same level. In this report, we note inappropriate punishments for the publication of images with swastikas used as a means of visual criticism of the authorities and for Ukrainian slogans and symbols. People continue to face sanctions under the administrative article of incitement to hatred for expressing strongly worded criticism of the president, officials, and law enforcement officers.

Moscow became the absolute leader in the number of wrongful convictions in 2023, primarily due to verdicts on the dissemination of “fakes” about the army motivated by hatred. Such verdicts were issued in large numbers in absentia against prominent residents of the capital, who have left Russia – public figures, journalists, political scientists, etc. In general, prosecution and imprisonment of prominent opponents of the regime for their public statements, including anti-war ones, has become a trend in the last two years. It could be argued that the authorities use “show trials” as a means of ideological prevention. High-profile examples of such cases include the cases of Igor Strelkov and Boris Kagarlitsky, who opposed the authorities from opposite sides of the political spectrum, for incitement to extremism and justification of terrorism respectively; the case of theater director and author of famous anti-war poems Evgenia Berkovich and her colleague screenwriter Svetlana Petriychuk on trumped-up charges of promoting Islamic terrorism; and criminal charges against Oleg Orlov, a co-chair of the HRDC “Memorial” for the repeated discrediting of the army.

Crimea ranked second among regions in terms of the number of arbitrary convictions. While Moscow saw more sentences issued under articles related to public statements, Crimea had a higher number of cases related to involvement with the Islamic party Hizb ut-Tahrir, recognized as a terrorist organization in Russia.

Crimea was among the leaders in the number of those facing administrative sanctions illustrating another important trend of the past two years, particularly noticeable on the peninsula: the increased activity of initiative groups aligned with law enforcement agencies. These groups identify fellow citizens perceived as disloyal to the authorities and file legal complaints against them.

Overall, the search for internal enemies—a characteristic manipulation tactic of authoritarian regimes—is increasingly entrenched in the country as a daily practice. The apex of the Russian authorities' efforts to uphold moral purity in 2023 was the ban imposed on the “international LGBT movement” as an extremist organization. This ban effectively stripped LGBT individuals of the opportunity not only to openly advocate for their rights but also to live their lives without hiding or constant risk of persecution.

Lawmaking

In 2023, new norms were adopted, continuing the course set in the preceding year and directly related to military actions in Ukraine. These norms were primarily aimed at supporting state security and combating any form of obstruction against the “special military operation.”

On State Security

In April, the president signed a law that increased responsibility for sabotage and terrorist crimes[3] and introduced a new legal norm into the Criminal Code against assisting foreign entities that prosecute Russian officials and military personnel. The new Article 2843 CC punishes “assistance in carrying out decisions of foreign government entities or international organizations, in which the Russian Federation does not participate, that involve criminal prosecution against government officials of the Russian Federation in connection with their official activities, or against other persons in connection with their military service or participation in volunteer formations that contribute to the fulfillment of the tasks assigned to the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation.” At the same time, the effect of Article 2804 CC (public calls to carry out activities directed against the security of the state) was extended to calls to commit a crime under the new Article 2843 CC.

In the same month, the president also signed a new federal law “On Citizenship of the Russian Federation.” Among other considerations, this law clarifies and expands the grounds for terminating Russian citizenship acquired either by application or as a result of a federal constitutional law or an international treaty. The grounds include a court verdict, which has entered into legal force, issued under one of the Criminal Code articles specifically listed in the law. The list includes many articles regulating and limiting public statements and events, as well as organizational activities.[4] Thus, according to the new law, offenders convicted under a wide range of Criminal Code articles can be deprived of their acquired Russian citizenship. Some of these norms, in our opinion, should not have been introduced at all, while others have been poorly worded, and still others are often applied inappropriately. We also believe that many crimes covered by the articles later added to the list do not pose sufficient danger to society to warrant depriving people who committed them of their acquired Russian citizenship. It should be noted that many people who acquired Russian citizenship at some point in their lives have no other citizenship at this point; some of them have lived in Russia since childhood. Separately, we should pay attention to the fact that the procedure for canceling the decision to grant citizenship will also apply to residents of territories recently annexed to Russia who have acquired Russian citizenship, starting with Crimea.

Another basis for the termination of citizenship is “committing actions that pose a threat to the national security of the Russian Federation,” and the statute of limitations does not apply to these offenses. The FSB is expected to submit a conclusion that such actions indeed took place. Previously, a temporary residence permit could be revoked based on undisclosed FSB orders, and now this practice will expand to revoking one’s citizenship. This norm reinforces the department’s full discretion over an issue that affects basic human rights.

The adoption of the new law on citizenship did not stop the flow of new parliamentary initiatives in this area. Some even proposed depriving offenders of their birth citizenship on the same grounds in order to bring the rights of all Russians in line with those of residents of the annexed territories, but this idea did not receive support.

On Discrediting and “Fakes”

Legislators continued to pay particular attention to suppressing criticism of the special military operation.

Thus, according to the laws signed in March, public dissemination of knowingly false information and repeated discreditation are criminalized not only when pertaining to activities of the armed forces and Russian state bodies abroad but also to activities of volunteer formations, organizations, and individuals, who support the armed forces of Russia in carrying out their assigned tasks.

Meanwhile, sanctions under Article 2073 Part 1 CC became more severe with the maximum punishment under it increasing from three to five years of imprisonment. The change meant that the acts punishable under Part 1 of both articles ceased to be a crime of minor gravity. Therefore, it became possible to use arrest as a preventive measure and impose real prison terms in the absence of aggravating circumstances. The terms of imprisonment under Article 2803 Part 2 CC (discreditation of the army resulting in death by negligence and (or) causing harm to the health of citizens, property, mass violations of public order, and (or) public security) increased from five to seven years of imprisonment. The terms under Parts 2 and 3 of Article 2073 CC remained the same, from five to ten and from ten to fifteen years of imprisonment respectively.

Liability under Article 20.3.3 CAO, used to punish public discreditation committed for the first time in 12 months, was expanded to statements about volunteer formations, individuals, and organizations that contribute to the fulfillment of the Russian Army’s objectives. The punishment under this article remained the same.

In December, the President signed two laws to expand the scope of Article 20.3.3 CAO, Article 2803, and Article 2073 CC, as well as the recently introduced Article 2843 CC, which punishes assistance to international organizations in executing their decisions on criminal prosecution of Russian officials and military personnel. Volunteer formations, which the Russian Guard had been authorized to create, also came under the protection of all these norms.

We should also note that in May, the Constitutional Court of Russia issued rulings refusing to accept for consideration 13 complaints by citizens against Article 20.3.3 Part 1 CAO that the claimants saw as violating their constitutional rights. The applicants argued that the clause on “discrediting” was discriminatory and violated their rights to freedom of speech, the right to freedom of assembly, and the constitutional prohibition on the introduction of compulsory ideology. They emphasized that the state could not rank value judgments and beliefs as correct or incorrect, and criticism of the use of the military should not form the basis for stigmatization and ostracism. The Constitutional Court ruled that this article does not contradict the Russian Constitution. The court found that the article used the concept of discreditation in its generally accepted meaning, “undermining the confidence of individual citizens and the society as a whole in someone's actions (activities).” According to the Constitutional Court, the assertion that decisions of state bodies are motivated by the need to protect the interests of Russia, peacekeeping and security considerations should not be questioned “arbitrarily, solely based on subjective assessment and perception,” and, additionally, the military requires public support to uphold their morale and psychological condition. A negative assessment made in public can “support the forces that oppose the interests of the Russian Federation and its citizens,” even if the author of the statement had no such intent. The Constitutional Court believes that Article 20.3.3 CAO does not introduce a mandatory ideology, is not aimed at war propaganda, is not discriminatory, and does not encroach on the freedom to hold certain beliefs, “because such freedom does not presuppose that a person commits an offense. The latter assertion by the Constitutional Court could be construed as permitting any additional limitations on freedom of belief, if a law categorizes the expression of certain beliefs as an offense, regardless of the limitations’ compliance with the Constitution. This approach calls into question the very purpose of the Constitutional Court.

