Summary

Criminal prosecution : For public statements : For participation in extremist groups and banned organizations

The Federal List of Extremist Materials

Organizations banned for being extremist

Other administrative measures : Prosecution for administrative offenses : Blocking on the internet

Crime and punishment statistics

Summary

A definite shift has occurred in the scope of criminal law enforcement since early 2018. According to the monitoring of SOVA Center,[1]for the first time in many years the number of criminal convictions for public “extremist statements” (the promotion of hate, calls for extremist or terrorist activities, etc.) started to drop, even though the total number of these convictions still exceeds the number of convictions for all other “extremist crimes.” Clearly, the growing public outcry over the scale and quality of this type of criminal law enforcement has played a role, and discussions about reforming anti-extremist laws, which began in the summer, have accelerated the events.

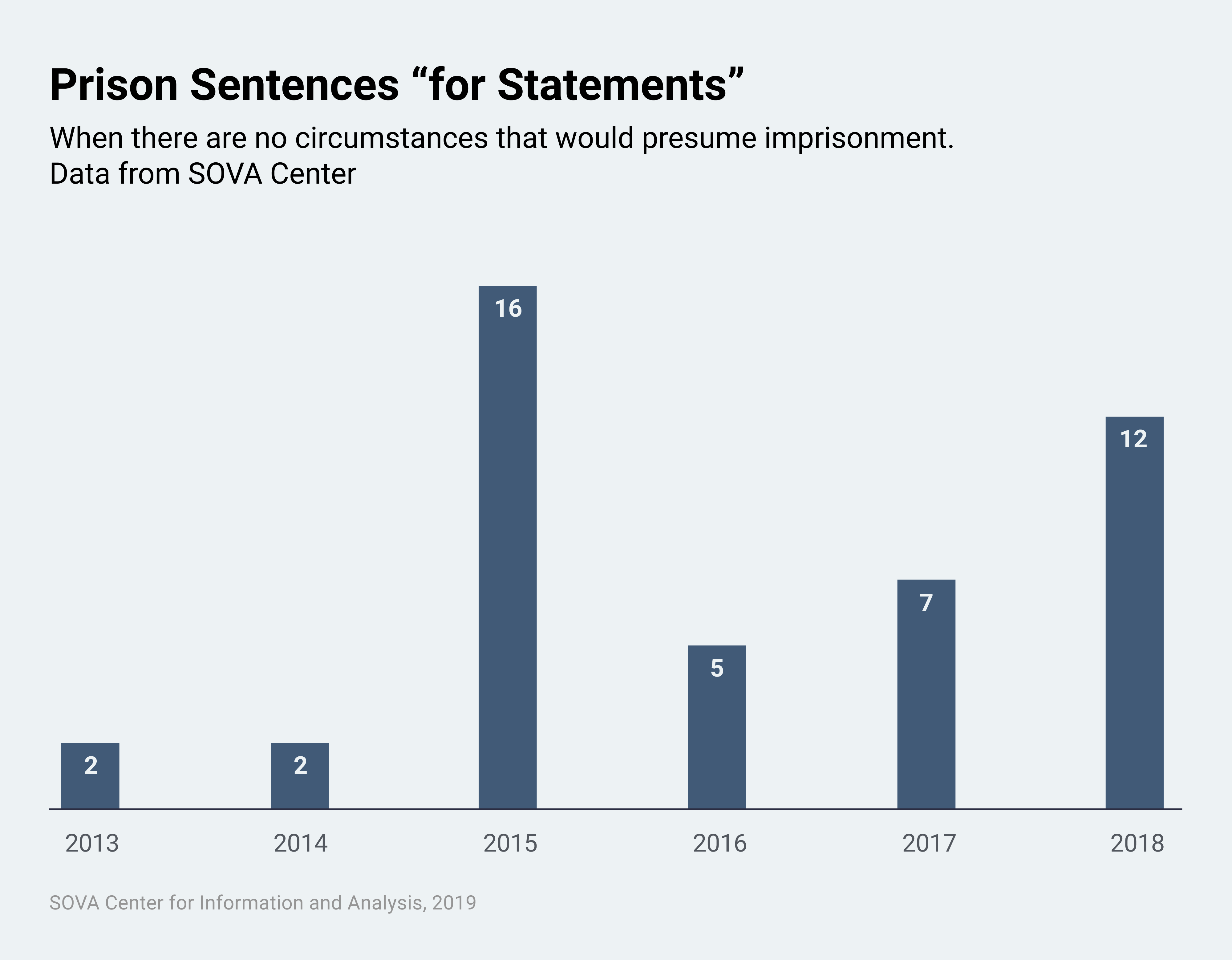

However, the quality of this law enforcement continues to be a cause for concern. Punishments became harsher, and the number of people sentenced to prison terms “only for words” without formal or informal aggravating circumstances has again increased. At the same time, punishments of figures popular among the ultra-right did not involve prison terms.

Criminal prosecution of people for participation in extremist organizations remained at the same level as 2017. Notably, if we exclude clearly unjustified prosecutions, all the convictions known to us were connected with membership in Ukraine’s Right Sector or the pro-Ukrainian Misanthropic Division. The number of convictions for violent crimes motivated by hate also fell, but this was the topic of our previous report.[2]

While criminal prosecution is declining, the number of administrative convictions under anti-extremist articles of the Code of Administrative Offenses (CAO) has grown. In addition, we have observed a stable number of pointless and harsh bans on internet use and the confiscation of expensive “tools of crime” such as laptop computers, tablets, and smartphones in criminal and administrative cases.

Along with the Federal List of Extremist Materials, two other lists related to blocking access to “extremist” content on the internet – registers of judicial and extrajudicial blocking – are swelling, and it's the extrajudicial one that's growing the fastest.

In this way, even though we have seen an improvement in the practice of criminal prosecution for statements, the problem of the arbitrary application of anti-extremist laws overall, and of the ensuing freedom of speech restrictions, remains acute.

