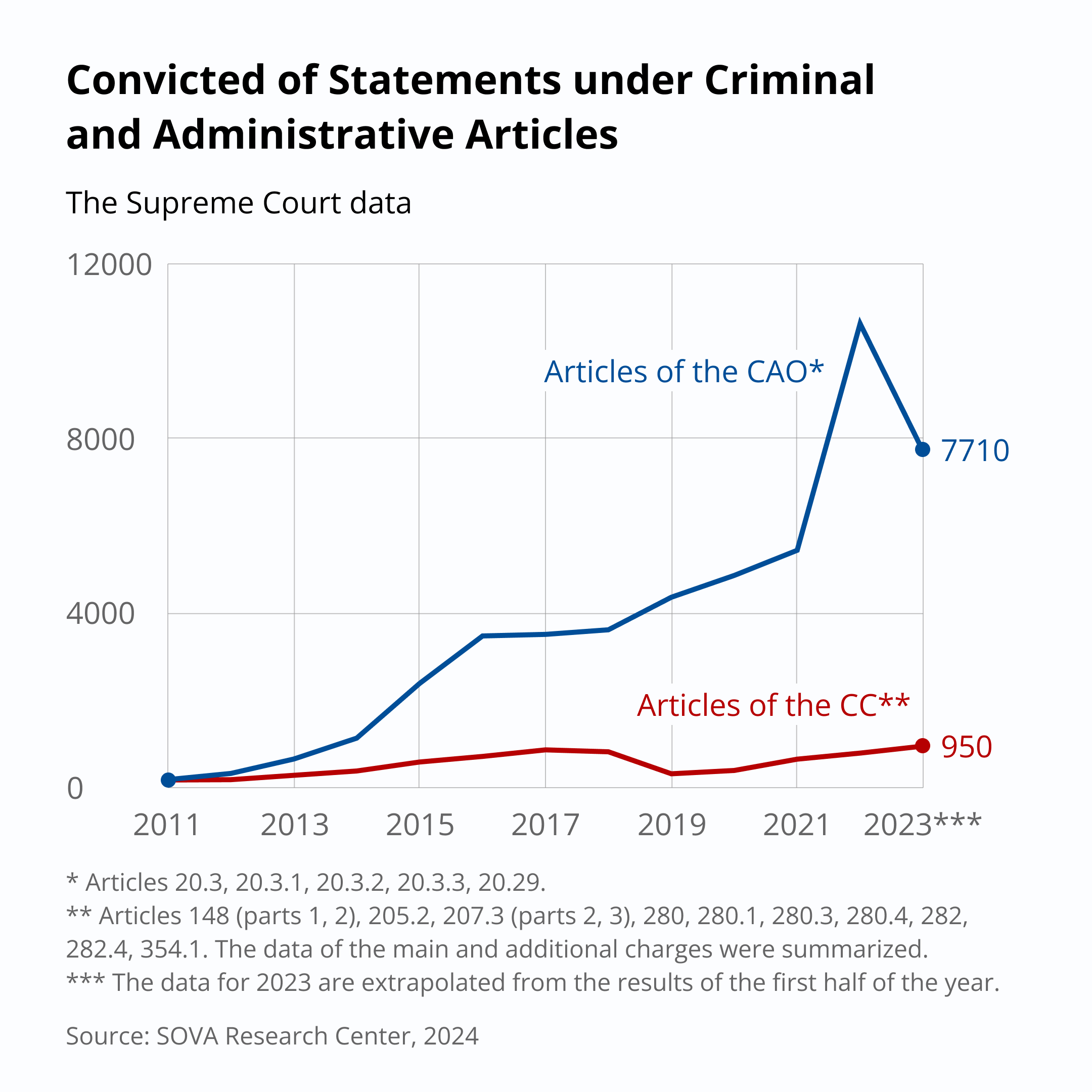

This report focuses on countering the incitement of hatred, calls for violent action, and political activity of radical groups, through the use of anti-extremism legislation. We are primarily interested in countering nationalism and xenophobia, but in reality the government’s anti-extremism policy is focused far more broadly, as reflected in the report. This counteraction relies on a number of articles of both the Criminal Code (CC) and the Code of Administrative Offenses (CAO), mechanisms for banning organizations and “informational materials,” blocking online content, etc.

This report does not address countering hate crimes: they were covered in an earlier report[1]. Another report, published in parallel, examines the cases of law enforcement that we consider unlawful and inappropriate; it also examines the legislative innovations of the past year in the field of anti-extremism[2].

Summary

Criminal Prosecution

For Public Statements

For Participation in Extremist and Terrorist Groups and Banned Organizations

Federal List of Extremist Materials

Banning Organizations as Extremist and Terrorist

Prosecution for Administrative Offences

Crime and punishment statistics

Summary

This report examines anti-extremism law enforcement, excluding two major sections — hate crime prosecutions and clearly abusive, inappropriate enforcement, subjects of two separate reports.