The order of the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs changing the instructions for the community police inspectors was signed in November. The innovations included imposing on district police officers the responsibility to carry out individual preventive work with citizens who have committed administrative offenses under Article 20.3.3 or Article 20.3 (public display of prohibited symbols). Those facing responsibility for offenses that infringe on the order of governance, committed during public and sports events, also became subject to preventive efforts – primarily for the offenses under Article 19.3 CAO (disobeying a lawful order of a police officer). Previously, prevention measures targeted offenders charged after public events specifically under Article 20.2 CAO (violation of the procedure for holding public events) or Article 20.31 CAO (violation of rules of conduct by spectators at sporting competitions).

On Extremism

Deputies from the United Russia party took another decisive step in the fight against extremism in 2023. In July, a bill was introduced to the State Duma to expand the scope of Article 280 CC, which covers public calls for extremist activity. The deputies suggested that the article should also cover public justification and propaganda of extremism. In addition to changing the scope, the deputies proposed to supplement Article 280 CC with notes to provide definitions of justification and propaganda of extremism similar to those found in Article 2052 CC (public calls for terrorism, public justification of terrorism, or propaganda of terrorism). They proposed to define public justification of extremism as “a public statement that recognizes the ideology and practice of extremism as correct and deserving of support and imitation,” and propaganda – as “the activity of disseminating materials and (or) information aimed at imparting on others the ideology of extremism, belief in its attractiveness or the idea that extremist activities are permissible.”

The bill was adopted in the first reading in September, but its discussion resulted in a heated debate, both in the Committee on State Building and Legislation and at the plenary session. Representatives of the Communist Party faction noted that the proposed “vague wording can lead to law enforcement abuses.” They further expressed their indignation against the current anti-extremist legislation for allowing the punishment of their fellow communists and stated that the amendments would criminalize “mentioning in a positive context such events in Russia’s history as the Decembrist uprising, the February Revolution, the 1991 State Emergency Committee coup attempt or the shelling of the White House in 1993, as well as works of art such as “The Internationale.” The Communist Party of the Russian Federation voted against the bill; the majority of deputies from the SRZP (Spravedlivaya Rossiya – Za pravdu, “A Just Russia – For Truth” Socialist Political Party) abstained, while New People (Novyye lyudi) and the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia did not take part in the vote. The bill was adopted in the first reading only by the votes of United Russia members.

It should be noted that the concept of “ideology of extremism,” which the deputies propose to use in the footnote to Article 280 CC, is not defined by law and can be interpreted broadly. The same is true for the concept of “ideology of terrorism” from Article 2052 CC. However, the very definition of extremist activity (extremism) in the relevant federal law is formulated more expansively and less clearly than the definition of terrorist activity – the factor that could also lead to law enforcement abuses.

We should also add that, under the amendments that came into force in December 2021, materials that contained “defense and (or) justification” of extremist activity are already subject to extrajudicial blocking. Another law adopted in 2022 gave the Prosecutor General's Office the authority to suspend and revoke the registration of media outlets for disseminating such materials.

In 2023, the State Duma adopted, after a number of changes, a bill to change the procedure for recognizing materials as extremist, initiated in January by the Chechen parliament (the president signed it into law in February 2024). According to this law, the courts of the Federation’s constituent entities, rather than district courts, are authorized to consider cases of declaring materials extremist. Copyright holders, publishers, authors of works and (or) translations of materials, if they are known, should be involved in the process. They get the status of interested parties rather than defendants and thus incur no legal costs unless their actions “caused” the claim. If the claim pertains to a publication of a “religious nature,” the court needs to involve an expert “with special knowledge of the relevant religion.” In our opinion, all these provisions of the bill are justified. However, in general, we also believe that problems with the composition and use of the Federal List of Extremist Materials will remain, since the very mechanism for recognizing materials as extremist is ineffective and leads to inappropriate sanctions.

Meanwhile, in June, the president signed a law broadening the scope of Article 20.29 CAO that covers the production and mass distribution of extremist materials. A person became liable not only for distributing materials included on the Federal List of Extremist Materials, as was the case before, but also for materials not yet included on the list, if a court decides that their content meets the definition provided in the law “On Countering Extremist Activity” (or other relevant federal laws that might be adopted in the future).

We also note that Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin signed a decree in March introducing new forensic examination restrictions. Experts from non-state institutions were deprived of the right to conduct linguistic or psycholinguistic forensic examinations in criminal cases related to terrorism and extremism. In our opinion, these innovations might have a negative impact on the adversarial system of justice since the parties lost an opportunity to involve independent experts.

On Control over the Internet

In July, the president approved a law that introduced fines for social networks for evading content moderation. According to another law, in force since February 2021, a social network is defined as a service that includes personal pages of users, advertising aimed at a Russian audience, and daily traffic of over 500 thousand users from Russia. Roskomnadzor maintains the register of social networks. The entities included in it must, upon notifications from Roskomnadzor or based on user complaints and results of their own monitoring, block a wide range of content that is considered illegal in Russia. In mid-July, the deputies suddenly undertook the second reading of the bill on fines, which had seen no movement since April 2018, and promptly adopted it. The amendments introduced administrative liability for the owners of social networks; new articles were added to the CAO with fines ranging from 50 thousand for citizens to eight million for legal entities.

In December, three bills aimed at countering online broadcasts of illegal violent actions or calls for such actions were submitted to the parliament. Primarily, the legislation targets trash-streaming, but they are not the only materials that can fall under the proposed wording.

The first bill introduces a new aggravating circumstance into the Criminal Code (clause “t” of Article 63 Part 1) worded as follows: “committing an intentional crime with its public demonstration, including in the media or on information and telecommunication networks (including the Internet).” The same formula is proposed as a qualifying feature for many intentional violent crimes. At the same time, the proposal allows for imposing an additional punishment under most of the relevant articles of the CC in the form of the loss of the right to hold certain positions or engage in certain activities for a period of up to three years. We consider this bill useful since public displays of violence can – or even should – be considered an aggravating circumstance.

The second bill introduces a ban in the sphere of mass media, namely a new Part 12 of Article 13.15 CAO: “Illegal distribution of information on telecommunication networks, including the Internet, of photos and videos depicting illegal acts committed with cruelty, their consequences, calls to commit such acts for material gain or as hooliganism, as well as actions motivated by racial, national, or religious hatred or enmity, or by hatred or enmity against any social group, unless these actions constitute a criminal offense.” Sanctions for citizens and officials involve fines of up to 700 thousand rubles “with confiscation of equipment used for production of such materials.”

The new part of the article is accompanied by an important note that it does not apply to “works of science, literature, or art that have historical, artistic or cultural value, materials by registered media, as well as photographic and video materials intended for academic or medical purposes, or for study stipulated by federal educational standards and federal educational programs.”

This bill raises some doubts. The word “illegal” at the beginning of the proposed formula is unclear and will inevitably produce controversy and abuse. We believe that public display of violence can only be an administrative offense, if the material in question contains, at the very least, an approval of such violence. If this consideration is taken into account and included in the formula, the word “illegal” becomes unnecessary. Obviously, these changes would mean that the list of exceptions included in the note is unnecessary or needs revision. Currently, the particularly alarming part of the note is the clause stipulating that works of science, literature, and art must possess historical, artistic, or cultural value. It is unclear who and how will determine this value, especially in the context of a rapid trial for an administrative offense.