Criminal Prosecution

For public statements

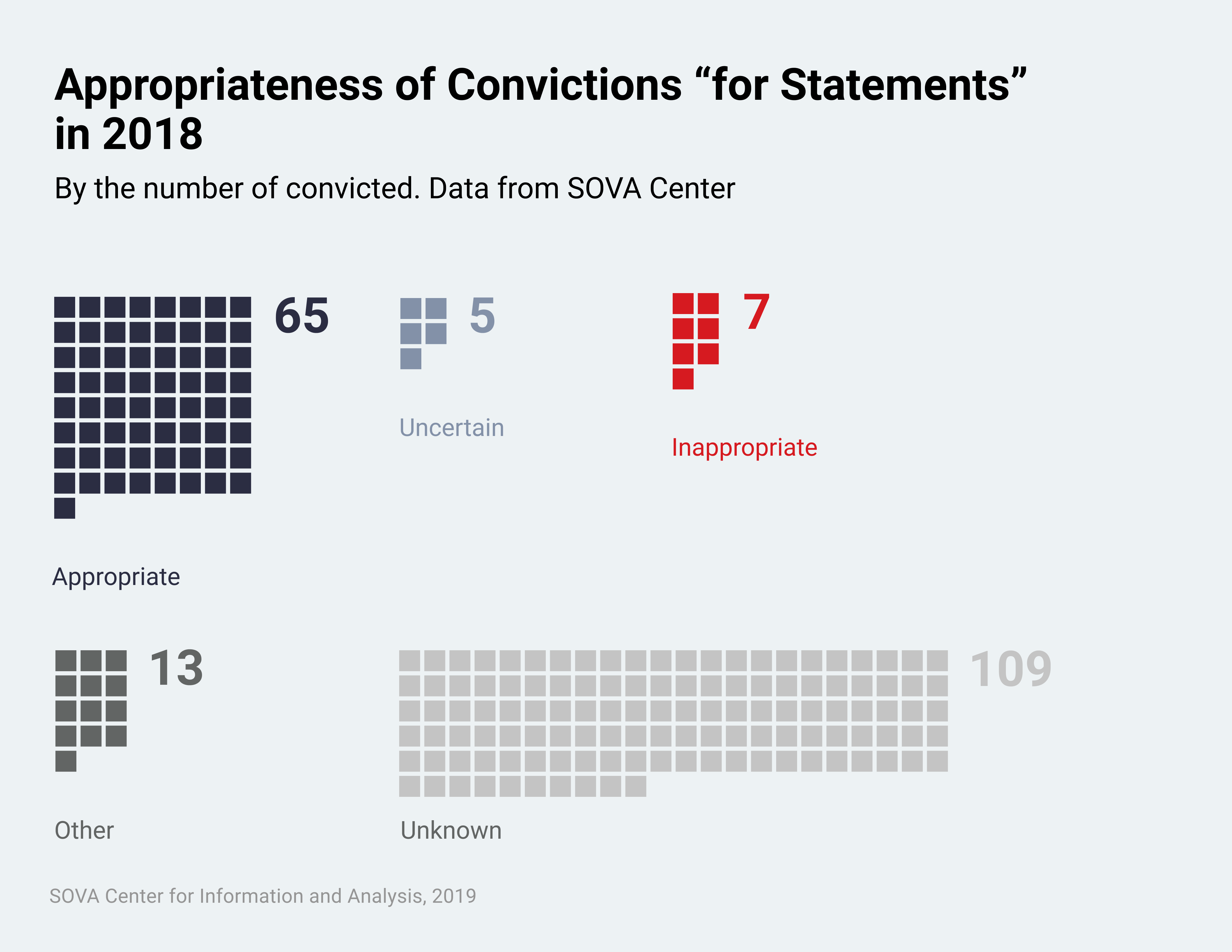

In 2018, the number of convictions passed down for “extremist statements” (incitement of hatred, calls for extremist and terrorist activity and so on) continued to dominate in comparison to all other convictions for “extremist crimes” combined. However, the annual increase in such convictions has stopped. SOVA Center knows of 183 convictions against 192 people[3] in 65 regions of the country.[4] This is slightly less than in 2017, when we learned about 197 such convictions against 253 people in 70 regions of the country. These figures do not include convictions we consider wrongful, but there were also fewer of these: in 2018, we considered six convictions against seven people wrongful,[5] and these convictions will not be further considered in this report.

These statistics do not include clearing of criminal responsibility with payment of a court fine. This kind of outcome appeared in Russian law (Article 762 of the Criminal Code) in 2016. As far as we know, cases on “extremist statements” ended in this way twice in 2017 and ten times in 2018. We can only welcome the appearance of this alternative to a criminal conviction “for words.”

Last year, we changed our system of conviction classification. It has become more detailed.

We deem appropriate only those convictions where we can assess with certainty the content of the statements and where we believe that courts issued convictions in accordance with the norms of the law, at least in respect of the actual content of the statement (although failure to account for other criteria may make some of these convictions wrongful overall). We know of 55 such appropriate convictions against 65 people.

In the vast majority of cases – labelled as “Unknown” (109 convictions against 109 people) – we know nothing or too little about the content of the publications or republications to be able to assess the appropriateness of these decisions. However, people whose prosecutions we can assume were appropriate on the basis of circumstantial evidence have also fallen into this category. This would include, for example, people who were previously part of an ultra-right group, people previously prosecuted under “extremist” administrative or even criminal articles, and those noted in the publications of law enforcement agencies for having called for violent actions. But since we could not access the text of the publications, we had to acknowledge that we could not fully assess the appropriateness of these prosecutions. After all, there have been cases when high-profile nationalist activists have been prosecuted for entirely innocent publications.

Convictions that we had trouble assessing fell into the category of “Uncertain” (five convictions against five people): for example, cases where we are inclined to treat one of the charges as appropriate and another as wrongful.

Similarly, our category “Other” (13 convictions against 13 people) is topped off by individuals convicted, probably appropriately, under extremist articles of the Criminal Code, but whose prosecution cannot be classified as combatting nationalism and xenophobia. These would include, for example, supporters of the Artpodgotovka movement or anarchists calling for attacks on officials at government agencies.

Speaking about statistics overall, unfortunately, we know of far from all convictions. According to data posted on the Supreme Court’s website,[6] during just the first six months alone of 2018, parts 1 and 2 of Article 148, Article 205,2 Article 280, Article 2801, Article 282, Article 3541 of the Criminal Code were the main articles of accusation of “extremist statements” for 283 people and additional articles of accusation for 81 people. Thus, from 283 to 364 people were convicted for “extremist statements.”[7] And these Supreme Court figures are slightly lower than for the same period of the previous year.[8]

The ever-popular Article 282 of the Criminal Code (“Incitement of Hatred or Enmity”) was used in the 155 convictions of 161 people that we know of.[9] In the overwhelming majority of cases (108), this article was the only article listed in the conviction.

Only Article 280 of the Criminal Code (“Public Appeals for Extremist Activity”) was used in 15 convictions of 15 people. In another 22 cases, it was combined with Article 282.

Article 2801 of the Criminal Code (“Public Appeals to Perform Actions Aimed at Violating the Territorial Integrity of the Russian Federation”) was applied in one conviction. As in the previous year,[10] a suspended sentence under this article was handed down to a member of the Community of Indigenous Peoples of Russia (OKRN). This time, Ivan Kolotilkin, the leader of the Ulyanovsk branch of the OKRN was punished.[11] In his case, as in the case of last year’s OKRN leader from Samara, Article 2801 was applied in conjunction with Article 282.

Article 3541 of the Criminal Code (“Denial of Facts Established by Decision of the International Military Tribunal for the Trial and Punishment of Key European War Criminals, Approval of Crimes Established by the Verdict, and the Dissemination of Knowingly False Information about the Activity of the Soviet Union During the Years of the Second World War”) was applied in three convictions. It was the sole article in only one case: in Stavropol Krai, a 20-year-old local resident was sentenced to 150 hours community service for a photograph “with raised hand in the form of a gesture similar to the Nazi salute” near the memorial “To Soldiers who Perished in the Great Patriotic War,” which was published on a social network page.[12]

The most recent case against the Perm-based activist Roman Yushkov ended in an unusual manner. He was convicted under Article 282 and Part 1 of Article 3541 of the Criminal Code for posting links on his Facebook page to the article “Jews! Pay the Germans Back the Money for Fraud with the "Holocaust six millions Jews!"” [author's English in the inside quote] However, Article 3541 of the Criminal Code allows for appeal to a jury, which Yushkov took advantage of, and he was acquitted by the jury.[13]

Naturally, articles concerning “extremist statements” can be combined with totally different articles, usually those concerning crimes against the person or property.[14]

For example, the case of Vladimir Dyachenko, the leader of the Stavropol cell of Russian National Unity (RNE) and an ideologue of the neopagan religious group Children of Perun, featured, along with the illegal possession of weapons and drugs, voice recordings of conversations in which Dyachenko spoke about killing “non-Slavs” by hitting them on the head with armature and slitting their throats.[15]

In Chuvashia, the republic’s Supreme Court convicted Sergey Ilyin, a former volunteer for the battalion of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN, banned in Russia), under Part 3 of Article 359 (“Participation of a Mercenary in an Armed Conflict), parts 1 and 3 of Article 3541, Part 1 of Article 282, and Part 2 of Article 280 of the Criminal Code. In addition to participating in military actions, Ilyin was accused of posting certain materials to social networks. In total, he was given a prison term of three-and-a-half years and fined 50,000 rubles.[16]

It is worth taking separate note of convictions under Article 2052 of the Criminal Code (“Public Calls for Terrorist Activity”), which became noticeably more popular in 2017 and 2018. According to data from the Supreme Court, this article was the main article of accusation for 39 people and an additional article of accusation for 11 people in the first half of the year.