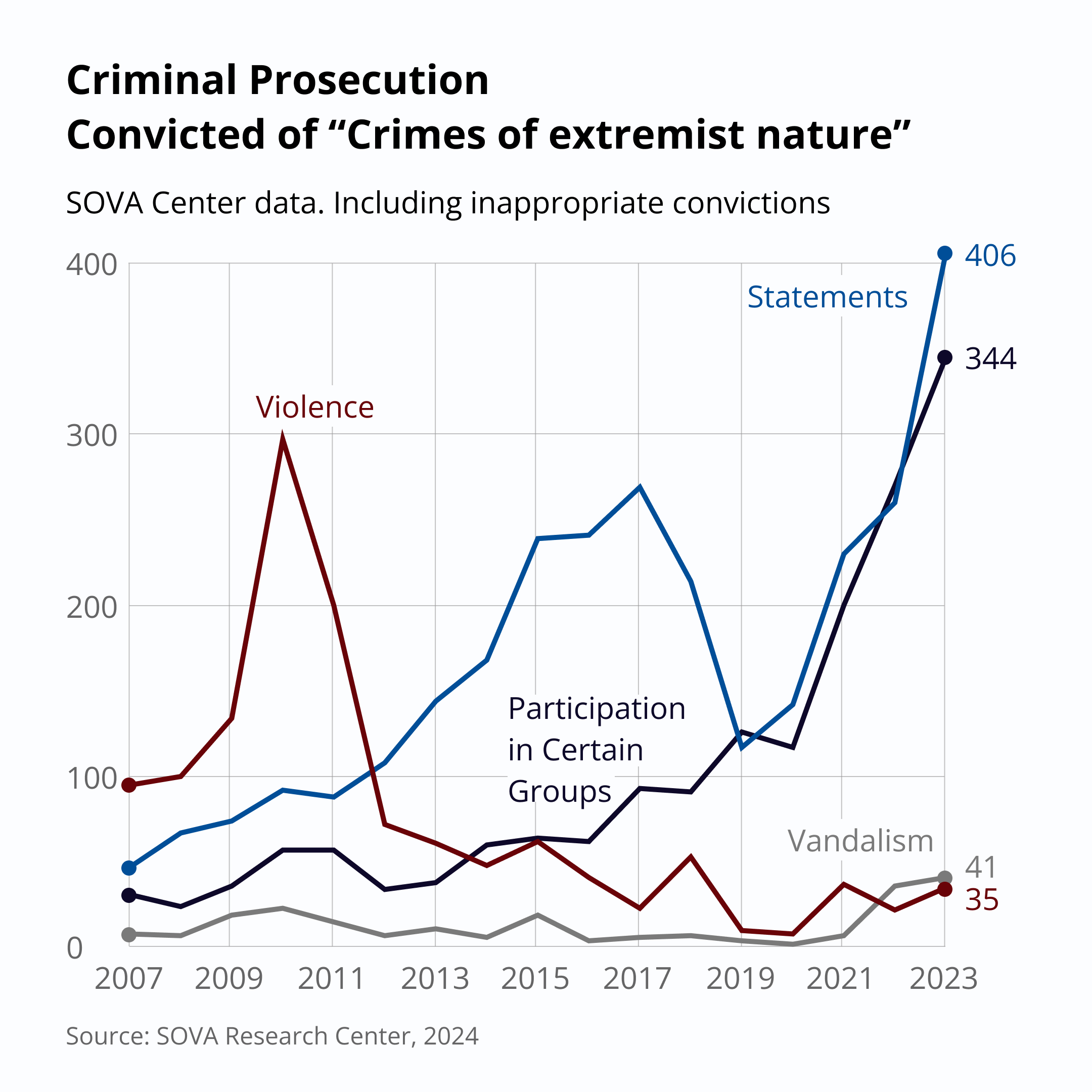

In 2023, the number of sentences for speech increased, although not as drastically as it did in 2022. While convictions for online speech undoubtedly dominate, as usual, 2023 saw a marked increase in the proportion of those convicted for offline acts compared to the previous year: this was mainly due to those convicted for campaigning in prison and for repeated displaying of Nazi symbols, most often their own tattoos. The trends we have been observing since 2021 — growing numbers and political diversity of those convicted under the article for calls for terrorist acts and of those convicted for speaking out against the authorities — have worsened. The penalties became harsher, and the number of those sentenced to imprisonment for statements without circumstances clearly calling for prison time increased.