The two aforementioned bills were adopted in the first reading in January 2024, unlike the third bill from the same package that pertains to the extrajudicial blocking of online materials. The deputies proposed adding a new paragraph to the list of information prohibited for distribution and subject to blocking contained in the Law “On Information”: “photos and videos depicting illegal acts committed with cruelty, their consequences, or calls for the commission of these acts.” The authors of the bill propose blocking such materials by adding them to the Unified Register of Banned Websites. Social networks will also have to identify these materials independently. In addition, such information must be regarded as prohibited for distribution among minors with appropriate legal consequences. We believe that this bill is fundamentally misguided. It lacks reservations and assumes the blocking of all scenes depicting violence. However, the language on blocking in the legislation should not be broader than the language used in the Criminal Codes and the Code of Administrative Offenses. This bill can be amended in the same manner as the second one.

On Non-Profit Organizations

As in recent years, a significant part of the measures to strengthen control over society involved further tightening the legislation on NPOs; the relevant laws were signed by the president in July–August.

An article was added to the current federal law "On Control over the Activities of Persons under Foreign Influence," requiring not only government agencies but also any organizations, office holders, and individuals to take into account the restrictions associated with the "foreign agent" status.

Simultaneously, the Ministry of Justice was empowered to exercise state control not only over "foreign agents" but also over overall compliance with the legislation regulating their activities. Upon request from citizens, organizations, or authorities, the Ministry must conduct unscheduled inspections of any persons or entities that, through their actions or inaction, contribute to violations of the "foreign agents" legislation. The Ministry must then issue warnings with orders to rectify the violations within a month.

In addition, Article 19.5 CAO was amended to include a new clause, Part 42, regarding liability for not complying within the prescribed period with warnings or orders from an agency overseeing the activities of "foreign agents." This new part stipulates fines and, if the offenders acted in their official capacity, their disqualification for up to two years. Liability is imposed if the violations communicated by the Ministry of Justice to a "foreign agent" or another contributing entity are not rectified within a month.

Administrative and criminal liability was introduced for participation in the activities on Russian territory of foreign or international non-governmental non-profit organizations (NGOs) that have no structural subdivisions registered in the country. First, liability for such a violation follows under the new Article 19.34.2. Offenders, already punished twice in the past 12 months or previously convicted under Article 2841 CC (involvement in the activities of an organization recognized as undesirable in Russia), are also liable under Part 1 of the new Article 330.3 CC. Part 2 of the same article established liability for organizers of the work of NGOs that have no registered branches in Russia; it does not require prior administrative sanctions. Thus, involvement in the activities of any foreign or international NGOs that have no branches in Russia entails liability almost as severe as participation in “undesirable organizations.”

In October, a group of deputies and senators introduced in the State Duma a bill on NPOs, which defined the procedure for the withdrawal and expulsion from the list of NPO founders, including religious organizations. The bill also stipulated the case of expulsion from the founders of an NPO of a person whose actions contain signs of extremist activity, according to a court decision. In addition, the bill proposed banning any legal entity included in the list of “undesirable organizations” from being a founder (participant, member) of an NPO or civic association.

Law Enforcement

Sanctions for Anti-Government Statements

Calls for Extremist and Terrorist Activities

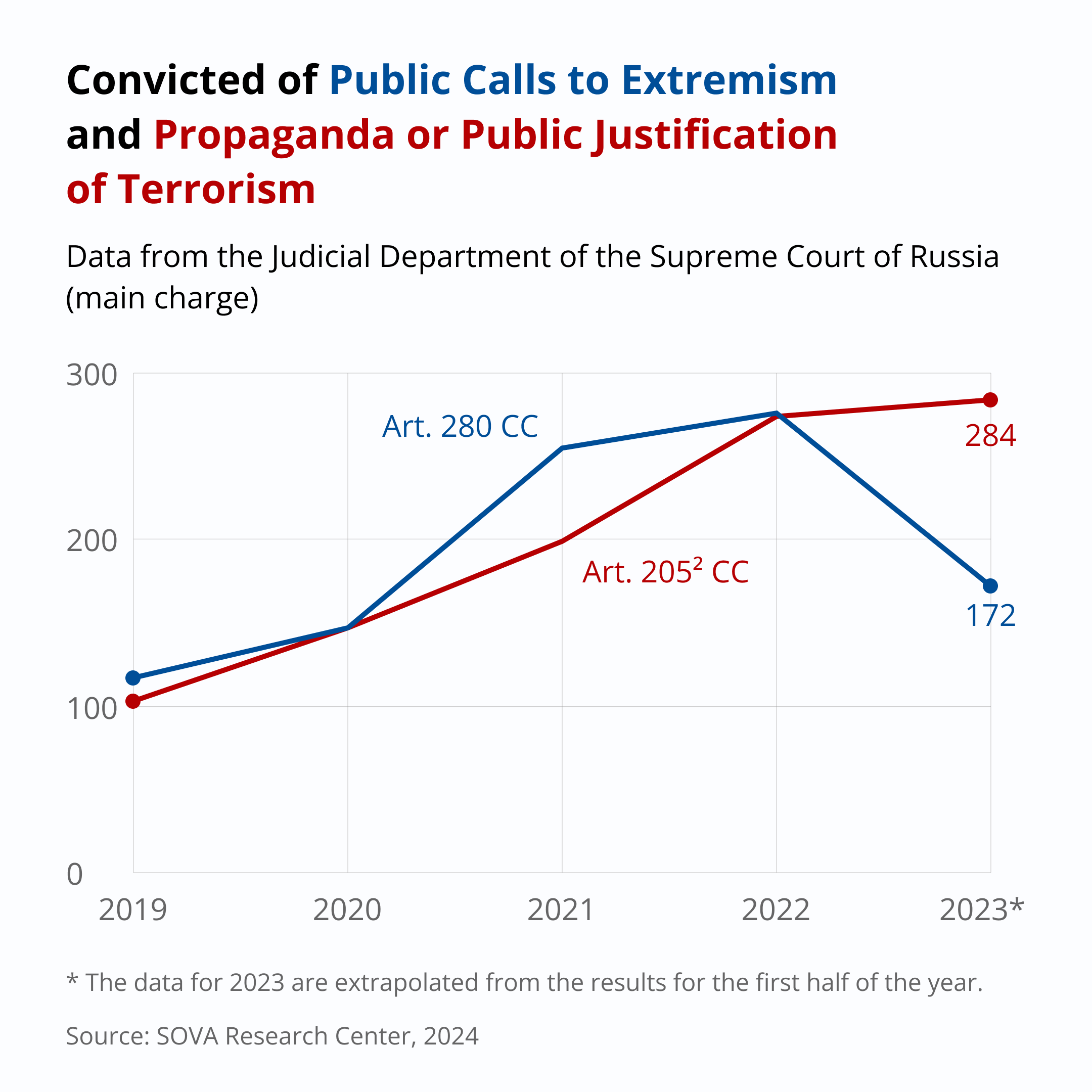

The Supreme Court statistics[5] show the law enforcement dynamics in cases related to calls for extremist activity (Article 280 CC) and calls for terrorism, its justification, and propaganda (Article 2052 CC). The number of people convicted on the main charge under Article 280 CC increased for five years until 2022, when their number reached 276 (this article appeared as an additional charge in the sentences of approximately eighty additional individuals). The number of people convicted on the main charge under Article 2052 CC, has grown steadily over eleven years and reached 274 people in 2022 (an additional charge under this article appeared in the sentences of two people). The Supreme Court has not yet published its statistics for the entire year of 2023, only for its first half. A simple doubling of these figures can only be viewed as a very rough estimate, but based on it, we can assume that the number of those convicted under Article 2052 CC has increased again, while the corresponding number under Article 280 CC has decreased slightly.[6]

The Ministry of Internal Affairs has already published its crime rate for 2023,[7] and it shows the same trend, but only for the cases initiated during the year, not for the verdicts issued.