SOVA Center is aware of 24 convictions handed down against 25 people under Article 2052 of the Criminal Code (that is, one-quarter of the actual convicted persons). In eight cases, it was the only article in the conviction. In four of the eight convictions, it was applied for calls to military jihad and support of ISIS.[17] Four of the other convicted persons included a supporter of Misanthropic Division,[18] a former member of RNE, an anarchist, and a cadet at the military medical academy who called for attacks on members of the authorities.

Article 2052 was also combined with other “extremist articles,” for example, with Article 280 (in two cases), Article 282 (in six cases), and both of these articles (in three cases). In almost of all these “integrated” cases, it was applied for radical Islamic statements. The exception was the conviction handed down by the Far Eastern Military District Court under Part 2 of Article 280, Part 1 of Article 282, and Part 2 of Article 2052 in relation to two residents of Altai Krai for creating a social media group where calls to violence against Muslims and members of “peoples of the Caucasus and Central Asia” were posted.[19]

In the remaining cases, this article was combined with other general crime articles of the Criminal Code, including threat of murder, distribution of narcotics, and illegal acquisition and possession of weapons (Article 222 of the Criminal Code). At different times, members of the group Russkaya Respublika Rus [The Russian Republic of Rus’] were convicted of weapons possession and terrorist propaganda:[20]Velsk resident Vasily Pivkozak was sentenced to three years in a general regime penal colony for explosives found in his home and some posts on the social network VKontake[21], and Severodvinsk resident Aleksey Lebedev was sentenced to six years in a general regime penal colony for similar actions[22] (Igor Byzov of Arkhangelsk was only convicted under articles 282 and 280 and was sentenced to a two-year suspended sentence[23]).

We do not know the content of most of the incriminating statements, particularly of alleged calls to military jihad, but we cannot exclude the possibility that parts of these criminal cases were fabricated.[24]

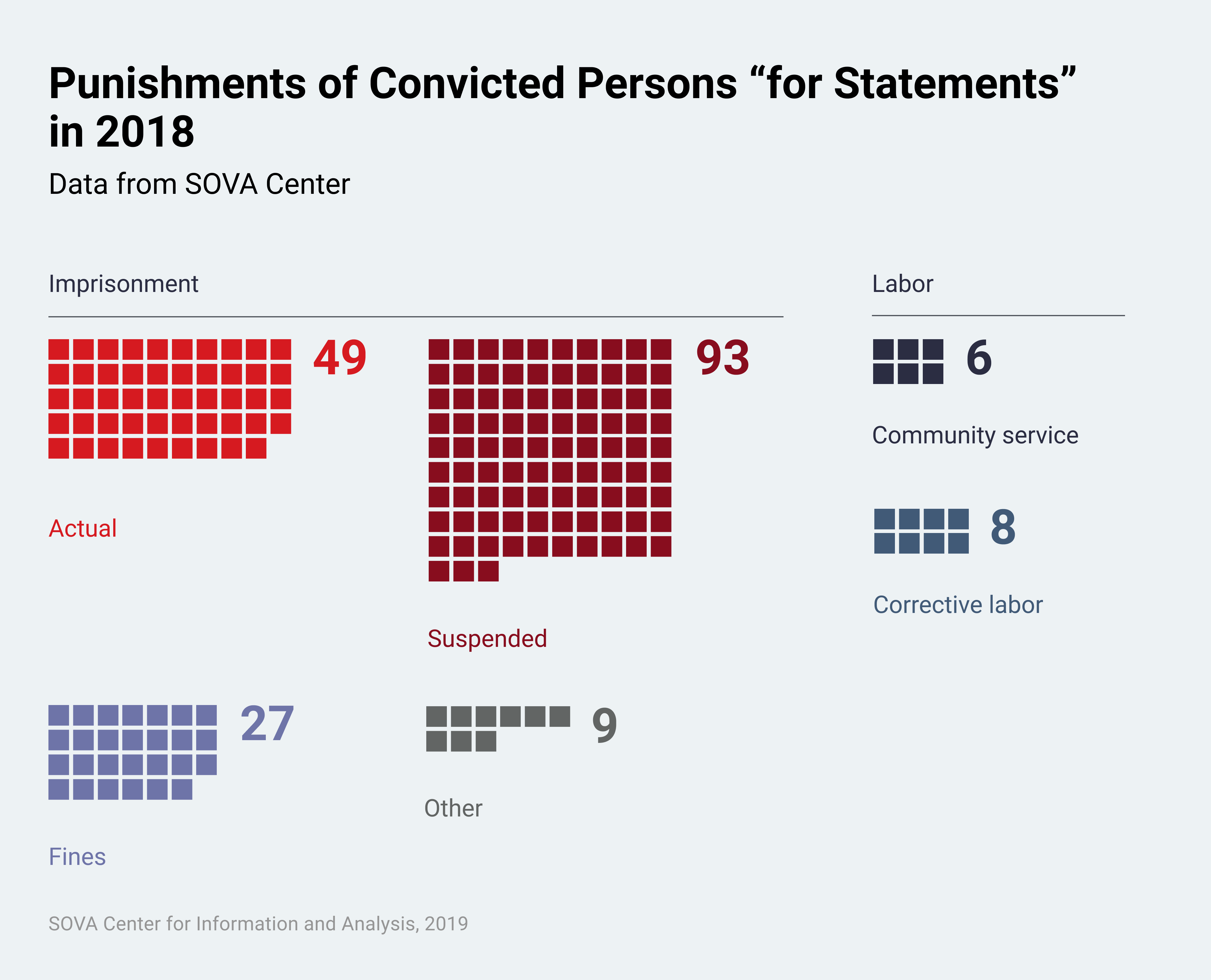

The punishments for those convicted for public statements were distributed as follows:

- 49 people were sentenced to prison term;

- 93 received suspended prison terms without any additional sanctions;

- 27 were convicted and fined in various amounts;

- eight were sentenced to corrective labor;

- six were sentenced to community service;

- five were subjected to forced treatment;

- four were released because of expiration of the statute of limitations;

- one was given disciplinary measures;

- one was acquitted.

The number of people sentenced to prison rose slightly in comparison to the previous year (a year ago we reported 47 people).

Twenty-three of the 49 people sentenced to prison received terms in conjunction with charges not related to statements (violence, arson, robbery, possession of narcotics).