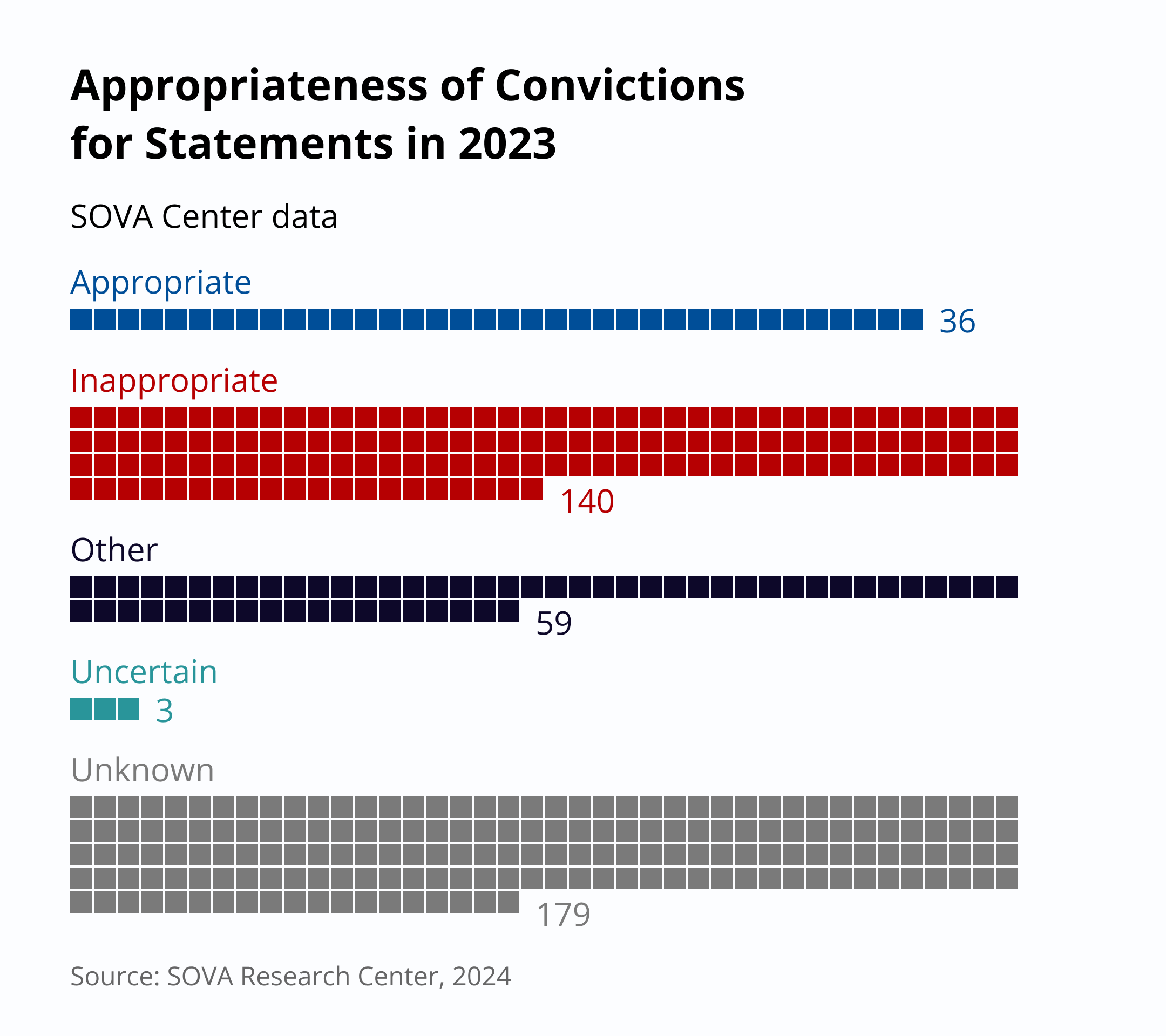

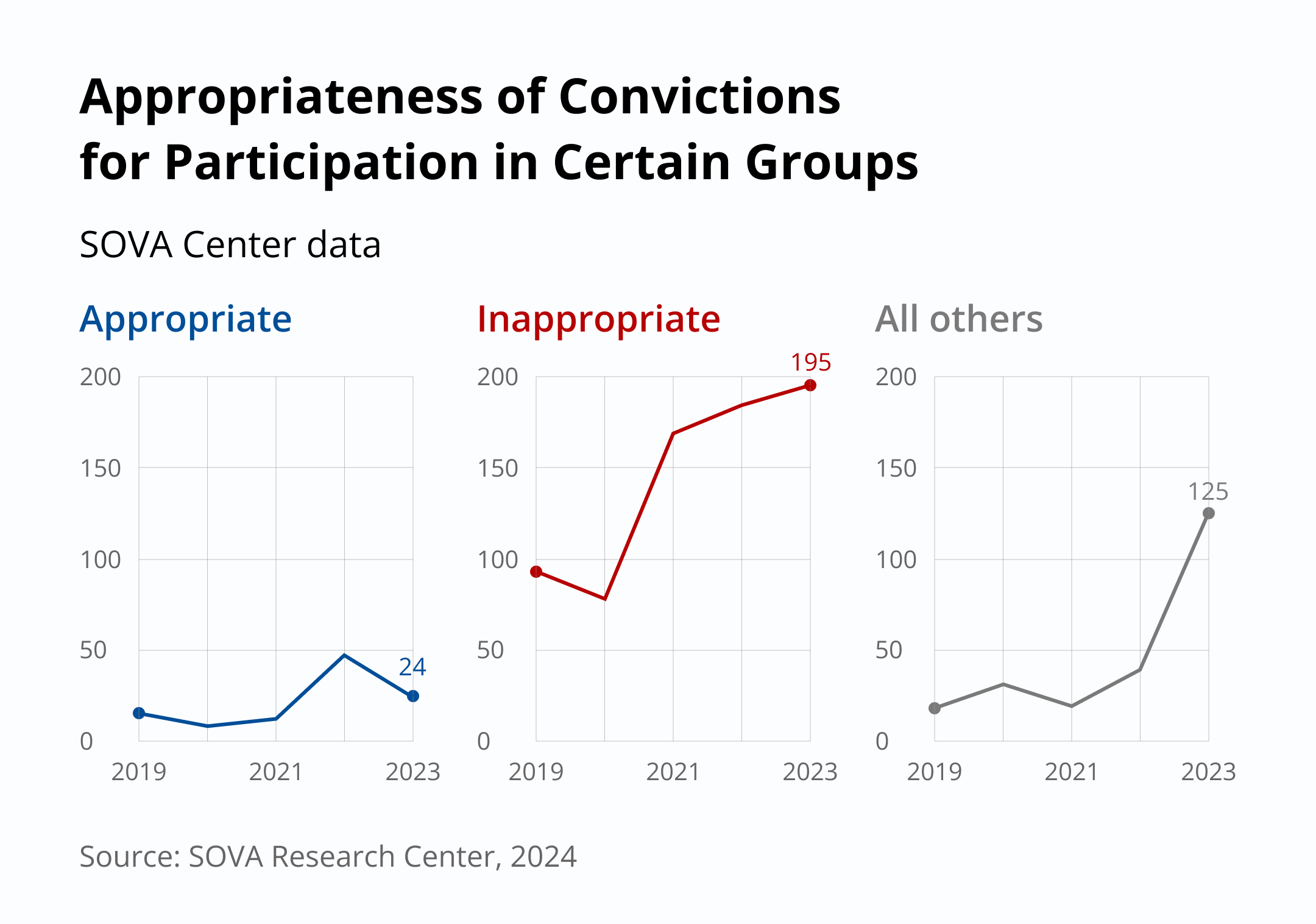

And all this does not include the clearly inappropriate convictions, which in 2023 amounted to an unprecedented 35 % of known decisions (in the past, this number has never risen above 15 %).

This is the second year in a row that we are observing an increase in the number of people convicted for participation in extremist and terrorist communities and organizations of almost all political and even non-political shades: last year, sentences were handed down for involvement in far-right organizations (M.K.U., NORD), “Citizens of the USSR,” the Ukrainian Pravyj Sektor (Right Sector), A.U.E., radical Islamist organizations (ISIS, the Caucasus Emirate, etc.), schoolshooters, leftists, and neo-pagans (Old Believers-Ynglings)..

The list of extremist organizations was not very actively expanded in 2023: three organizations were added, and we can consider the ban of only one of them legitimate. In the first months of 2024, however, the list was expanded to include three more organizations banned last year. The most resonant was the banning of the “International LGBT public movement.”

The expansion of the list of terrorist organizations was similarly not very active: the people-haters’ association M.K.U., two units of Russian citizens fighting on the side of Ukraine (the Freedom of Russia Legion and the Russian Volunteer Corps), as well as the Ukrainian Aidar battalion.

The number of those punished under administrative articles has decreased slightly. However, the law enforcement in this part has already gained momentum, and the number of those punished administratively exceeded 5200, of which almost 4000 were prosecuted for displaying prohibited symbols.

Thus, in general, according to our observations, after a rapid growth in 2022, criminal anti-extremism law enforcement is developing at a much slower pace in 2023, but has not quite stabilized, and is compensating for some slowdown by a greater severity of sentences. As for administrative enforcement, viewed by the authorities more as a preventive measure, it has become slightly less active.

Criminal Prosecution

For Public Statements

By persecution for public “extremist statements” we mean statements that were qualified by law enforcement agencies and courts under Parts 1 and 2 of Art. 148 of the Criminal Code (the so-called violation of the feelings of the believers), Art. 2052 (public calls for committing of terrorist activity or public justification thereof), Paragraph D of Part 2 of Art. 2073 (“fakes” about the army, if the act is motivated by hatred[3]), Art. 280 (calls for extremist activity), 2801 (calls for separatism), 2803 (repeated discrediting of the actions of the army and officials abroad; but the use of this article is wholly unlawful, as well as Art. 2073, as long as it doesn’t involve calls for violence.), 2804 (public calls to carry out activities against the security of the state), 282 (incitement to hatred), 2824 (repeated display of prohibited symbols), and to some extent under Art. 3541 of the Criminal Code (rehabilitation of Nazi crimes, desecration of symbols of military glory, insulting veterans, etc.) — excluding those acts that should have been classified as vandalism (this section of law enforcement is reflected in the two separate reports mentioned above).

This does not comply with the official interpretation of the term[4]. Thus, Article 2052 is categorized as terrorism, but too often it has little to do with terrorism itself, and we consider it within the broader concept of extremism. Articles 148 and 3541 are officially considered “extremist” only when a hate motive is established, but they are so closely related to extremism that we prefer to consider them at all times. Of course, some other articles of the Criminal Code may also be classified as “extremist statements” if a “hate motive” is established as an aggravating circumstance, but we are not aware of any such cases.

Beginning this year, we take a different approach in our reports to accounting for sentences for statements written or drawn on objects and structures. These acts have the characteristics of both public statements and vandalism, and law enforcement in this sense is not always consistent: the same acts (for example, drawing swastikas on the walls of residential buildings or writing slogans on an icebreaker under construction) may be qualified both under Article 214 of the Criminal Code (vandalism) and under articles on statements. So far, we have followed the judicial qualifications, and therefore some of the sentences of similar nature were included into our hate crime reports and some into reports on anti-extremism law enforcement. We have now decided to count all sentences for crimes against property (damage to monuments, various cultural objects and property) as sentences for “vandalism” rather than for public statements, even if the sentence uses one of the CC articles listed above. This change[5] would not affect our statistics for previous years too much: very few such sentences were handed down. For example, in preparing this report, only three sentences were reclassified from “statements” to “vandalism.”

In 2023, according to our incomplete data, the number of convictions for “extremist statements” increased slightly compared to 2022. Sova Center has information about 237 sentences against 283 people in 75 regions of the country[6]. In 2022, there were 214 such convictions against 229 people in 64 regions.

We do not include in this report the sentences that we consider completely unlawful, and they are further excluded from all calculations in this report. Our statistics do not include any acquittals (none are known in both 2022 and 2023). Also not included are court decisions on people sent for psychiatric treatment in cases where criminal prosecution was terminated (in 2023 we know of 12 such decisions, in 2022, of two). For example, the court sentenced reserve colonel Mikhail Shendakov to compulsory treatment under a combination of Articles 280 and 282 of the Criminal Code for publishing a video with calls “to carry out violent actions against law enforcement officers and representatives of the authorities.”

For 2023, we know of cases opened against 326 people, but this data is certainly far from complete.

Overall, we know of only about half of the “extremist statements” cases. According to the data posted on the Supreme Court website[7], in the first half of 2023 alone, 314 people were convicted of “extremist statements,” and this number includes only those for whom this was the main charge[8]. And this is more than the 267 convicted during the same period in 2022[9]. In this report, we use our own data, as the Supreme Court data does not allow for meaningful analysis and is very late.

Since 2018, we have been using a more detailed approach to conviction classification[10].

We deem appropriate those convictions where we have seen the statements, or are at least familiar with their contents, and believe that the courts have passed convictions in accordance with the law. In our assessment of appropriateness and lawfulness, we apply six-part assessment of the public danger of public statements[11], supported by the Russian Supreme Court and the UN Human Rights Council almost in its entirety.

In 2023, we consider 23 convictions against 36 people appropriate (17 convictions against 24 people in 2022). An example of an appropriate verdict is a court’s decision in the Orenburg region against a member of the VKontakte group of the people-haters’ community Maniacs. Cult of Murder (M.K.U.), who posted photos and videos with scenes of beatings and violence against “representatives of other nationalities and religions” and “tried to recruit a minor to the community, ... offering him, as a condition for joining, to commit the murder and record the killing process on video.”[12]

Unfortunately, in too many cases — marked as “Unknown” (167 convictions against 179 people) — we do not know enough or don’t know at all about the content of the incriminating material and therefore cannot assess the appropriateness of the court decisions.