The number of reported extremist crimes in 2023 totaled 1340 (a drop of 14.4% compared to 2022), but, in 2022 we saw not just an increase but a 48.2% jump. Among the extremist crimes committed in 2023, 367 were classified under Article 280 Part 2 CC as public calls for extremism made on the Internet (25.6% decrease). In 2022, this indicator showed an increase of 8.4%.

In 2023, 2,382 terrorist crimes were registered (a 6.7% increase over 2022), of which 548 (an 11.8% increase) were classified under Article 2052 Part 2 CC as a public justification of terrorism committed on the Internet. For comparison, the overall increase in terrorist crimes in 2022 constituted 4.5%, while the number of crimes under Article 2052 Part 2 CC grew by 55.6%.

Thus, the scope of prosecution under terrorism charges increased in 2023 even more than in 2022, but mainly no longer due to Article 2052 Part 2, although charges under it showed some increase as well. On the other hand, we see fewer cases under anti-extremist articles, including under Article 280 Part 2 CC. This situation is expected to affect the number of convictions later, in 2024–2025, when cases filed by law enforcement agencies in 2023 reach the court.

It is worth reiterating that, as much as we criticize the definitions and norms of Russian legislation related to the concepts of “extremism” and “terrorism,” we believe that there are some instances, in which the state, in accordance with the norms of international law and the Russian Constitution, can legitimately prosecute public statements under criminal procedure as socially dangerous incitement.

In our “Misuse of Anti-Extremism” section on SOVA website, we report only the cases opened for acts that either presented no danger to the state and society, or the danger was clearly insufficient to merit criminal prosecution. However, court decisions in such cases are mostly not published due to the broadly interpreted ban on publishing the texts of judicial acts issued in cases “affecting the security of the state.” The information available from other sources is often insufficient to assess the legitimacy of these decisions.

Meanwhile, law enforcement actions related to the two articles specified above remain not only closed but also particularly repressive. First, there is a accusatorial bias in the proceedings: in principle, public danger should be assessed based not only on the content of the incriminating statement but also on other parameters, including its form, as well as the size and type of the audience or the likelihood that this public statement will lead to grave consequences. However, practice shows that courts very rarely take into account the small likelihood of serious consequences resulting from a statement. Next, a very significant percentage of verdicts under these articles lead to imprisonment, although both articles provide for other punishments as well. The law does not establish clear criteria to determine if incarceration is justified. A court obviously takes into account many circumstances when determining punishment, including the situation in society, which it perceives as tense, and strives to act in line with the legislative and executive branches of government. However, SOVA Center believes that imprisonment, even in case of public calls for violence, is appropriate only when it represents deliberate propaganda of violence (more or less systematic and having at least some chance of implementation) rather than individual emotional outbursts.[8]

More information about sentences under these articles for 2023 is provided in the simultaneously published report by Natalia Yudina.[9]

Prosecutions under Article 2052

We classified only four sentences handed down in 2023 against four people under Article 2052 Part 2 as decidedly inappropriate. All these verdicts pertain to the cases, in which the courts not only failed to assess the extent of the statement’s danger but also classified it incorrectly even from a purely formal standpoint. Two people were fined 300 thousand rubles, while two others were sent to a penal colony.

In particular, the Western District Military Court, at its visiting session in Syktyvkar in December, sentenced left-wing publicist and political scientist Boris Kagarlitsky, the editor-in-chief of Rabkor media to a fine of 800 thousand rubles, which was later reduced to 600 thousand rubles taking into account the fact that the defendant had been in pre-trial detention since July. However, the state prosecutor appealed the verdict and, in February 2024, succeeded in imposing a tougher punishment. The political scientist was sentenced to five years in a penal colony and taken into custody in the courtroom.

Kagarlitsky was punished for the video dedicated to the explosion on the Crimean Bridge that took place on October 8, 2022. The video titled “Explosive Congratulations of Bridgie (Mostik) the Cat: Nervous People and Events, Strikes against Infrastructure” was posted on October 19, 2022, on the Rabkor YouTube channel, as well as on VKontakte and Telegram.

We believe that the verdict is inappropriate, because, in the video, which served as the basis for the prosecution, the political scientist only discussed the circumstances, military-strategic significance, and political consequences of the explosion on the bridge but did not express his approval of it. According to Kagarlitsky and his lawyer, the investigation claims were primarily based on the video's title. However, in our opinion, neither the video nor its title contains any statement “recognizing the ideology and practice of terrorism as correct, in need of support and imitation” (the definition of “justification of terrorism,” according to the note to Article 2052 CC).

The actions of Prokhor Neizhmakov – a refugee from the war zone in Ukraine and another person sentenced to imprisonment – also did not correspond to the article’s provisions. The Western District Military Court sentenced him to three years of imprisonment for messages he sent in November 2022 to the “Vladimir Gang” (Vladimirskaya banda) Telegram chat. Neizhmakov wrote that Russia with its “imperial ambitions” was destroying Ukraine, that due to Vladimir Putin’s policies, he had “no home, education and everything else,” and that “Ukraine will negotiate with Russia only after Putin is overthrown.” In our opinion, the phrase “we will not negotiate with Putin... overthrow him and then let’s go ahead” is too abstract to be considered a call to terrorism – in fact, it says nothing about the methods of “overthrowing.”

In 2023, seven new similar cases against eight people were opened but not tried in courts by the end of the year.

The most notorious of them is the case of the play Finist the Bright Falcon. In May, the creators of the play – director Evgenia Berkovich and the play’s author Svetlana Petriychuk (who is also a screenwriter and a theater teacher) were detained and then placed in pre-trial detention.

The case was based on the video of the Finist the Bright Falcon reading at the Lyubimovka Young Drama Festival, published online in 2019. The corresponding performance was staged by the SOSO Daughters Theater project in 2021. The play tells the story of women who were recruited into militant Islamic organizations recognized as terrorist. The authors raise the question of what exactly allows recruiters – often also women, who conduct correspondence, including love letters, posing as men – to successfully deceive their correspondents, convincing them to get married online and then reunite with their virtual spouses in Syria. The play is partially documentary as it draws inspiration from various sources, including court decisions under Article 208 CC (regarding participation in illegal armed groups) and messages from peaceful Islamic educational websites. It weaves together these documentary textual elements with fragments from Russian folk tales and scenes from well-known Walt Disney Studio cartoons.

In our opinion, the play contained no elements of propaganda or endorsement of the ideology of ISIS or militant Islamism. On the contrary, the play clearly aims to combat the ideologies and actions of terrorists. Moreover, the performance also received the national Golden Mask award in 2022 and had a successful three-year theater run. The sudden keen interest in this play, clearly unfounded law enforcement claims, and the fact that the defendants have been subject to the most severe measure of restraint can likely be explained by the public activities of the director. Evgenia Berkovich is a well-known blogger and a poet renowned for her series of anti-war poems.

The prosecution initially based its arguments on the expert opinion compiled by religious scholar Roman Silantyev, a notorious fighter against “sects” and “non-traditional Islam,” and his colleagues at the Moscow State Linguistic University. The head of the Human Rights Center of the World Russian People's Council, Silantyev invented his own field of science, “destructology,” which he now applies to a wide range of social phenomena including various banned associations. According to the expert opinion, the play contains “signs of destructive ideologies,” namely the ideologies of ISIS, jihadism, and caliphism, as well as “signs of the destructive subculture of Russian neophyte wives of terrorists and extremists.” In addition, the experts found elements of the “radical feminist ideology” in the materials of the performance. After the text of the examination was made public and caused predictable public outrage, a new examination was ordered.