Predictably, the punishments were harsher for crimes committed as part of Article 2052 of the Criminal Code. Twelve people were sentenced to imprisonment for radical Islamist videos and publications posted on the internet, as well as for radical publications connected with events in Ukraine (the aforementioned supporters of Misanthropic Division and OUN).

Nine people were already in prison and their terms were extended.

Five people were convicted for “extremist statements” for a second time, which greatly increases the risk of imprisonment. As in the previous year, this group included the leader of the Parabellum movement and activist in Kvachkov’s People’s Militia of Russia (the former NOMP) Yury Yekishev, who received two years’ imprisonment for publishing a notorious ani-Semitic caricature from the early 20th century with the inscription “We will drive out this vile beast with the Russian twig so that this vermin does not defecate on us anymore.”[25] [the original is rhymed]

Although, 12 people received prison terms without the circumstances stated above (or, we are not aware of them in certain cases). We are talking about sentences imposed in Perm, Syktyvkar, Tula region, Perm Krai, Ufa and some other regions for publishing various materials on the social network VKontakte (video and audio clips, comments, etc.), including calls for violence. We do not know anything about who these people were and what the content of the publications for which they were convicted was, but this is why we can assume that most of them did not carry out large-scale campaigns and therefore these sentences are most likely unjustifiably harsh.

The situation has deteriorated in comparison with the previous year (we reported on seven such convictions in 2017 and five in 2016), but did not reach the peak of 16 in 2015. For 2013 and 2014 we learned about two such convictions for each year.[26]

The share of suspended sentences has remained virtually unchanged at 48.5% (93 out of 192) instead of the 49% (113 out of 228) of 2017. The share of those convicted (41 people) sentenced to punishments not connected with real or suspended terms of imprisonment but instead to mandatory and corrective labor or fines continued falling for the third year. People punished in this way included Vladimir Ratnikov (Komarnitsky), who was given 160 hours of community service for publishing songs by the groups Kolovrat [an old Russian name of the solar symbol] and Bandy Moskvy [Gangs of Moscow] on his VKontakte page,[27] and the ultra-right activist Dina Garina, who was sentenced by a Saint Petersburg court to 120 hours of community service for insulting representatives of authorities.[28]

Of the additional punishments in 2018, we know of the following: bans on holding senior positions (two cases), engaging in social activism (two cases), working in the media (three cases), organizing public events (two cases), and operating a means of transportation (one case). Beyond this, there is an entire array of additional punishments connected with internet use. And while we can understand measures like bans on public statements on the internet (12 cases) or moderating and administering social networks or sites on the internet (four cases), then total bans on using the internet (four cases) appear strange and excessive, since it is difficult to imagine daily life, including work and study, without the internet. And it would also be extremely difficult to enforce such a ban.

The confiscation of “tools of the crime” such as laptops, mobile telephones, or tablets used to publish statements, which are the subject of investigation, seems equally excessive and harsh.

As usual, the overwhelming majority of verdicts were made for materials posted on the internet – 172 of 183, or 94% (as compared to 96% in 2017).

These materials were posted on:

- social networks – 155 (including VKontakte – 98, unnamed social networks – 55, which were likely also VKontakte, Odnoklassniki –2);

- YouTube – 1;

- internet-based media – 2 (comments on articles);

- radio stations – 1;

- forums – 1;

- online (not specified) – 12.

We have recorded this same approximate breakdown for seven years.[29] The social network VKontakte remains one of the richest sources for initiating criminal cases. What is surprising is that VKontakte continues to be the most popular social network among young Russian people, including ultra-right youth, in spite of obvious attention it receives from E Centers and investigative committees.

This concerns the following types of materials (various types of materials can be posted to a single account or even a single page):

- video clips – 49;

- images (drawings) – 31;

- photographs – 22;

- audio (songs) – 36;

- texts (including republished books) – 32;

- remarks, commentary (on social networks and in forums) – 15;

- unknown – 17.

In general, this breakdown has been typical of the past seven years, with prosecution for the most eye-catching and accessible materials – videos, drawings, and songs. And, as usual, the overwhelming majority of these materials were republications. It was only noted three times that the convicted persons themselves prepared the materials that became the subject of court proceedings.

The same can be said of the texts of articles published in reposts. Remarks and comments on social networks and in forums could probably be referred to as “original texts,” but it seems to us that this kind of idle chatter does not merit a criminal investigation in light of its small audience and the difficulty unearthing them.

We must again report that in 2018 the quality of enforcement of the law remained the same as several years ago. Statements about all these convictions mention nothing about the audience seeing this “sedition.” Virtually no mention is made of the number of “visitors” and “friends,” and investigative committees have always gotten away with the standard phrase “was uploaded for public access.” The main argument used for this kind of decision is that, since the material is posted openly, the whole world can see it. However, as our years of observations have shown, these pages were only visited by a small number of the user’s “friends” on social networks prior to their viewing by law enforcement agencies.

However, by year’s end judges had started to make account for the resolution on extremist crimes made by the Plenum of the Supreme Court and adopted on September 20, 2018.[30] For example, in October a criminal case under Article 282 of the Criminal Code against a 35-year-old local resident of Krasnoyarsk Krai accused of publishing xenophobic images on VKontakte was closed for absence of a crime event.[31] The investigation found that the accuser’s actions were of little significance and, following the Supreme Court’s recommendation, deemed that the overall content of the page was not aimed at promoting hate and that the publication did not attract broad attention from the public.

Convictions for statements made offline were slightly higher than in the previous year: 11 against 8 in 2017. They are distributed as follows:

- voices during an attack – 1;

- leaflets – 5;[32]

- graffiti – 2;

- preparation and distribution of brochures – 1;

- members of ultra-right groups for unknown episodes of propaganda – 2.

We do not have any fundamental doubts about the appropriateness of these convictions. However, we do have doubts about the need for criminal prosecution for graffiti on the streets. We add only that in all the remaining cases it is necessary to take into account not only the content of these statements (leaflets, brochures), but also other factors affecting the danger they pose to society, primarily the actual size of the audience.[33]

For participation in extremist communities and banned organizations

We are not aware that there were any convictions in 2018 under Article 2821 of the Criminal Code (“Organization of an Extremist Community,” even though in the first six months there were three), and prosecutions of ultra-right groups occurred more under Article 2822 (“Organization of the Activity of an Extremist Organization”) in approximately the same amount as the previous year.[34] We know of three such convictions against six people in three regions of the country[35] (in 2017 we were aware of four convictions against six people in four regions), and all three related to Ukrainian organizations.

The first two cases concerned the ultra-right Ukrainian movement Right Sector, which is banned in Russia.

In Bryansk Oblast, the Sevsk District Court sentenced 28-year-old Ukrainian citizen Alexander Shumkov to four years in a general regime correctional facility. According to the investigation, Shumkov was the personal bodyguard of Dmitry Yarosh, the leader of Right Sector, and participated in the blockade of Crimea. Shumkov served in a military unit in the village of Chornobaivka, Bilozerka District, Kherson Oblast and was arrested in August 2017 while attempting to enter Russia. In addition, Shumkov took part in a number of actions “intended to intimidate residents of Kherson Oblast demonstrating against the blockade of Crimea and calling for the restoration of economic and political ties with Russia.”[36]In other words, all the incriminating actions took place outside of Russia.