The “Uncertain” category (three verdicts against three people) includes those court decisions that we find difficult to evaluate: for example, we tend to consider one of the episodes of the prosecution as lawful and another as not, or we have reasons to consider the sentence to be unlawful, but there is not enough information to make a confident judgment about it.

The “Other” category (55 verdicts against 59 people) includes sentences under “extremist” articles of the Criminal Code, which we cannot definitely consider unlawful and which cannot be attributed to anti-nationalism and xenophobia. Rather, these sentences were lawful, but in some cases we cannot judge the appropriateness due to a lack of information.

Some sentences may fall into more than one category if different episodes are evaluated differently. So, for example, a conviction may be wrongful on one episode and rightful or “different” on another. In total for 2023, we counted 133 convictions for public statements in 140 people that were wrongful on at least one episode[13].

In the article-by-article analysis below, we rely on the number of convicts who had one or another article of the CC appear in their sentence, whether as a main or supplementary one.

Art. 2052 of the CC (public calls for terrorist activities) overtook the previous leader in convictions, Art. 280 of the CC (public calls for extremist activities).

According to the Supreme Court data, in the first half of the past year, a total of 149 people were found guilty under Art. 280 (161 people in the first half of 2022), and 167 people on Art. 2052 (126 people in the first half of 2022).

According to SOVA Center data, in 2023, Art. 280 of the CC was used[14] in 111 verdicts against 118 people, and in about 50 % of the cases, this was the only charge. In the new cases known to us in 2023, 88 people had this article.

SOVA Center is aware of 105 verdicts on Art. 2052 of the CC against 120 people. In approximately 45 cases, this was the only charge, and in approximately 30 cases it was combined with Art. 280 of the CC. Art. 2052 of the CC was combined with other anti-terrorism articles of the Criminal Code, such as Part 1.1 of Art. 2051 of the CC (involvement in terrorist activities) or Art. 2055 of the CC (participation in the activities of a terrorist organization). In the new cases known to us in 2023, 153 people had this article.

Whereas the article for public calls for terrorist activities was applied exclusively to radical Islamists only a few years ago, in the past three years it has also been used widely, against virtually all types of political groups: radical ultra-rightists, “citizens of the USSR,”[15] representatives of left-wing organizations, liberal-democratic opponents of the authorities, simply opponents of the war, and people whose political views are unknown to us.

Art. 282 of the CC was used in 15 sentences known to us against 26 people. In seven of them, this was the only charge. Among these was, for example, the former hieroschimonk Sergius (Nikolai Romanov) and his assistant Vsevolod Moguchev for distributing videos inciting hatred against Jews, Catholics, and Muslims[16]. The same article was used in the sentences against ultra-right activists from Voronezh and Saratov and an M.K.U. supporter from Orenburg mentioned in the report on hate crimes[17]. In the new cases known to us in 2023, 40 people had this article.

In this report, we note 23 verdicts against 23 people under Art. 3541 of the CC (rehabilitation of Nazism); for 18 of them, this was the only charge. In most cases, these people were convicted of Holocaust denial or anti-Semitic publications justifying Hitler’s extermination of Jews during World War II. For example, Alexei Naumov from St. Petersburg commented on posts in the Rasa (Race) community and referred to texts by Oswald Mosley, the leader of the British Union of Fascists, and Holocaust deniers Robert Faurisson and Ursula Haverbeck. In his comments to the post by the veteran of the nationalist movement Alexander Turik[18] in memory of Yegor Prosvirnin[19], Naumov expressed his approval of the crimes identified by the Nuremberg Tribunal, referred to Hitler’s Mein Kampf, etc.[20] In the new cases known to us in 2023, 31 people had this article.

Part 1 of Art. 148 of the CC (public actions expressing clear disrespect for society and committed for the purpose of insulting the religious feelings of believers) was applied in three verdicts against four people. This article was the only one in the verdict against two teenagers who burned an icon of Anastasia Uzoreshitelnitsa [Deliverer from Bonds] on a bonfire, shouting “Sieg Heil!” and “Glory to Hitler!” and demonstrating a Nazi salute, and then posted the video online, and against a resident of Krasnoyarsk who scattered the remains of mutton in an Orthodox church on the day of Eid al-Adha celebrations[21]. In other cases, it was combined with other “extremist” and “terrorist” articles: Art. 2052 and 282 in one case and Art. 280 of the Criminal Code in another. In the new cases known to us in 2023, six people got this article.

Art. 2824 of the CC (repeated propaganda or public display of Nazi attributes or symbols or the attributes or symbols of extremist organizations) was applied in 20 verdicts against 20 people[22]. The vast majority were convicted under this article for repeatedly displaying their own tattoos with Nazi and other prohibited symbols, including seven with A.U.E. symbols (i.e. criminal tattoos). In the new cases known to us in 2023, 22 people had this article.

Art. 2073 of the CC (the article on “fakes,” where the hate motive is taken into account) was used in six sentences against six people[23]. All cases involved online publications, and in only two cases the article was the only charge. In all cases, we do not know which publications the charges under Art 2073 of the CC were related to, and and we cannot assess the appropriateness of prosecution under this article. In the new cases known to us in 2023, 14 people had this article (we emphasize that often we are simply unable to assess the lawfulness of cases at this stage).

Art. 2804 of the CC (public calls to carry out activities that threaten the security of the Russian Federation) was applied in four sentences against four people. In the new cases known to us in 2023, 11 people had this article.

Just like in 2022, we are not aware of any verdicts or new cases under Art. 2801 of the CC (calls for separatism)[24].