The next expertise was conducted by Svetlana Mochalova, an expert at the FSB department for the Sverdlovsk Region, whose conclusions have been repeatedly used as evidence of guilt in “extremist” cases, in particular, in cases against Muslims or cases on recognizing Islamic materials as extremist. Mochalova felt that the playwright and director specifically created a “romantic image of a terrorist” in the play to make him “interesting and attractive to girls and women,” in contrast to Russian men, whom the play’s female characters characterize negatively. Mochalova’s expert opinion offered exceedingly dubious interpretations of Islamic traditions, ignored the general and quite obvious idea of the play, and made not only linguistic but also legal conclusions, thus stepping outside her area of expertise.

The final version of the charges against Berkovich and Petriychuk was brought only in late February 2024. In March, their pre-trial detention was extended once again.

Prosecutions under Article 280

We classified three sentences handed down under this article in 2023 as inappropriate; all three offenders were sentenced to imprisonment.

The case of amateur military graves finder Oleg Belousov under Article 280 CC was based on three comments in the “St. Petersburg Diggers” (Piterskiye Kopateli) VKontakte community that criticized the actions of the Russian armed forces in Ukraine. In one of them, Belousov called Vladimir Putin a war criminal; in the second one, he spoke of Putin’s involvement in the murder of civilians in Ukraine; in the third comment, as part of a dispute with another social network user who accused Ukrainians of trying to “ban the Russian language,” Belousov rhetorically asked whether the appropriate response required the destruction of Russian-speaking cities of Ukraine.

Considering the first two comments, the court relied on the provision of the Law on Countering Extremist Activity, according to which publicly falsely accusing state officials of extremism constitutes extremist activity. We believe that the law should have no place for such a provision. False accusations of any crime brought by one person against another, regardless of the social status of either party, can be reviewed in court as a libel case. It should also be noted that Article 280 CC punishes calls for extremist activity, but Belousov's statement about the president being a criminal contained no appeals. Law enforcement agencies and the court interpreted the third comment, about Russian-speaking cities, as a call for the destruction of Kharkiv and Mariupol completely ignoring its context. Under the aggregation of Article 280 Part 2 CC and paragraph “e” of Article 207.3 Part 2 CC about “fakes about the army” (we write more about this norm below), the court sentenced Belousov to five and a half years in a minimum-security penal colony.

We classified as inappropriate charges under Article 280 CC filed against four more people.

A very well-known figure was among those inappropriately charged under this article. Strelkov (Girkin) – a popular military blogger and former Minister of Defense of the Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) was arrested in Moscow in July. Strelkov, the leader of the “Angry Patriots’ Club,” was one of the most ardent critics of the way the special military operation has been conducted, despite viewing it as necessary and even stating that its goals have been set too narrowly. The criminal case against Strelkov was based on his Telegram post dated May 22, 2022. The post, read by over 432 thousand people, discussed the non-payment of salaries to soldiers of the 105th and 107th regiments of the DPR Armed Forces. Strelkov wrote that an “execution is not enough” to punish those responsible for such situations. We believe that Strelkov, in this post, merely expressed his emotions. He was talking figuratively, and it is unlikely that his words could be regarded as a call to shoot people, even taking his combat experience and wide audience into account.[10]

Incitement of Hatred

In 2023, we recorded 58 instances of inappropriate charges under Article 20.3.1 CAO for incitement to hatred or enmity or for humiliation of human dignity based on belonging to a particular group (a year earlier we noted 65 such cases). 56 individuals faced punishment. A fine was imposed in 47 cases (in most cases of 10 thousand rubles), and arrest in nine. Two cases were closed.

In the vast majority of cases, inappropriate sanctions targeted internet users for their critical statements against the authorities and law enforcement agencies.

We classify sanctions for crudely worded critical statements about government officials as inappropriate.[11] In our view, unlike members of groups based on ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation gender identity, homelessness, or disability, people in positions of power do not have a vulnerability that requires special protection from expressions of hatred. We would like to reiterate that we advocate excluding the nebulous term “social group” from the norms on incitement to hatred due to its vagueness, which leads to an expansive interpretation.

In more than a third of all cases, the charges under Article 20.3.1 CAO were based on harsh statements about representatives of law enforcement agencies that contained no calls for violence. Sanctions were also imposed following immoderate remarks against officials, the military, representatives of the ruling party, the authorities in general, and the president personally; this speech was also regarded as inciting social hatred. The critics expressed dissatisfaction with the armed actions against Ukraine or addressed police brutality and abuses perpetuated by local officials.

Political or social criticism aimed at Russian citizens (expressed most frequently by other Russian citizens) for supporting the regime’s policies (especially toward Ukraine) or for passivity, cowardice, laziness, etc. also often incurred sanctions, since law enforcement agencies and courts interpreted it as inciting national hatred or hatred towards a social group (for example, towards groups defined as “the special military operation supporters,” “the citizens of Russia,” etc.)

In 2023, we recorded three inappropriate verdicts against eight people under Article 282 CC on incitement to hatred with aggravating circumstances.

In particular, a verdict in the Mayakovsky Poetry Readings case was pronounced in Moscow in December. The court sentenced Artyom Kamardin to seven years in a minimum-security penal colony, and Yegor Shtovba – to five and a half years. They were found guilty of inciting hatred by an organized group under paragraph “c” Article 282 Part 2 CC and of calls for anti-state activities, also as part of an organized group, under Article 2804 Part 3 CC. Earlier, the third defendant in the case, Nikolai Daineko, was sentenced to four years in a minimum-security penal colony; he entered a pre-trial agreement with the investigation. The poets faced criminal responsibility after the readings that took place on September 25, 2023 at Triumfalnaya Square (formerly Mayakovsky Square) in Moscow. Participants called them “anti-mobilization readings.” During the readings, among his other statements, Kamardin characterized the Donbas militia as terrorists and recited two poems. According to the investigation, Shtovba and Daineko repeated the words of one of the poems, “Kill me, Militiaman!” Law enforcement agencies concluded that the statements contained signs of inciting hatred or enmity against volunteer armed groups of the DPR/LPR and called for violence against them and their families. In our opinion, Kamardin's poem could be characterized as provocative, and seen as offensive, but it contained no incitement to violence. The charge under Article 2804 was related to the fact that law enforcement agencies found statements about the need to “resist” partial mobilization in the post on the Mayakovsky Poetry Readings Telegram channel announcing the event. However, Kamardin, Shtovba, and Daineko did not call for the commission of crimes. They wrote about a failure to report to a military enlistment office upon receiving a mobilization summons, which constitutes an administrative offense. Accordingly, we regard their prosecution under the criminal article as inappropriate.[12]

Six out of the seven remaining cases in 2023, which were not concluded before the end of the year, were opened under Article 282 Part 1 CC. This article is applied in cases of repeated charges for inciting hatred within a year. One case was initiated under Part 2 due to aggravating circumstances.

Thus, in October, a criminal case was opened in the Kemerovo Region under Article 282 Part 1 CC against Lenard Valeev, a resident of Prokopyevsk, The case was based on a comment left by Valeev on the “The Lower Depths” (Na Dne) VKontakte public page under a post about a criminal case opened in connection with the Wagner Group’s armed rebellion. Valeev wrote that “Prigozhin disturbed the Russian chicken coop, in which everyone sits on their allotted roost,” but nothing came out of it other than noise, since “in this semi-state made of plywood and cardboard” there are no citizens, “only fakes and the cowardly population, who can’t do a damn thing.” The experts who examined the comment concluded that “the post contains statements that incite hatred, enmity and humiliate the human dignity of citizens,” “residents of the Russian Federation.” Previously, Valeev had faced administrative sanctions for his comment under a video in a certain newsgroup, which contained a negative assessment of a social group identified “on the basis of being residents of Russia’s regions.”