Meanwhile, the Pervomaysk District Court in Rostov-on-Don sentenced 42-year-old Ukrainian citizen and member of Right Sector Roman Ternovsky to two years and three months in a general regime facility. Ternovsky served in command positions in the Ukrainian Volunteer Corps of the Border Guard Service, but, according to the investigation, he came to Russia in December 2016 and published “materials intended to draw attention to the activities of the extremist organization Right Sector” for general access on Facebook.[37]

The last case concerned a different banned ultra-right movement: Misanthropic Division. In Rostov-on-Don, a conviction was handed down in a case against four activists of this group: Alexander Vishnyakov, Sergey Konev, Andrey Bezuglov, and Ruslan Pavlyuk. According to the investigation, Pavlyuk got Bezuglov and Konev involved. On January 10, 2017, these three people and Vishnyakov attacked Vladislav Ryazantsev, a journalist from the human rights publication Caucasian Knot, and beat him. According to Ryazantsev, “One of the attackers mentioned in his testimony that the cause of the attack was that Caucasian Knot was distributing false information about nationalist movements.” The court found all four young people guilty depending on each one’s participation under Article 116 (“Battery”), Part 2 of Article 2822, and Part 1.1 of Article 2822 of the Criminal Code (“Involvement in the Activities of an Extremist Organization”) and sentenced them to various terms of imprisonment.[38]

We do not know anything about convictions made against right-wing radicals for organizing and participating in the activity of a terrorist organization (Article 2054), and also for organizing and participating in terrorist communities (Article 2055), although some nationalist organizations had previously been banned as terrorist organizations.

Federal List of Extremist Materials

In 2018, the Federal List of Extremist Materials was updated 38 times (a year earlier it was updated 33 times), 466 entries were added to it (a year ago 330 items were added), and it grew from 4,345 to 4,811 entries.[39]

Thus, additions to the list again intensified, wiping out the 2017 decline driven by an order of the Prosecutor General issued in the spring of 2016 that largely centralized the procedure for banning materials due to extremism.[40]

Additions to the list are distributed across the following topics:

- xenophobic materials of Russian nationalists – 250;

- materials of other nationalists – 22;

- materials of Islamic militants and other calls of Islamists for violence – 43;

- other Islamic materials – 40;

- materials of Hizb ut-Tahrir – 21;

- other religious materials (materials of Jehovah’s Witnesses) – 20;

- extremely radical anti-Russian speeches from Ukraine (we distinguish them from “other nationalists”) – 4;

- other materials from the Ukrainian media and internet – 6;

- anti-government materials calling for disorder and violence – 6;

- materials with works of fascist and neo-fascist classic authors – 3;

- historical books and other historical texts – 5;

- large heterogeneous selections of texts banned in their entirety – 1;

- parody materials – 16;

- peaceful opposition websites – 4;

- radical anti-Christian websites – 2;

- fiction – 1;

- anti-Islamic materials – 2;

- unidentifiable materials – 40.

At a minimum, 402 of the 466 items are materials from the internet (a year ago it was 304 of 330 items) including various types of video and audio recordings and pictures, mainly from social networks. Offline materials included books by nationalists, the Nazi classics, Orthodox fundamentalists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Islamic authors, as well as newspapers and leaflets.

Sometimes, it is not completely clear where precisely a piece of banned material was posted. For example, item 4,591 is described as a “graphic illustration of soldiers carrying out an attack with the text ‘They fought for the homeland! And you hand it out to the black asses without a fight’” without any source information. And in terms of item 4,721 – “Informational Material – the article ‘French March,’” not just the place of the material’s publication is unclear, but also everything about the article in general, since articles with the same name and totally different content can be found absolutely anywhere.

Unfortunately, nothing we have written about the list’s shortcomings for almost 10 years now has changed,[41] not counting the proliferation of strange and illiterately described items. The list continues to contain all manner of bibliographic, grammatical, and spelling mistakes and errors along with haphazardly written descriptions reminiscent of notes for internal use only. Duplicates with different publication information posted on different internet addresses were repeatedly added to the list; there were 236 such duplications as at the end of 2018.

Furthermore, some materials inevitably continue to be wrongfully deemed extremist. In 2018, at least 63 materials were added to the list (materials of Jehovah’s Witnesses, non-violent Islamic materials, non-violent materials from Ukrainian websites, and some others).

Organizations Banned for Being Extremist

In 2018, seven organizations were added to the list of extremist organizations published on the website of the Ministry of Justice, which is slightly higher than in the previous year, when six organizations were added.

Over the year, the following radical organizations banned in December 2017 were added to the list:

- The neo-Nazi group Schtolz (Schtolz Khabarovsk, Schtolz Far East, Schtolz-Iugent),[42] whose members attacked representatives of liberal and left-wing movements and youth subcultures, as well as LGBT people. Officials first noticed this group in April 2017 after Anton Konev, a 17-year-old group member, attacked people in an FSB receiving room, leading to the death of two people in the building and the attacker himself.

- Two soccer “firms”: Sector 16, a group of soccer fans from Bugulma Municipal District in the Republic of Tatarstan (S-16 or BugulmaUltras)[43] and a Tula-based fan group, which was incomprehensibly described in the list as “the organization of soccer fans Firma of soccer fans of Pokolenie [Generation].”[44]

- Nezavisimost [Independence], a regional non-governmental organization for the promotion of national self-determination of the peoples of the world, founded by members of ultra-right organizations but apparently inactive, which was apparently added to the list because one of its founders was on “the list of Rosfinmonitoring” (list of organizations and people involved in terrorist or extremist activities).[45]

The right-wing populist Interregional Grassroots Movement Artpodgotovka [Preparatory Fire],[46] which formed around the Saratov-based blogger Vyacheslav Maltsev, was also added to the list.

In addition, the list included two recently banned organizations. The first is the religious group titled “In Honor of the Icon of the Mother of God Derzhavnaya” [The Majestic one, name of the icon] in Novomoskovsk, Tula Oblast,[47] which is in fact a convent for women followers of the fundamentalist priest Father Vasily Novikov, who died in 2010, some of whose sermons were banned for promoting ethnic and religious enmity.

The second organization is the Karelian regional branch of the interregional youth charity public organization Youth Human Rights Group (MPG)[48], which was liquidated because its founder was listed as Maksim Efimov, who is on “the list of Rosfinmonitoring.” We believe that the case against Efimov was wrongfully initiated and that the inclusion of MPG on the list of extremist organizations contravenes the law, since a court shut it down but never deemed it extremist.[49]

Thus, as of February 11, 2019, the list includes 71 organizations,[50] whose activities were banned in court proceedings and whose further activities are punishable under Article 2822 of the Criminal Code (“Organization of the Activities of an Extremist Organization”).

Besides this, the list of organizations deemed terrorist, which is published on the FSB’s website, was also updated in 2018. For the year, two organizations were added – Chistopol Jamaat[51] (entry 28) and Rokhname ba sui davlati islomi (Travel Guide to the Islamic State)[52] (entry 29).