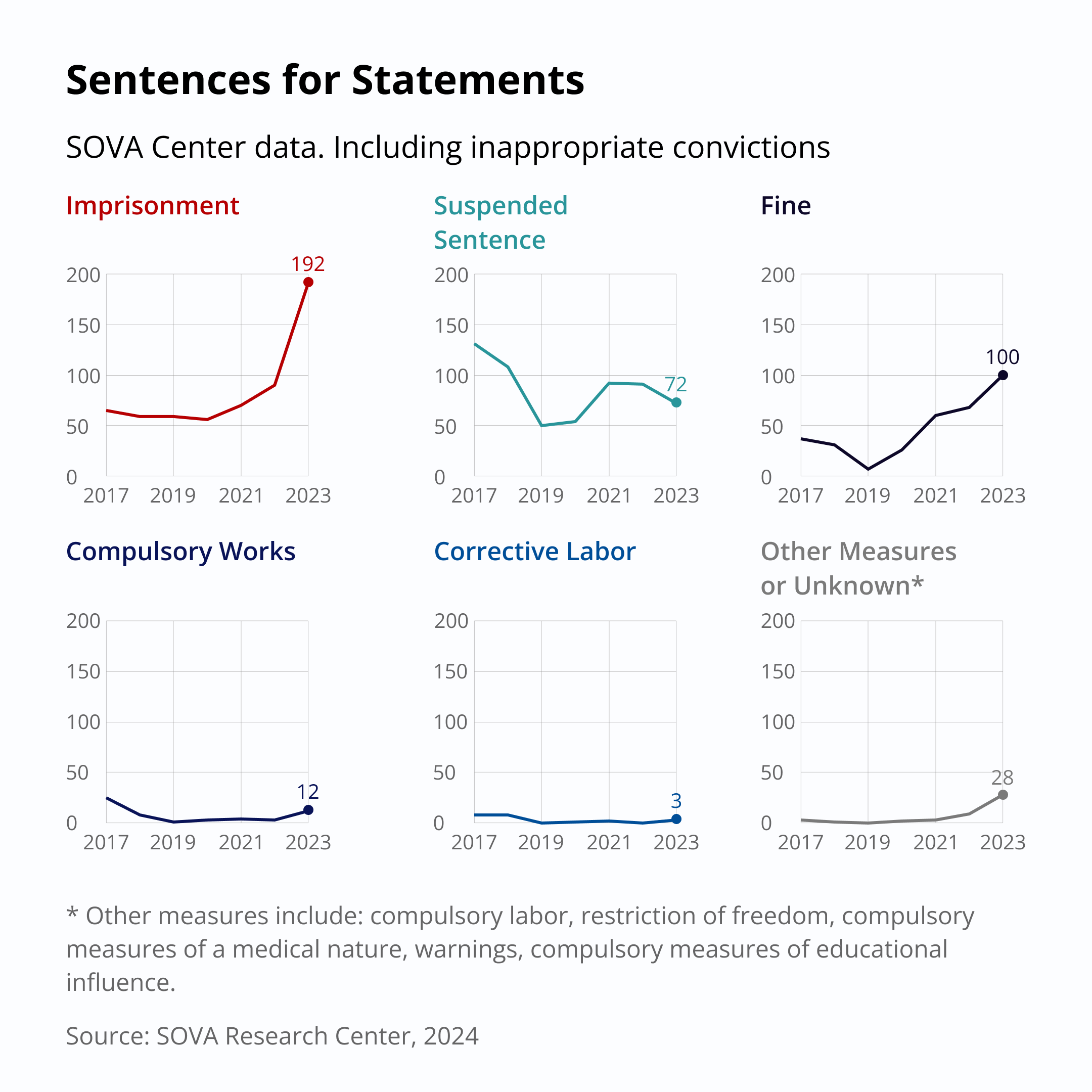

In 2023, penalties for public statements, excluding wrongful convictions, were distributed as follows:

- 133 people were sentenced to imprisonment;

- 65 received suspended sentences without any additional measures;

- 52 were sentenced to various fines;

- 7 were sentenced to mandatory labor;

- 11 were sentenced to forced labor;

- 3 were sentenced to correctional labor;

- 1 was sentenced to correctional labor, suspended;

- 3 were sentenced to the restriction of liberty;

- 1 was found guilty, but no punishment was imposed due to his death.

The case against another person was dismissed due to the expiration of the statute of limitations.

As we can see, the number of those sentenced to imprisonment has significantly increased compared to a year earlier (47 %): in 2022, we reported 71 sentenced to imprisonment (32 %).

Most of them received prison terms in conjunction with charges other than statements. It could have been articles of weapons possession or violence. Some were already serving prison time, and their terms were increased. Some were previously released on parole or were on probation.

However, 30 people received prison terms in the absence of any of the above-mentioned circumstances that reduce the chances of avoiding incarceration (or we just do not know about them). They are listed by article of the CC below.

Art. 280 of the CC: three incarcerated

-A young man from Saratov was sentenced for publishing comments in VKontakte “calling for attacks on residents of the Caucasus and Central Asia” to one year in a strict regime colony and was deprived of the right to engage in activities related to the administration of sites and channels online (hereinafter such restrictions will be referred to as “Internet ban”) for one year.

- Ruslan Fatkhelbayanov from Ufa was sentenced to one and a half years in a penal colony for publishing comments in a Telegram group with “calls for extremist actions against law enforcement officers and the use of weapons”, with an Internet ban and a ban on participation in public events, both for two years.

- A 39-year-old from Astrakhan was sentenced to one year in a penal colony for publishing a post on VKontakte “in which he called for violence against representatives of state authorities

Art. 3541 of the CC: three incarcerated

-20-year-old Nikita Karpov from Omsk was sentenced to one and a half years in a general regime colony with an Internet ban for publishing a post “containing an approving attitude to Nazi ideology” and “false information about memorable dates related to the Great Patriotic War” in one of the social networks.

- In the Leningrad region, A. Yaskovich was sentenced to two years in a penal colony with an Internet ban for publishing texts and photos of Nazi criminals, Nazi symbols, and other materials “with signs of approval of war crimes committed by the leaders of the Third Reich” in the open VKontakte group Dewingston 2.0.

- Igor Veshnyakov, 56, from the village of Palatka in the Magadan region, was sentenced to two years in a penal colony with an Internet ban for publishing a message denying the facts established by the Nuremberg Tribunal in a WhatsApp messenger group.

Art. 2824 of the CC: two incarcerated. Both of them were previously charged with Part 1 of Art. 20.3 of the Administrative Code (propaganda and public display of Nazi symbols).

- In Sochi, a 19-year-old young man was sentenced to 10 months in prison for showing a Luftwaffe Pilot qualification badge and the emblem of the SS tank division Dead Head (Totenkopf) to traffic police officers who stopped him to check his documents, and displaying an image of the flag of Nazi Germany on his phone.

- In Crimea, 53-year-old Vladimir Blagov was sentenced to two years in a strict regime colony for posting eight images with Nazi symbols in a social network.

Art. 2052 of the CC: 13 incarcerated.

They were adherents of a variety of political views: supporters of ISIS, “Citizens of the USSR,” anarchists, opponents of military action in Ukraine, and people whose political views we do not know.- A 26-year-old from Novokuznetsk was sentenced to two years in a general regime colony for comments calling for terrorist activities, including assassinations of officials.

- Syktyvkar resident Vyacheslav Rossokhin was sentenced to two and a half years in a general regime colony with an Internet ban for comments “with public calls for attacks on the life of a Russian public official”.

- A Kazan resident was sentenced to two years in a general regime colony with an Internet ban for disseminating unknown materials in a social network with calls for terrorist activity towards “a group of persons singled out on religious grounds.”

- “Citizen of the USSR” from Orel Ilya Florinsky was sentenced to six years in prison with an Internet ban for his reposts in VKontakte and Telegram[25]of the video “Scheme of liberation from the regime” with calls “for Muscovites to take to the street and seize the Kremlin” and for an anti-vaxxer post.

- O. from Samara was sentenced to two years in a general regime colony with an Internet ban for calling for terrorist activity of unknown content.

- A resident of Novorossiysk was sentenced to two and a half years in a general regime colony with an Internet ban for recording several video messages calling for terrorist activity and posting them in a messenger chat room.

- Anarchist Yaroslav Vilchevsky, 32, from the Far East was sentenced to two years in a general regime colony with an Internet ban for his post about Mikhail Zhlobitsky, who blew himself up in the Arkhangelsk FSB building.

- The leader of a cell of ISIS supporters was sentenced to three years in a strict regime colony with an Internet ban (region unknown).

- A resident of the Astrakhan region received two years in a general regime colony for posting public calls for terrorist activity “against those who do not profess Islam” in a popular social network.

With the beginning of the conflict in Ukraine, more publications with calls for violent actions against the Russian authorities appeared in the Russian Internet. Consequently, the content of the materials that attracted the attention of law enforcement became harsher, and the number of people imprisoned under Article 2052 of the Criminal Code for statements in connection with the special military operation increased.

- Monk of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad (ROCA)[26] Ilarion (Nikolay Shatkovsky, the Belgorod region) was sentenced to five years in a general regime colony with an Internet ban for publishing posts supporting Ukraine. We do not know which of his statements led to the criminal case, but in a video available on TikTok, the monk addresses Russians, blames the war on the “demon” Putin and his “team of Yid-demons oligarchs” and calls not only to “criticize” the president, but also to “kill.”

- A native of the city of Ukhta (the Komi Republic) was sentenced to five and a half years in a penal colony for calling on social media to set fire to military enlistment offices and commit other sabotage.

- A 20-year-old student of Balakhta agricultural college(Krasnoyarsk Krai) was sentenced to two years in a general regime colony for creating a Telegram channel where he published calls for arson and bombing of government buildings and attacks on law enforcement officers, as well as instructions on how to make explosives and information on methods of conspiracy and personal security.