Displaying Banned Symbols

The Judicial Department of the Supreme Court, in its statistics

on the application of the CAO for the first half of 2023, as in 2022, for an unknown

reason combined Article 20.3 CAO (propaganda and display of banned symbols) in the

same group with Article 20.3.1 CAO on incitement to hatred. In the entire 2022,

sanctions under these two articles were imposed 5,720 times, and in the first half

of 2023, their number reached 2,617. So, the numbers remain approximately the same

as last year even though, over the preceding years, the application of Article 20.3

had grown rapidly.

As usual, we know the details of the corresponding administrative cases and can assess their appropriateness only for some of these incidents. We view sanctions under Article 20.3 CAO for the display of symbols with no intent to promote Nazism or extremist ideology as inappropriate. We noted more cases opened inappropriately in 2023 than in 2022. According to our information, at least 147 people faced charges without proper justification (we recorded 120 such cases in 2022).

Courts imposed a fine in 99 cases, administrative arrest in 41 cases, a ban on “visiting the venues of official sports competitions on the days of their holding” in one case, and in one case, the punishment is unknown. Two cases were dismissed and one person was released from liability due to age.

Most cases involve the display of a prohibited symbol as part of a political discussion or in a neutral context that is for some reason perceived as extremist by law enforcement agencies.

As in previous years, public displays of Nazi symbols often took place not to promote Nazism, but as a means of visually criticizing political opponents – in most cases the Russian authorities. We counted 35 such episodes. Mostly, the images involved the swastika superimposed on a photo of the president or Russian state symbols, or the swastika compared with the symbols of the special military operation.

In 31 cases, the offense consisted of the use of the slogan “Glory to Ukraine” (in any form – oral or written, offline and online), or images with the Ukrainian national emblem, the trident. Both are often interpreted by law enforcement agencies and courts as attributes of banned Ukrainian nationalist organizations, even though the slogan has been ubiquitous in Ukraine in recent years and has been an official greeting in the Ukrainian army and police since 2018, and the trident is the central element of Ukraine’s state emblem. This approach provides law enforcement officers with yet another way to use sanctions against supporters of Ukraine.

According to our records, 25 of the cases involved the display of a white-blue-white flag (in images published on social networks, as well as in the form of ribbons, stickers, balloons, etc.) Russian law enforcement agencies and courts view it as the emblem of the Freedom of Russia Legion (recognized as a terrorist organization), although the Legion’s version of the flag has an image of a fist superimposed on it. The white-blue-white flag as such appeared among Russian emigrants in late February 2022, before the creation of the legion, and is still widely used as a symbol of opposition to the Russian authorities, including without any connection with the legion. Thus, people are often punished inappropriately.

In addition, many convicted offenders apparently did not display the white-blue-white flag intentionally but became victims of provocation. It is possible that, in 2023, activists in some regions pasted white-blue-white stickers on license plates of parked cars or covered up the red stripe on Russian flags. There were at least 13 such cases. A resident of Birobidzhan fined for this offense explained in court that he had recently bought a car with state license plates, paid no attention to the colors of the flags, and had never heard of the Freedom of Russia Legion. However, the court found that “the owner of the car did not show the necessary diligence required of him to know what was displayed on his car,” while “information about the symbols of this organization is available on the Internet.”

Another significant group consisted of 16 people who faced sanctions for demonstrating the symbols of Alexei Navalny’s structures. See below for more information on them.

We know of five cases initiated without proper grounds in 2023 under Article 2824 CC on repeated demonstration of prohibited symbols. Two of them were related to the demonstration of the white-blue-white flag on Telegram; three more were related to the repeated demonstration of Nazi symbols not aimed at promoting Nazism. Two of the five cases resulted in convictions in 2023.

There was one guilty verdict. Dmitry Lyalyaev from Kireyevsk of the Tula Region was sentenced to two years in an open prison under Article 2824 Part 1 and Article 280 Part 2 CC for multiple publications of images of Vladimir Putin with Nazi symbols and AUE symbols.

The other verdict was an acquittal. A “Citizen of the USSR,” Sanan Ulanov from Elista, published materials on VKontakte intended to prove that the Vlasov Army had used the Russian tricolor; these materials featured military personnel wearing the Russian Liberation Army chevrons. Ulanov was first fined for his post with a similar image back in 2020. Considering himself a “citizen of the USSR” and not recognizing the legitimacy of the Russian Federation’s authorities, he did not pay the fine and, thus, continued to be considered a convicted offender under Article 20.3 Part 1 CAO. Thus, he faced criminal charges after posting on his VKontakte page, on two separate occasions, a link to a YouTube video of the song “Take the Vlasov banner off the Golden-Domed Kremlin!” that contained Nazi symbols. In September 2023, the city court sentenced Ulanov to two years in a settlement colony. In early December, the Supreme Court of Kalmykia considered an appeal against the verdict. The court rightly pointed out that the ban on displaying symbols does not apply to statements that formed a negative attitude to the ideology of Nazism and extremism and contained no signs of propaganda or justification of Nazi and extremist ideology. The court noted that the video disseminated by Ulanov was not intended to form a positive attitude toward Nazism, nor did it insult the memory of the Great Patriotic War victims. The verdict was overturned, and Ulanov was completely acquitted. The decision was made posthumously, as, according to the Federal Penitentiary Service, the defendant committed suicide in a pre-trial detention center.

Discrediting the Military and Government Agencies

We view punishment for disseminating knowingly false information

about the actions of Russian military and government agencies abroad or discrediting

them as an inappropriate restriction on the right to freedom of speech. In our

opinion, the only reason for imposing these sanctions

was the desire of the authorities to limit the dissemination of independent information

about events in Ukraine and criticism of the actions of the Russian government and

military forces.

According to the data of the State Automated System “Pravosudie” collected by the OVD-Info project, 2830 cases under Article 20.3.3 CAO on discrediting the use of the armed forces and government agencies, were submitted to Russian courts for review in 2023 (compared to 5518 in 2022, according to the data provided by the Mediazona portal in the second half of December 2022). OVD-Info attributes the almost 50% drop in the number of claims under Article 20.3.3 CAO in 2023 primarily to the absence of mass anti-war actions, for which people were punished in 2022. According to OVD-Info, the greatest number of cases were opened in Crimea, followed by Moscow, St. Petersburg, Krasnodar Krai, and the Sverdlovsk Region.[13] The courts reviewed 2,707 out of the 2,830 cases and punished 2,113 people (according to the Supreme Court data, 4,440 people were punished in 2022).

Most often, people face sanctions for their anti-war statements made online, but also for offline statements in front of audiences of varying sizes, for displaying posters, distributing printed propaganda materials, etc.

While in 2022, the courts managed to pass only three sentences against three people under Article 2803 CC on repeated discrediting of the actions of the Russian army and officials abroad, at least 67 people were found guilty under this article in 2023.[14] In addition, in one case the court terminated the proceedings due to the defendant’s death. Of the 67 convicted offenders, 63 verdicts were, in our opinion, clearly inappropriate; in four other cases, the charges included violence, dangerous vandalism, or threats of violence. One of the 63 had his conviction overturned in 2024; the case was remanded for a new trial.