Other Administrative Measures

Prosecution for administrative violations

Unlike criminal law enforcement, administrative law enforcement is gaining momentum: the number of those punished under administrative “extremist” articles in 2018 grew noticeably, so the slowdown in growth in 2017 should be taken as an exception. Our data here are less complete than for criminal cases: data appears on the websites of prosecutor’s offices and courts with a great delay and far from all is published. The statistics we compiled are put forward without account of the decisions that we consider wrongful.[53]

We learned about 133 people who were held responsible in 2018 under Article 20.3 of the Code of Administrative Offenses (“Propaganda or Public Demonstration of Nazi Attributes or Symbols, or Attributes or Symbols of Extremist Organizations, or other Attributes or Symbols, Propaganda or Public Demonstrations of which is Banned by Federal Laws”), of which three were minors (last year we wrote about 136 convicted under this article).

According to the statistics of the Russian Supreme Court, 963 people were convicted under Article 20.3 of the Code of Administrative Offenses (CAO) in the first half of 2018,[54] a figure which stood at 1,665 for all of 2017.[55]

The majority of those punished under Article 20.3 posted images of Nazi symbols and symbols of banned organizations like ISIS or Artpodgotovka to social media. There was a lot fewer of those punished for offline activities. These included two people strolling down the street in t-shirts with Nazi symbols (including a soccer fan in a t-shirt bearing the image of Totenkopf (“Death’s Head”)), two graffiti artists who drew swastikas in a pedestrian underpass and at a bus stop, two owners of concession stands selling items with Nazi symbols, and an automobile owner who attached a sticker with a banned symbol to his vehicle.

The number of prisoners punished for displaying their own tattoos with Nazi symbols rose. According to our information, in 2018 at least 53 people were punished (as compared to 46 in the previous year), while another three people displayed their tattoos outside of prison.

The majority of offenders were fined between 1,000 and 3,000 rubles. Eleven were sentenced to administrative arrest (from 3 to 10 days).

We learned about 210 people punished under Article 20.29 of the CAO (“Production and Distribution of Extremist Materials or Symbols of Extremist Organizations”), four of them were minors (in 2017, we wrote about 203 people convicted under this article).

According to Supreme Court statistics, 1,133 people were convicted under Article 20.29 of the CAO in the first half of 2018.[56] For all of 2017, 1,846 were convicted.[57]

The majority of people convicted known to us paid small fines. Seven people were sentenced to administrative arrest. As concerns items on the Federal List of Extremist Materials, which are used in practice under Article 20.29 CAO, the attention of the prosecutors still remains concentrated upon an extremely small number: certain songs of groups popular among ultra-right wingers (Kolovrat, Grot, Argentina, Psikheya [Psyche], and others); songs of the Chechen bard Timur Mutsuraev; and ISIS videos. This again provides a vivid illustration of the absurdity of the existence of this monstrous list, which no one, even officials at E Centers, is capable of plowing through.

Fourteen people were held responsible under articles 20.3 and 20.29 of the CAO simultaneously. They were all fined.

Of note is the rare punishment under Article 13.11.1 of the CAO (“Publication of Vacancies Containing Discriminatory Restrictions”): in Noyabrsk, Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, the head of the company Pegas OOO was fined for posting a want ad on social media with the proviso that the position could not be held by people “of a non-Slavic appearance.”

When speaking of punishments under administrative articles, we should note that “tools of the commission of a crime” (laptops, tablets, smartphones, etc.) whose value exceeded the amount of fines by many times, were confiscated from convicted persons.

Here we reported on decisions that we consider more or less appropriate. However, we know of at least 29 cases of wrongful punishments under Article 20.3 of the CAO and 17 cases under article 20.29. Thus, for 357 appropriate decisions, there were 46 wrongful ones, and the share of wrongful decisions (almost 11.5%) dropped slightly in comparison with the previous years: 72 wrongful decisions against 399 appropriate decisions (that is, 15%).

Blocking on the Internet

The fight of prosecutors against extremist content on the internet carried out by blocking access to banned (or other supposedly “dangerous”) materials remains one of the top priorities in the battle against extremism.

A system of internet filtering is operating on the basis of a Unified Register of Banned Websites, which has been functioning since November 1, 2012. Based on the data of Roskomsvoboda website[58] (only the Federal Service for Supervision in the Sphere of Communications, Information Technologies and Mass Communications, Roskomnadzor, has the complete information), we believe that 611 resources have ended up on the register “for extremism” following a court decision in 2018 versus 296 a year earlier.[59] As at January 1, 2018, according to preliminary calculations, the number of resources blocked in this way for the lifetime of the register itself amounts to at least 1,825.[60] After comparing the data of Roskomsvoboda with the data of Roskomnadzor, we believe that in reality there are actually many more court decisions on the blocking of specifically “extremist content.”

According to our observations, the lion’s share of the resources that ended up in the Unified Register over the year were materials from various types of Russian nationalists ranging from xenophobic songs to the books of well-known nationalist authors (76%) to the materials of Islamist fighters (from ISIS videos to Timur Mutsuraev's songs) (8%) and non-violent Muslim materials (5%). A noticeable percentage of resources were connected with Ukraine (from radical to non-violent publications of the Ukrainian media, 2% each), while less than 2% accounted for blocked Russian opposition resources and 1.5% were links to the classics of fascism. The remainder of blocked resources (less than 4%) were comprised of materials from other nationalists and Jehovah’s Witnesses, seditious anti-government materials, materials critical of the Russian Orthodox Church, parody materials banned as serious, and radical anti-Christianity websites (with the exception of neo-pagan nationalists).

The quality of these blockings continues to raise eyebrows and sometimes just sarcasm. A good example is the resource marked as “list of audio compositions found for the query ‘Pechki-Lavochki’[translates as ‘this and that, nothing in particular’, or ‘idle, friendly chat’]”. The highest-ranking response given for the query “Pechki-Lavochki” on Yandex is the song of the Belarussian folklore ensemble Syabry, which was popular in Soviet times. What is probably being referred to, however, is the song “Pechki-Lavochki” performed by the ultra-right artist The Czech, which was deemed extremist by the Rtishchevo District Court, Saratov Oblast on June 22, 2017 and added to the Federal List of Extremist Materials under entry no. 4202,[61] but this is impossible to understand from the descriptions in the register.

In general, we believe that the practice that has taken root over the past two years of blocking not specific websites or pages, but search results for keywords is mistaken (“Links to downloading audiofiles found using the keyword search ‘sacred revenge,’” “list of audiofiles found using the keyword search ‘Kolovrat kaskadery’” [Stuntmen; a song originally performed by the group Zemlyane, but reprised by the nationalist musical group Kolovrat – Trans.]), and these decisions are clearly wrongful: the keyword search results bring up completely different resources.

The number of obviously wrongful blockings is rising. For example, in 2018 materials of Jehovah’s Witnesses and non-violent Muslim materials were again found in the Unified Register. Resources blocked simply due to lack of understanding were also found in the register.

The Unified Register is supplemented with a separate register according to the Lugovoy law,[62] which envisages the extrajudicial blocking of websites with calls for extremist action and mass disorder, at the request of the Prosecutor General’s Office, but without court proceedings. This “Lugovoy register” is growing rapidly.

It is impossible to give even an approximate count of the resources in the register.

According to Roskomnadzor,[63] a total of 51,892 resources were blocked for extremism over the first three quarters of 2018 (data for the full year is not yet available). Almost all of these are not the websites themselves in relation to which a query was received from the Prosecutor General’s Office (there are almost 400 of these), but a “mirror” of these websites found by Roskomnadzor itself. And, judging by their number, these are not necessarily “mirrors” in the exact sense, but different websites with the same or very similar materials.