- Andrey Anfalov from Nizhny Novgorod was sentenced to five and a half years in a general regime colony with an Internet ban for posts on his Odnoklassniki page calling for arson attacks on military recruitment centers and “attempts on the life of one of the Russian public officials.”

Seven people were convicted under a combination of Art. 280 and 2052 of the CC.

- A. Autlev from Adygea, was sentenced to five and a half years for propaganda of the activities of the “Islamic State” and calls “to commit crimes against law enforcement officers and persons who do not profess Islam.”

- Denis Anokhin from the Tula region received a four-year prison sentence with an Internet ban for publishing comments in VKontakte calling for violence against the military, urging people not to go to the military recruitment centers and to avoid serving in the army.

- A Tomsk resident got two years in a general regime penal colony with an Internet ban for calls in social networks “to commit crimes against state and religious figures.”

- A resident of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky was sentenced to four years in a general regime colony with an Internet ban for publishing texts in VKontakte about “the need to kill Russians and representatives of the authorities.”

- A resident of Novy Urengoy (Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous District) was sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment for publishing texts, photos, and comments of unknown content with approval of violence on social networks, with the first three years to be served in prison and the rest in a general regime penal colony.

- A resident of Kansk, Krasnoyarsk Krai, was sentenced to seven years in a special regime colony for calling for violence against Russians and for blowing up the Crimean bridge.

- Igor Orlovsky from Krasnoyarsk received three years in a general regime colony with an Internet ban for comments on social media calling for the killing of “Russian occupiers” and for world peace (cessation of war), as well as for the assassination of Vladimir Putin, whom he called an “old fascist.”

In all of these cases, we cannot assess the “words-only” sentences as wrongful because the publications clearly contained calls for violence. However, we doubt that the courts properly assessed the degree of public danger of these calls in all cases.

With regard to Art. 2804 of the CC, we know of two such convictions

- Parvinakhan Abuzarova from Tatarstan was sentenced to three years in a general regime colony for posting on social media “calls on the Russian servicemen taking part in a special military operation in Ukraine to desert.”

- Sergei Korneev from Miass, the Chelyabinsk region, was sentenced to two years in a general regime colony for calls in one of the social networks “to sabotage mobilization and military activities, as well as to damage military equipment and weapons.”

Prior to 2021, we did not include in our calculations those convicted to imprisonment under Art. 2052 of the CC as “terrorist,” since we believed that the penalties under the anti-terrorism article were traditionally more severe and our knowledge of the specific content of cases was always limited; additionally, prior to 2018, the vast majority of sentences under Art. 2052 of the CC had nothing to do with countering incitement to hatred. In 2021 and 2022, we counted and described those sentenced to incarceration under this article alone (without additional circumstances) separately from the others. However, as we have already written above, law enforcement under this article is expanding, and now it is not that different from law enforcement, say, under Art. 280 of the Criminal Code, often both of these articles are imputed simultaneously, so we decided to count those convicted under Art. 2052 of the CC together with all the others. To ensure the comparisons with previous years are correct, we calculated the 2021-2022 data in the same way.

Compared to previous years, enforcement has become tougher in this sense: in 2022, we reported 16 such convictions, and 22 in 2021. But if we look at percentages, we cannot say that this parameter shows any stable dynamics: in 2023, the share of those sentenced to imprisonment “for words only” without circumstances clearly implying imprisonment amounted to 10.9 %, in 2022 — 7 %, in 2021 — 10.6 %.

In 2023, the share of suspended sentences decreased from 36 % (in 2022) to 23 % (65 out of 281). The share of the remaining convicts sentenced to punishments involving neither real nor suspended imprisonment, i.e. mainly fines, was 27.4 %, practically the same as the 27.5 % in 2022.

Almost all sentences mention additional bans on activities related to the administration of Internet sites, bans on publications on the Internet, or on the use of the Internet in general.

As has become a tradition, the overwhelming majority of convictions were for materials posted online — 190 out of 237. However, the share of such materials has been decreasing for the second year in a row and amounted to 80 % (88.5 % in 2022, 91 % in 2021).

As far as we were able to understand from the reports of the verdicts, these materials were posted on (possibly more than one):

- social networks — 124 (55 on VKontakte, 2 on Facebook, 2 on Instagram, 2 on TikTok, 3 on Odnoklassniki, 60 on unspecified social networks);

- instant messenger groups and channels — 33 (27 in Telegram, 2 in WhatsApp, 1 in Discord, 1 in Viber, 2 in unspecified messengers);

- YouTube — 5;

- unspecified online resources — 35.

The types of content are as follows (different types of content may have been posted in the same account or even on the same page):

- comments and remarks, correspondence in chats — 71,

- other texts — 42,

- videos — 24,

- films — 2,

- images (drawings and photographs) — 15,

- audio (songs) — 3,

- administration of groups and communities — 2,

- unspecified — 55.

As for placement, little changed over the past 10 years (see previous reports on this topic, as well as reports on prosecuting online extremism in the 2010s[27]): law enforcement monitoring remains focused on social media; the share of cases for publications in messengers increased, however. In terms of genre distribution, the trend observed since 2020 continues[28] — sentences are more often handed down “for words” in the literal sense, that is, mostly for comments and remarks, although as recently as 2019 the bulk of sentences were handed down for videos and images[29].

The number of convictions for offline statements turned out to be twice as high as a year earlier: 47 convictions for 66 people, compared to 24 convictions for 31 people in 2022.

Sentences were imposed for the following offline acts:

- agitation in prison — 19 (28 people);

- repeated demonstration of tattoos with Nazi symbols and symbols of the A.U.E. or Ukrainian nationalist organizations banned in Russia — 13 (16 people); including repeated demonstration of tattoos in prison or colony — 6 (7 people);

- posting stickers and leaflets — 8 (8 people);

- to a far-right group for unknown episodes of propaganda — 1 (7 people);

- shouts during attacks — 1 (2 people);

- demonstration of prohibited symbols to traffic police officers — 1 person;

- verbal threats with shaking a bat — 1 person;

- agitation in college — 1 person;

- appearance on Ukrainian television — 1 person;

- private conversations with colleagues — 1 person.

As can be seen, the introduction of Art. 2824 of the CC contributed significantly to our statistics with convictions for repeated display of tattoos. Previously, such acts entailed only administrative liability. These demonstrations occurred also in places of detention. We find criminal prosecution for such acts questionable: it is not always possible to avoid displaying an existing tattoo, for example while changing clothes or in the shower. And it is difficult to remove or change tattoos in places of detention.

In general, the proportion of people sentenced for acts committed in places of detention has increased significantly compared to 2022. This is especially evident in the increased number of people punished for verbal agitation in prisons. The prison environment is quite closed, and we rarely know the details of such cases. We have repeatedly noted that we have doubts about such sentences[30]. It is true that there is a significant proportion of people who are prone to violence among prisoners, so radical agitation (whether jihadist or far-right) in this environment is always dangerous. But the key criterion of the size of the audience remains unclear in cases of public statements: for example, it is unlikely that a conversation in a narrow circle of cellmates can be considered public.

By the same criterion of audience size, we are inclined to recognize as legitimate the sentences for shouts during attacks, for realistic threats, for stickers and leaflets posted on street light poles (leaving aside the content). But we do have doubts about the sentence imposed for a private conversation with colleagues.

We often do not have access to the materials that became the subject of legal proceedings, so as far as the content of statements is concerned, in many cases we are forced to focus on the descriptions of prosecutors, investigative committees, or the media, although these descriptions, unfortunately, are not always accurate, and in some cases they simply do not exist. Therefore, we can conduct an analysis of the direction of incriminated statements only for some of the cases we are aware of.