Of the 62 wrongfully convicted individuals, 11 people were sentenced to imprisonment, two to compulsory labor, seven people received suspended sentences, 38 people were sentenced to fines from 100 to 500 thousand rubles, and we do not know the type of punishment imposed in the four remaining cases.

One of the most high-profile cases of repeated discrediting of the army was the case of Alexei Moskalyov, a resident of Yefremov in the Tula Region. In April 2022, after a scandal at his daughter’s school because of her anti-war drawing, Moskalyov was fined under Article 20.3.3 Part 1 CAO for his posts on Odnoklassniki about the rape of Ukrainian women by Russian soldiers. The criminal charges were based on other posts he made on the same social network, in particular, regarding the events in Bucha and the death of prisoners of war in Yelenovka. After a search and interrogation by the FSB, Moskalyov and his daughter, whom he was raising alone, left the city, and he was put on the wanted list. In early March 2023, Moskalyov was detained and placed under house arrest the next day since he had failed to appear on time when ordered by the investigator. Meanwhile, his 13-year-old daughter was placed in a social rehabilitation center for minors. She remained there until her mother, who had not taken part in her upbringing for several years, took her out. On the eve of the verdict, Moskalyov escaped from under arrest and was detained in Minsk two days later. On March 28, the Yefremov Interdistrict Court of the Tula Region sentenced him to two years of imprisonment. In early 2024, the regional court reduced his term by two months.

Another high-profile case under Article 2803 Part 1 CC was the case of Oleg Orlov, a co-chairman of the HRDC “Memorial.” The case against Orlov was based on his Facebook post made in November 2022. The post contained the Russian text of Orlov’s article “They Wanted Fascism. They Got It,” previously published in French by Mediapart. On October 11, 2023, the Golovinsky District Court of Moscow sentenced Orlov to a fine of 150 thousand rubles. The prosecution appealed this verdict, demanding a tougher punishment, and then asked the appellate instance to return the case to the prosecutors altogether, so that the investigation could establish a motive for the crime. The court granted this request overturning the sentence imposed on Orlov. The new version of the indictment added aggravating circumstances: according to investigators, Orlov committed a crime motivated by “ideological enmity towards traditional spiritual, moral and patriotic values,” as well as hatred of the social group “military personnel.” In late February 2024, the same Golovinsky District Court sentenced Orlov to two and a half years of imprisonment. The wording of the charge directly indicated that Orlov was punished for speaking out against the official ideology.

In addition to those convicted in 2023 under Article 2803 CC, we know of 59 people who were wrongfully prosecuted under this article but not yet sentenced by the end of the year (we knew of approximately 40 in 2022). Two of them died, and one case was dropped; thus, at least 56 people still face charges.

Spreading “Fake News” about the Special Military Operation Motivated by Hatred

We believe that allegations

of defamation should be subject to civil, rather

than criminal, proceedings. Moreover, regarding Article 2073 CC, it

is not clear to us why the dissemination of false information about the

activities of military personnel or officials requires a separate legal norm

with disproportionately severe sanctions.[15]

SOVA Center includes in its monitoring only libel charges that are filed with a hate motive as an aggravating circumstance. In our view, when using Article 2073, the motive of ideological and political hatred is applied inappropriately. People who publish information about the military operations in Ukraine that differs from the official line obviously tend to ideologically and politically disagree with the course pursued by the authorities – that is, in most of these cases, their acts are a form of political criticism.[16] As for social hatred, groups such as military personnel or officials do not require protection from its manifestations being well-protected by other legal norms. However, we do not classify the cases under Article 2073 CC as inappropriate if the relevant statements contain obvious signs of inciting national hatred or calls for violence.

According to our information, at least 52 verdicts against 54 people were issued under clause “e” of Article 2073 Part 2 CC (disseminating knowingly false information about the actions of the armed forces motivated by hatred) in 2023, but one of them was overturned and sent for a re-trial. Five more people were released from criminal liability and referred for compulsory treatment.

Of the 51 guilty verdicts that remain in force, we consider 47 sentences to 49 individuals to be inappropriate. 44 offenders were sentenced to real terms of incarceration, mostly from five to ten years, often with additional sanctions, such as several-year bans on posting information online. Two defendants received suspended sentences, one was fined 1.8 million rubles, and we do not know what punishment was imposed on the remaining two.[17]

It should be noted that 17 sentences against 18 people were pronounced in absentia, mainly those targeting well-known opponents of the regime living abroad (including, for example, publicist Alexander Nevzorov, blogger Maxim Kats, media managers Nika Belotserkovskaya and Ilya Krasilschik, activist Ruslan Leviev, journalist Michael Nacke, writer Dmitry Glukhovsky, and others).

However, those who ended up behind bars were in the majority. For example, activist Olga Smirnova from St. Petersburg received six years in a minimum-security penal colony for publishing seven posts in the “Democratic St. Petersburg – Peaceful Resistance” group on VKontakte in March 2022. They were dedicated to the destruction in Ukrainian cities, victims in Zaporizhzhia, Kharkiv, Kyiv, and Izyum, the fire at the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, damage to the Babi Yar Holocaust memorial, and deaths of Mariupol residents. Blogger Alexander Nozdrinov from Novokubansk of Krasnodar Krai was sentenced to eight and a half years in a penal colony under paragraphs “e” and “d” (for financial gain) of Article 2073 Part 2 CC. He was found guilty of posting on his Telegram channel a photograph of a destroyed Ukrainian city and a comment underneath it. The blogger had allegedly received a thousand rubles for the post.

The charge of disseminating “fake news” also appeared in the case of politician and journalist Vladimir Kara-Murza sentenced to 25 years in a maximum-security penal colony and several additional punishments through the partial aggregation of sentences imposed under three articles – paragraph “e” of Article 2073 Part 2 CC (seven years), Article 2841 Part 1 CC on the activities of an “undesirable organization” (three years), and Article 275 CC on high treason (18 years). The case for spreading “fakes about the army” was based on Kara-Murza's speech in the Arizona House of Representatives in the United States on March 15, 2022, in which he said that Russian troops were committing war crimes on the territory of Ukraine.

Article 2073 CC has become an instrument of intimidation for the Russian authorities to limit the dissemination of independent information about the military operation in Ukraine. Hence the demonstrative initiation of criminal cases against well-known figures, and severe sanctions against ordinary citizens.

We know of at least 66 people charged under paragraph “e” of Article 2073 Part 2 CC in 2023, whose cases were not yet tried in courts by the end of the year. Once again, this group includes many prominent figures, who have left Russia (mostly journalists, political scientists, and public activists), as well as several well-known Ukrainians, but also numerous ordinary citizens who resided in Russia and were taken into custody. A separate group of 15 defendants in the case of the Vesna movement face charges under several criminal articles, including this one. For comparison, by the end of 2022 (Article 2073 was added to the Criminal Code in March), we also knew of more than 60 people charged with distributing “military fakes” motivated by hatred; courts managed to issue sentences against another nine defendants before the year ended.

Other Anti-Government Statements

According to our data,

at least 28 cases were opened in 2023 under Article 20.1 Parts 3–5 CAO for disseminating

information that expresses disrespect for the state and society in an indecent form

on the Internet. There were at least 22 such cases a year earlier, at least 37 in

2021, at least 30 in 2020, and 56 in 2019. In 2023, fines were imposed in 27 cases

(from 30 to 80 thousand rubles under Article 20.1 Part 1 CAO and from 100 to 250

thousand under Parts 4–5), and one case was dismissed. Almost all charges were

related to disrespect toward the president, occasionally – disrespect toward other high-ranking

officials, the authorities in general, and state symbols.