In its reports, Roskomnadzor itself identifies the following types of resources:

- materials with ISIS propaganda – over 17,000;

- materials of Hizb ut-Tahrir – almost 17,000;

- materials of banned organizations from Ukraine (Right Sector, UNA – UNSO, UPA, Stepan Bandera Tryzub [Trident, symbol of Ukraine], Brotherhood, Azov) – almost 5,000

- calls for “mass unrest, extremist activity, participation in mass (public) events conducted in violation of the established order” – 728

Roskomnadzor did not identify the other 12,000 resources.

On the other hand, this agency did report that illegal information was removed from 32,235 resources in the first three quarters of 2018 and that the blockings were lifted (it is possible that some of these were blocked previously). Thus, this register grew over this time period to reach approximately 20,000 entries.

The scale of the blockings is shocking, and it is not at all clear which specific resources the agency had in mind or how dangerous the propaganda was. It also remains unclear why these resources needed to be blocked so urgently that they required extrajudicial blocking. The number of wrongful sanctions in this register is also growing. Given such a large scale, it is inevitable that there will be resources blocked by mistake. It is telling that we know the least of all about blocked resources with calls for mass unrest created for mobilization to mass actions, since the “Lugovoy law” was apparently adopted specifically because of the need for such blockings. Experience has shown that it is usually impossible to prevent mass mobilization through blocking: in these cases, many distribution channels are used at the same time, and this information inevitably becomes known to people interested in it.

Technically, these two registers are placed separately on the website of Roskomnadzor, however, the procedure for using them is practically the same. According to a decision of Roskomnadzor, the blocking of a resource can happen for a concrete webpage address (URL), or, more widely, by a subdomain name, or by a physical address (IP).[64]

Our claims about the effectiveness and legitimacy of these mechanisms remain unchanged.[65] Every year, the situation changes only for the worse. These registers are swelling, and, unlike the Federal List, they are not published anywhere officially, which complicates public monitoring of this work. As a result, the system for blocking is cause for a great deal of criticism and leads inevitably to political arbitrariness, the pursuit of accountability, and restrictions in freedom of speech on the internet.

[1] Our work on this topic in 2018 was supported by the Norwegian Helsinki Committee, the International Partnership for Human Rights, and the European Union.

Infographics: Alexander Bogachev.

On December 30, 2016, SOVA Center was forcibly placed by the Justice Ministry on the register for “non-commercial organizations acting as a foreign agent.” We do not agree with this decision and have appealed it.

[2] Yudina, N. The Ultra-Right and Arithmetic: Hate Crime in Russia and Efforts to Counteract It in 2018 // SOVA Center. 2019. 22 January (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2019/01/d40542/).

[3] One more person was acquitted.

[4] Data as at February 18, 2019.

[5] See the concurrently published SOVA report: Kravchenko, Maria. “Inappropriate Enforcement of Anti-Extremist Legislation in Russia in 2018.”

[6] Consolidated statistical data about the activity of federal courts of general jurisdiction and magistrate courts for the first six months of 2018 // Official website of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation (http://www.cdep.ru/userimages/sudebnaya_statistika/2018/k3-svod_vse_sudy-1-2018.xls)/

[7] According to data posted on the Supreme Court’s website, there were none for whom parts 1 and 2 of Article 148 were the main article of accusation, it was an additional article for 6 persons, Article 2052 was the main and additional article for 39 and 11 persons, respectively, Article 280 was the main and additional article for 32 and 25 persons, respectively, Article 2801 was the main and additional article for three persons each, Article 282 was the main and additional article for 209 and 40 persons, respectively, and Article 3541 was the main and additional article for zero and two persons, respectively. These articles may be combined with each other or with other articles (see below), so the actual number of people convicted for statements is somewhere between the sum of the first numbers and the sum and the first and second numbers.

[8] Yudina, N. “Countering or Imitation: The State Against the Promotion of Hate and the Political Activity of Nationalists in Russia in 2017” // SOVA Center. 2018. March 2. (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2018/03/d38940/).

[9] From here on, all calculations are made using convictions known to us, even though, judging by the Supreme Court’s data, there are approximately three times as many convictions. But, given the amount of data we possess, we can assert that the observed patterns and proportions will be true for the entire number of convictions.

[10] “Togliatti: Verdict? Issued in the Case of Leader of the Community of Russian Indigenous People // SOVA Center. 2017. December 21. (http://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2017/12/d38543/).

[11] “Ulyanovsk: Court Sentences Activist from Community of Indigenous Peoples of Russia to Two-Year Suspended Sentence” // SOVA Center. 2018. November 8. (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/11/d40261/).

[12] “Izobilny: Community Service for a Photo with a Nazi Salute in Front of a Memorial to Soviet Soldiers” // SOVA Center. 2018. October 24 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/10/d40190/).

[13] “Perm: Roman Yushkov Acquitted in Third Criminal Case. Prosecutor’s Office Demands Quashing of Conviction” // SOVA Center. 2018. September 5 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/09/d39970/).

[14] For more information see: Yudina, N. The Ultra-Right and Arithmetic….

[15] “Yessentuki: Court Sends Local Ultra-Right Pagan Vladimir Dyachenko to Forced Treatment” // SOVA Center. 2018. August 13. (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/08/d39836/).

[16] “Cheboksary: Court Issues Sentence Against Former Marksman of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists Battalion” // SOVA Center. 2018. November 28. (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/11/d40332/).

[17] In another case, the content of statements on social networks was unknown, although it is highly likely that this was also Islamist propaganda, since the person convicted was from Uzbekistan.

[18] “Supreme Court Upholds Conviction of Kaliningrad Resident Convicted of Calls to Terrorism on Social Media” // SOVA Center. 2018. June 27 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/07/d39732/).

[19] “Residents of Altai Krai Convicted for Calls to Violence Against Muslims and Natives of the Caucasus and Central Asia Posted to Social Media” // SOVA Center. June 22. (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/06/d39595/).

[20] The name of this organization is similar to the name Russkaya Respublika, which gained notoriety after the publication of a “death sentence” for Nikolay Girenko in 2005.

[21] “Supporter of Russkaya Respublika Rus Convicted” // SOVA Center. 2018. March 6 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/03/d38966/).

[22] “Third supporter of Russkaya Respublika Rus Convicted” // SOVA Center. 2018. April 16 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/04/d39219/).

[23] “Arkhangelsk: One More Supporter of Russkaya Respublika Rus Convicted” // SOVA Center. 2018. March 14 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/03/d39001/).

[24] Kostromina, Darya. “Pro-terrorist Statements.” Cycle of Surveys “Criminal Prosecution for Terrorism in Russia and Abuse by the Government” // HRC Memorial. 2019. February 11 (https://memohrc.org/sites/default/files/presledovaniya-za-proterroristicheskie-vyskazyvaniya-2019-02-08.pdf).

[25] “Yuri Yekishev Sentenced to Two Years’ Imprisonment and Released in the Courtroom” // SOVA Center. 2018. January 26 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2017/11/d38333/).

[26] “Who has been Imprisoned for Extremist Crimes not of a General Criminal Nature” // SOVA Center. 2013. December 24 (http://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2013/12/d28691/).

[27] “Conviction in the Case of Publication of Racist Songs on Social Media by Leader of the Cherny Blok Movement Enters into Force” // SOVA Center. 2018. March 12 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/03/d38984/).