We identified the following targets of hostility in the sentences passed in 2023 (some of the incriminated materials expressed hostility toward more than one group):

- ethnic enemies — 54, including: Jews — 15, Russians — 7, natives of the Caucasus — 8, natives of Central Asia — 4, Sinti and Roma — 2, Poles — 1, non-Slavs in general — 2, Iranians and their sympathizers — 1, unspecified ethnic enemies — 14;

- religious enemies — 32, including: Orthodox Christians, including priests — 3, Jews — 2, Catholics — 2, Muslims — 3, infidels from the Islamic point of view (romanticizing militants, calls to join ISIS and jihad) — 17, unspecified religious enemies — 5;

- representatives of the state — 134, including: the state and the authorities in general — 59, FSB officers — 4, police officers — 5, law enforcement officials in general — 19, military — 33, president personally — 9, MPs — 2, government officials in general — 2, head of the Komi Republic — 1;

- residents of the LPR and DNR — 1;

- Russians and all those who support the special military operation — 5;

- low-level government employees, perceived as officials — 3, including: employees of the housing and utilities services — 1, healthcare professionals — 1, municipal officials — 1;

- schoolchildren (related to the Columbine movement) — 1;

- unspecified object of hostility expressed through the display of Nazi symbols and portraits of Nazi leaders — 23;

- completely unknown — 44.

According to our estimates, at least 70 convictions in 2023 were for statements related to military conflict in Ukraine (or approximately 30 % of those included in this report).

In the past three years, the three main groups of enemies — ethnic, religious, and state representatives — remain the same. The share of representatives of state authorities again increased significantly and amounted to 56.5 % (in 46 % of sentences in 2022 and 41 % in 2021).

For Participation in Extremist and Terrorist Groups and Banned Organizations

The number of those convicted for participation in extremist and terrorist communities and organizations increased again. In 2023, we have information about 92 verdicts against 149 people under articles 2821 (organizing, recruiting, or participating in an extremist community), 2822 (the same for a banned extremist organization), 2054 (the same for a terrorist community, excluding recruitment), 2055 (the same for a banned terrorist organization), and 2823 of the CC (financing of extremist activities). This is twice as high as in 2022 (47 convictions against 85 people). These numbers do not include inappropriate convictions, whose number in the past year was again much higher than in other categories: we have deemed unlawful 90 verdicts against 195 people[31] (all of the convictions known to us under Art. 2823 were unlawful). In 2023, we know of 60 new cases, but this data is far from complete.

According to the Supreme Court data[32], 271 people were convicted under these articles, if we count only the main charge, in the first half of 2023 alone[33] (430 in the entire 2022). Thus, assuming that such sentencing continued with the same intensity in the second half of the year as in the first half, the number of convicts in this category increased by almost a third again, but there are usually more convictions in the second half of the year than in the first.

According to our data, out of the total number of convicted persons, the share of those convicted for involvement in ultra-right organizations was 13,4 % (20 out of 149), in the “Citizens of the USSR” organizations — 12,8 % (19), in Pravyj Sektor and other banned Ukrainian organizations — 14,8 % (22), in A.U.E. — 38,9 % (58), in radical Islamist organizations and groups — 14 % (21), in others — less than 1 %: 2 in the Columbine movement, 1 in left-wing organizations, 1 in the Old Believers-Ynglings[34], in organizations unknown to us — 3 % (5).

According to our data, in 2023, Art. 2821 of the CC was applied in 12 convictions against 23 people. In the new cases known to us in 2023, 17 people got this article.

This article has traditionally been applied primarily to members of far-right groups.

Some of them were already mentioned in our report on hate crimes[35] and in this report. Among them are: members of an ultra-right group from Voronezh, who received suspended sentences; a 19-year-old M.K.U. member from the Orenburg region, who received 17 years in prison; a member of an ultra-right group from Kazan, who received four years and 10 months in a penal colony; members of an ultra-right group from Belgorod, who received suspended sentences; and ultra-right activists from Saratov, who were detained during the hunt for M.K.U. members and received sentences ranging from two and a half years in a general regime colony to 10 months in a penal colony.

Below we list other far-right activists convicted of participation in an extremist community.

- Kirill Vasyutin and Dmitry Lobov from Omsk were sentenced to prison time for creating a group People’s Association of Russian Movement (NORD) on VKontakte and publishing materials promoting right-wing radical ideology, calling for the use of violence, and “justifying fascism.” The participants planned attacks on people of non-Slavic appearance, natives of Central Asia and the Caucasus, anti-fascists, and LGBT people. At least one street attack is known to be committed by members of the group on a random person, motivated by ethnic hatred. During the investigation, items depicting swastikas, a gas gun, folding knives, brass knuckles, bats, and gas and pepper spray were seized from the organizers and members of the group.

- Maxim Tikhomirov, 18, tried to create an ultra-right-wing group in Novorossiysk and received a three and a half year general regime colony. According to the prosecutor’s office, he created a group with five members in one of the messengers; the group published materials about “preparing xenophobic attacks motivated by hatred and actions against the current government.”

In addition, in the Volgograd region, participants of one of the numerous organizations of “Citizens of the USSR,” and in Moscow, Alena Krylova, a defendant in the Left Resistance case, were sentenced to imprisonment under Article 2821.

According to our data, Art. 2822 of the CC was used in 65 verdicts against 105 people. In the new cases known to us in 2023, this article appeared in 32 people. The composition of the groups of those convicted under this article is almost identical to that of last year.

As has become customary, members of the banned “Citizens of the USSR” have traditionally been actively persecuted under this article. According to our data, at least 16 people from Moscow, the Bryansk region, Dagestan, Karachay-Cherkessia, Kirov, Krasnoyarsk, Altai Krai, and Khakassia were found guilty of membership in these organizations. 11 of them were sentenced to imprisonment in a high-security colony, and five received suspended sentences.

18 people in Moscow, Adygea, Stavropol Krai, Karachay-Cherkessia, and in the Kursk, Lipetsk, and Rostov regions were convicted of involvement in Pravyj Sektor (Right Sector). Seven of them were already in custody. Some of the convicts were sentenced to imprisonment on charges of intending to travel to Ukraine to join Pravyj Sektor, others — on charges of recruiting into Pravyj Sektor, including in places of detention, and others were charged with creating propaganda materials, taking the oath, and preparing terrorist attacks.

Five people in Dagestan and the Ivanov and Rostov regions were sentenced to imprisonment for involvement in the activities of the radical Islamist organization Takfir Wal-Hijra. Although the organization by that name has long ceased to exist, there have indeed been and probably still are followers of some of its ideas in Russia; we are unable to assess the extent of their radicalism and the content of their actual activities.

58 people across the country were found guilty of participating in AUE., recognized as extremist[36], although there is no doubt that no such organization exists, and all we can talk about is not even a subculture, but a brand used to exploit the romanticization of crime[37]. The vast majority of them had already been in prison, and had to serve additional prison time. It seems that often these are not A.U.E. leaders, but organizers or active participants of criminal communities.

Additionally, a former deputy of the Ostrov settlement of the Pskov region, a supporter of the Ancient Russian Yngliist Church of the Orthodox Old Believers-Ynglings, a neo-Pagan association banned in Russia back in 2004, was sentenced to imprisonment; he posted videos of this organization on YouTube.

In 2023, we know of seven people convicted under Art. 2054 of the CC. All of them were already in custody and were convicted of involvement in a radical Islamist organization. All seven also had Art. 2052 of the CC in their verdicts. We are not aware of any new cases under Art. 2054 of the CC in 2023.

We are aware of nine convictions of nine people under Art. 2055 of the CC. They were sentenced to imprisonment for their involvement in a neo-Nazi organization NS/WP (National Socialism / White Power), jihadist organizations (ISIS, Katibat al-Tawhid wal-Jihad — 6 people), and the subculture of schoolshooting (the Columbine movement — 2 people). In the new cases known to us in 2023, eight people had this article.