The majority of cases known to us took place in Crimea. This can be attributed to the activity of the “Crimean SMERSH” Telegram channel, which is owned by local activist Alexander Talipov. He actively monitors the social networks of Crimean residents and submits statements to law enforcement agencies. For instance, Crimean Olga Dibrova was fined 80 thousand rubles under Article 20.1 Part 3 CAO. She was detained after a video was published on “Crimean SMERSH,” which showed her using obscene language directed at President Putin when her electricity was turned off.

For the first half of 2023, the Judicial Department of the Supreme Court reported a total of 16 individuals punished under Article 20.3.2 CAO (calling for violation of the territorial integrity of Russia) and Article 20.3.4 CAO (calling for sanctions against Russia, its organizations and citizens), but we have no information about anyone facing sanctions under Article 20.3.4 CAO. According to the data provided by the State Automated System “Pravosudie,” no cases were opened on repeated calls for sanctions under Article 2842 CC. As for Article 20.3.2 CAO, we know of only five such cases. Three of them were not related to calls for any violent separatist actions, so we regard these sanctions for discussions on territorial issues as inappropriate (we also recorded three such cases in 2022). All three inappropriately charged defendants faced fines: one of 30 thousand rubles, and two – of 70 thousand rubles. The issue under discussion in all cases pertained to territories seized from Ukraine.

According to the data provided by the State Automated System “Pravosudie,” there were no cases of charges under Article 2801 CC for repeated calls for violation of the territorial integrity of Russia in 2023. There were no such cases in 2022 either.

Vandalism Motivated by Hatred

We know of 11 clearly inappropriate

verdicts under Article 214 Part 2 CC (vandalism motivated by political or ideological

hatred) issued in 2023 against 15 people for protests against the special military

operation (in 2022, we recorded 12 such sentences against 13 people, but two sentences

were subsequently overturned). Seven people were sentenced to restriction of freedom,

four to imprisonment (for all four, Article 214 CC was not the only charge

against them), and in one case we have no information about the punishment imposed.

Two more cases were dismissed by the court due to the expiry of the limitation

period, and one person was referred for compulsory treatment and released from liability.

Similarly to the preceding year, most of the offenses involved writing anti-war or pro-Ukrainian slogans in public places or inflicting damage on posters dedicated to the special military operation. We include in our monitoring only the cases, in which law enforcement agencies charge defendants with vandalism motivated by ideological or political hatred, although the presence or absence of the hate motive in such cases obviously depends solely on the discretion of specific law enforcement officers, and not on the actual circumstances of an incident. We see no need to prosecute people for vandalism motivated by political or ideological hatred. In our opinion, in most cases, such actions represent a form of political criticism. We also believe, as we wrote above, that the motive of political or ideological hatred should be used as an aggravating circumstance only in articles on violent crimes.

In addition, when property damage is minor, in our opinion, cases under Article 214 should be terminated for insignificance or with the imposition of a court fine. For those cases where the damage is relatively small, it might be helpful to introduce an article similar to Article 7.17 CAO covering the destruction or damage of other people's property or to clarify the existing article by adding vandalism that did not cause major damage.

One of the offenders sentenced in 2023 was Sergei Khozyaykin from Belovo of the Kemerovo Region, sentenced to six months of restricted freedom for throwing the shells from two eggs filled with red enamel at a banner with the image of Vladimir Putin “thus imitating blood as a symbol of bloodshed and violence.” The court found that Khozyaykin had acted “with the intent of creating false associations and inciting hatred and enmity in an indefinitely wide group of people.”

Meanwhile, Alexei Arbuzenko from Togliatti, who, together with his teenage son “motivated by hooliganism” threw paint on banners depicting Russian military personnel and covered them with certain “cynical slogans,” was charged not only under Article 214 Part 2 but also under Article 2803 Part 2 and Article 150 Part 4 CC (involvement of a minor in a criminal group or the commission of a crime motivated by political, ideological, racial, national or religious hatred). The court sentenced him to six years in a minimal-security penal colony.

We have information about 11 other similar cases initiated under Article 214 Part 2 CC in 2023 against 12 people that either did not go to trial by the end of the year, or of which we do not know the outcome. Once again, the charges are based on graffiti and damage to banners. The defendants in criminal cases, for example, include a 62-year-old woman, resident of Balaklava, who painted Ukrainian flags on the building walls, bus stops, benches, lamp posts, park fences, and town squares as well as famous Moscow graffiti artist Filipp Kozlov (Philippenzo). The case against Kozlov was based on his work “Izrossilovanie” [a wordplay based on the words “rape” and “Russia] – a graffiti under the Elektrozavodsky Bridge on the Yauza embankment depicting this caption and the Russian coat of arms. The artist has left Russia and was placed on the wanted list.

We also note that in 2023, the court issued a two-year suspended sentence followed by a two-year probationary period to retiree Irina Tsybaneva from St. Petersburg, whose case we mentioned in our 2022 report. The court found her guilty of desecrating burial places with the motive of political hatred (paragraph “b” of Article 244 Part 2 CC). Tsybaneva left a note on the grave of Vladimir Putin's parents at the Serafimovskoye Cemetery, in which she wished their son, “who has caused so much pain and trouble,” dead. In our opinion, Tsybaneva did not cause any harm to the grave.

Hooliganism Motivated by Hatred

We classify as inappropriate the cases under

paragraph “b” of Article 213 Part 2 CC (hooliganism motivated by political,

ideological, or social hatred) that were initiated against participants in

public actions that, in our opinion, should not be regarded as gross violations

of public order and disrespect for society. On the contrary, the purpose of such actions was obviously to draw

public attention to important social and political issues. Besides, here, as in

the cases of vandalism (see above), we consider the motive of ideological or

political hatred unnecessary, since these are not violent crimes but a form of

socio-political expression.

At least two criminal cases in this category were opened in 2023[18] (we recorded three such verdicts against four people in 2022; one more case was likely closed).

Konstantin Kochanov, an electrician from Moscow, was arrested in Moscow in May. On the night of May 9, he painted at least three red crosses on the pavement near houses on Bolshoy Kozlovsky Lane and Nizhnyaya Krasnoselskaya Street. Later, photographs of the graffiti were posted on Ukrainian Telegram channels as allegedly special marks to be used for a drone attack on the capital. According to law enforcement officers, Kochanov’s actions expressed “his disagreement with Russia’s ongoing special military operation in Ukraine,” and he “performed public actions that created a credible threat to the state security and a threat of harm to the life and health of citizens.” At first, the Ministry of Internal Affairs did not want to initiate a case; the Telegram channel “War on Fakes,” affiliated with the law enforcement agencies, wrote that the marks indicated geodesical points. Obviously, the signs painted by Kochanov had no practical meaning and did not lead to a gross violation of public order. Later he was also charged under Article 214 Part 1 CC, even though he painted crosses on the pavement rather than buildings or structures. Despite his serious illness, Kochanov spent about six months in pre-trial detention before his preventive measure was changed.

Artyom Lazarenko faced charges in September after he “took off all his clothes” and “began to demonstrate his naked body” in front of the FSB building. The investigation decided that he grossly violated public order and was acting out of hatred towards law enforcement officers. However, Lazarenko acted at night and therefore did not disrupt citizens’ work or leisure, or the work of institutions. In our opinion, the administrative charges under Article 20.1 CAO (disorderly conduct) would have sufficed.[19]

Involvement in Banned Oppositional Organizations

Persecution of Alexei Navalny and His Supporters

Throughout 2023, the authorities continued to persecute

Alexei Navalny and his supporters. As

we reported earlier, the structures associated with

Navalny – the Alexei Navalny Headquarters, the Anti-Corruption

Foundation (FBK), and the Citizens' Rights Defense Fund (FZPG) – were