[28] However, Dina Garina was released from serving her punishment because the statute of limitations had expired. See: “Saint Petersburg: Court Hands Down Conviction in Case against Dina Garina” // SOVA Center. 2018. December 12 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/12/d40438/).

[29] See, for example: Yudina, N. “Anti-extremism in a Virtual Russia 2014–2015” // SOVA Center. 2016. June 29 (http://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2016/06/d34913/).

[30] “Resolution of the Plenum of the RF Supreme Court of September 20, 2018 on Judicial Practice in Criminal Cases with an Extremist Slant” // SOVA Center. 2018. September 20. (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/docs/2018/09/d40044/).

See also SOVA’s commentary on the resolution on extremist crimes // SOVA Center. 2018. September 25 (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/publications/2018/09/d40054/).

[31] “Krasnoyarsk Krai: Case Under Article 282 Closed for Absence of Crime Event” // SOVA Center. 2018. October 4 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/10/d40098/).

[32] Supporters of Volya parties distributed both leaflets.

[33] For more on approaches to law enforcement in this area, see: “Rabat Plan of Action on the Prohibition of Advocacy of National, Racial or Religious Hatred that Constitutes Incitement to Discrimination, Hostility or Violence // SOVA Center. 2014. November 7 (http://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2014/11/d30593/).

[34] These figures do not include prosecutions that we consider wrongful: in 2018, we deemed 10 convictions against 27 people wrongful. See: Kravchenko. M. “Wrongful Application of Anti-Extremist Laws in 2018.”

[35] This report does not look at convictions that were obviously wrongful or convictions of members of Hizb ut-Tahrir al-Islami.

[36] “Conviction in the Case against Dmitry Yarosh’s Personal Bodyguard Handed Down in Sevsk” // SOVA Center. 2018. June 5 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/06/d39498/).

[37] “Rostov-on-Don: Participant of Right Sector Sentenced to Four Years’ Imprisonment // SOVA Center. 2018. June 8 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/06/d39527/).

[38] “Rostov-on-Don: Verdict Issued in Case of Participants in Attack on Caucasian Knot Journalist.” 2018. March 26 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/03/d39074/).

[39] As of February 15, 2019, the list had 4,847 entries.

[40] For more information see: Kravchenko, M. “Wrongful Application of Anti-extremism Laws in November 2016” // SOVA Center. 2016. December 5 (http://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/publications/2016/12/d35943/).

[41] Yudina, N. “Countering or Imitation: The State against the Promotion of Hate and the Political Activity of Nationalists in 2017” // SOVA Center. 2018. March 3 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2018/03/d38940/).

[42] Deemed extremist by the Central District Court of Khabarovsk in December 2017. See: “Schtolz group Deemed Extremist in Khabarovsk” // SOVA Center. 2017. December 6 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2017/12/d38434/).

[43] Deemed extremist by the Bugulma City Court of the Republic of Tatarstan on May 28, 2018. See: “Bugulma: Group of Soccer Fans Sector 16 Deemed Extremist” // SOVA Center. 2018. August 9 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/08/d39816/).

[44] Deemed extremist by the Proletarsky District Court of Tula on June 14, 2018.

[45] Deemed extremist by the Moscow City Court on December 1, 2017. “Moscow City Court Bans Activities of Nezavisimost Foundation” // SOVA Center. 2018. August 29 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/08/d39930/).

[46] Deemed extremist by the Krasnoyarsk Krai Court on October 26, 2017 and confirmed by the Supreme Court in February 2018. See “Artpodgotovka Movement Deemed Extremist” // SOVA Center. 2017. October 26 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2017/10/d38151/).

[47] Deemed extremist by the Tula Oblast Court on July 25, 2016. See: “In Tula Oblast, Followers of Priest Vasily Novikov Deemed Extremist Organization” // SOVA Center. July 26 (https://www.sova-center.ru/religion/news/harassment/refusal/2016/07/d35086/).

[48] Liquidated under a decision of the Supreme Court of the Republic of Karelia of December 18, 2014. See: “MPG of Karelia Liquidated” // SOVA Center. 2015. January 26 (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/persecution/2015/01/d31110/).

[49] “MPG Karelia Added to the List of Extremist Organizations” // SOVA Center. 2018. November 11 (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/persecution/2018/11/d40252/).

[50] Not counting the 395 local organizations of Jehovah’s Witnesses banned along with their administrative center and listed with this center as one item.

The NGO “On the Course to Truth and Unity (Russian nationwide movement On the Course to Truth and Unity, the all-Russian political party On the Course to Truth and Unity, the political party On the Course to Truth and Unity), that is, an association of followers of the “dead water” teachings with nationalistic connotations that was deemed extremist by the Maykop District Court in the Republic of Adygea on May 7, 2018, was added to the list in February 2019. [For “dead water” see Russian folktales symbolism of dead and living water]

[51] For more on this organization, see: “Case of Chistopol Jamaat Closed” // Radio Svoboda. 2017. March 23 .

[52] See: “FSB Exposes Large Tajik Online Community of IS Recruiters” // Nastoyashchee vremya. 2016. August 11.

[53] For more on this, see the concurrently published report on wrongful application of anti-extremism laws.

[54] Report on the work of general jurisdiction courts on the review of cases against administrative offenders for the first half of 2018 // Official website of the Supreme Court (http://www.cdep.ru/userimages/sudebnaya_statistika/2018/F2-svod_vse_sudy-1-2018.xls).

[55] Report on the work of general jurisdiction courts on the review of cases against administrative offenders in 2017 // Official website of the Supreme Court (http://www.cdep.ru/userimages/sudebnaya_statistika/2017/F2-svod-2017.xls).

[56] Report on the work of general jurisdiction courts on the review of cases against administrative offenders for the first half of 2018…

[57] Report on the work of general jurisdiction courts on the review of cases against administrative offenders for 2017…

[58] See: The Unified Register of Banned Websites // Roskomsvoboda (http://reestr.rublacklist.net/) [name plays on “Roskomnadzor”, the banning entity, and svoboda, freedom].

[59] See the updated list: “‘Extremist Resources’ in the Unified Register of Banned Websites” // SOVA Center (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/docs/2019/01/d40512/.

[60] Extremism only plays a very small role in this register; according to Roskomsvoboda, the register had a total of 147,186 entries as at February 20, 2018.

According to Roskomnadzor, “in connection with the presence of banned information,” 53,848 websites and/or URLS were entered into the Unified Register for the first quarter of 2018, 49,212 were entered for the second quarter, and 58,111 were entered for the third quarter. See: “Report on Activities” // Official website of the Federal Service for Supervision in the Sphere of Communications, Information Technology, and Mass Communications. [Access date: February 12, 2019] (http://www.rkn.gov.ru/plan-and-reports/reports/p449/)/.

[61] “Federal List of Extremist Materials Grows to Entry 4,202” // SOVA Center. 2017. August 30 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2017/08/d37779/).

[62] The full name is “On Amendments to the Federal Law ‘On Information, Information Technologies, and the Protection of Information.”

[63] Reports on the activities of Roskomnadzor // Official website of the Federal Service for Supervision in Communications, Information Technologies and Mass Communications (http://www.rkn.gov.ru/plan-and-reports/reports/p449/).

[64] This leads to the blocking of many obviously innocent websites that simply happen to be on the same server.

[65] See, for example: Yudina, N. “Anti-extremism in Virtual Russia….”