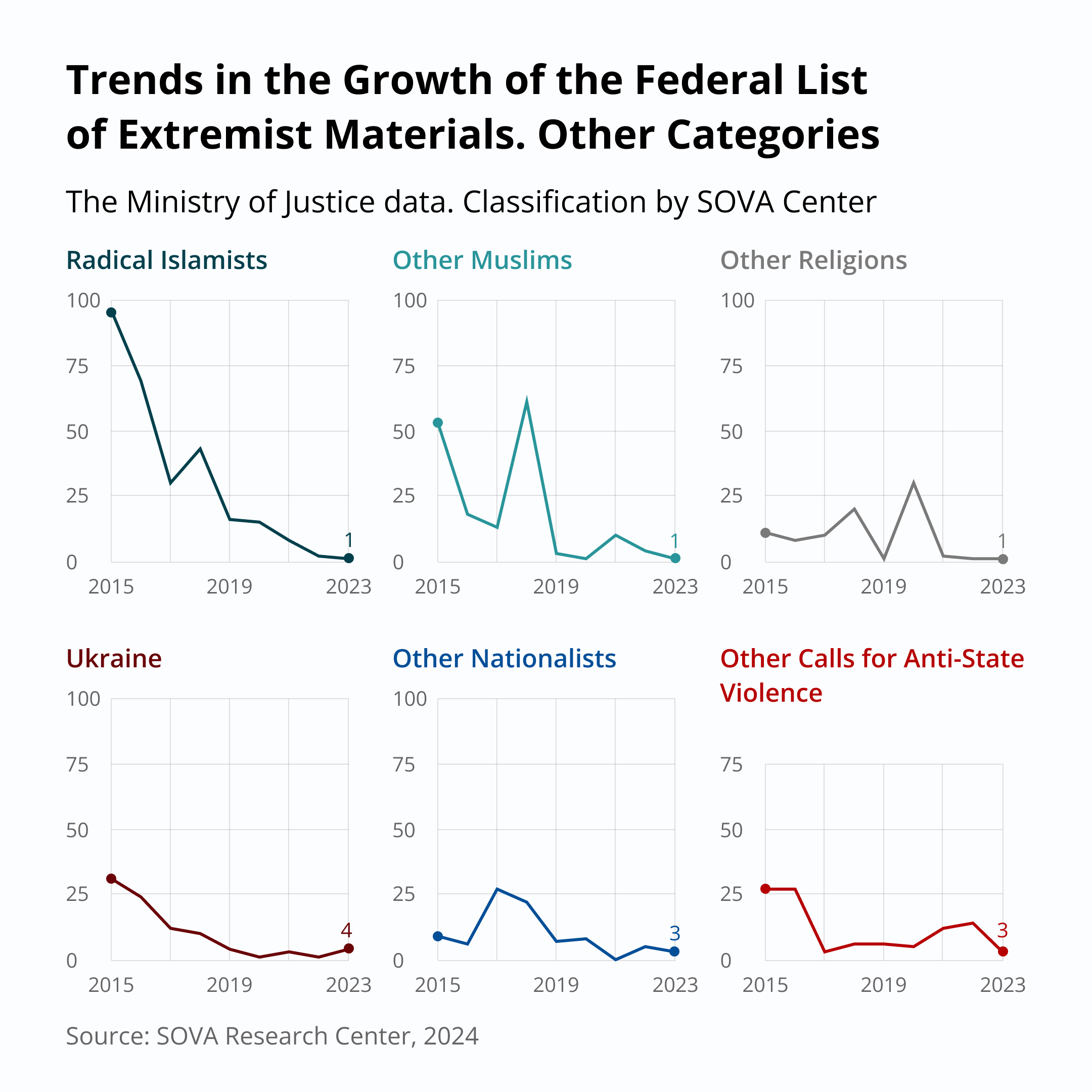

Federal List of Extremist Materials

In 2023, the growth rate of the Federal List of Extremist Materials remained approximately the same as a year earlier: the list was updated 28 times with 82 entries (81 in 2022). As of March 4, 2024, the number of entries on the list has reached 5417.

New entries fall into the following categories:

- xenophobic materials of contemporary Russian nationalists — 41;

- materials of other nationalists — 3;

- materials of Orthodox fundamentalists — 8;

- materials of Islamic militants and other calls for violence by political Islamists — 1;

- other Islamic materials — 1;

- materials by other peaceful worshippers (writings of Jehovah’s Witnesses) — 1;

- peaceful opposition websites — 2;

- materials from the Ukrainian media and the Internet — 2;

- extremely radical speeches from Ukraine (usually far-right) — 2;

- other anti-government materials inciting riots and violence — 3;

- works by classical fascist and neo-fascist authors — 2;

- parody banned as serious materials — 2;

- A.U.E. materials — 1;

- people-haters’ materials — 2;

- fiction — 3;

- Citizens of the USSR’s materials — 8.

- people-hate movement M.K.U., repeatedly mentioned in this and previous reports (also known as Maniacs. Cult of Murders, Youth that Smiles [abbreviated as M.K.U.]), declared terrorist by the Supreme Court in January[46];

- two units of Russian volunteers fighting on the side of Ukraine: The Freedom of Russia Legion[47], declared terrorist by the Supreme Court on March 16, and the Russian Volunteer Corps (RVC)[48], declared terrorist on November 16 by the 2nd Western District Military Court;

- The Ukrainian assault battalion Aidar, recognized as terrorist by the Southern District Military Court on September 25.

- ethnic “others” — 285 (including the natives of Central Asia — 54, natives of the Caucasus — 52, Jews — 39, Russians — 39, Sinti and Roma — 11, dark-skinned people — 10, Ukrainians — 5, non-Slavs in general — 6, other ethnic groups — 69);

- religious “others” — 18 (Jews — 3, Muslims — 6, Christians, including ministers of the Orthodox Church — 7, “infidels”, that is, those who do not profess Islam — 1; Buddhists — 1);

- representatives of the state — 51 (police and the siloviki — 23, military — 2, representatives of the authorities, including government officials and deputies of the State Duma — 16, President of the Russian Federation personally — 4, bailiffs — 1, other government officials — 5);

- citizens of the Russian Federation — 6;

- anti-fascists — 2;

- communists — 1;

- other “social groups” (for example, veterans, defenders of the Fatherland, residents of Moscow, women, men, children) — 26;

- unknown — 68.

- Nazi Germany or neo-Nazi Germany (runes, etc.) in various contexts — 568;

- Al-Qaeda, ISIS, the Caucasus Emirate, and other banned Islamist groups — 41;

- Azov and other banned Ukrainian organizations (including slogans) — 38;

- pagan — 19;

- other — 9;

- unknown — 38.

- materials of Russian nationalists — 72 (including songs popular among Russian nationalists, such as the Kolovrat band, or racist videos with scenes of violence — 8);

- books by the leaders of Nazi Germany — 3;

- Islamist materials — 15 (including materials of militant Islamic groups and songs by the bard of the armed Chechen resistance, Timur Mutsuraev);

- Ukrainian materials — 6.

As in previous years, half of the new entries are materials by Russian nationalists. At least 67 of the new 82 entries are online materials: video and audio clips and various texts. Offline materials include books by Russian, Ukrainian, and other nationalists, and Islamic literature. However, sometimes the materials are described in such a way that it is completely unclear whether they were published online or offline. The slowing down of the process of adding new entries to the list does not reduce the number of errors of all kinds, which we mention every year.

As usual, some of the newly added materials were declared extremist clearly unlawfully and inappropriately; their number is slightly higher than in 2022: 13 compared to 8[38].

Banning Organizations as Extremist and Terrorist

Lists of extremist and terrorist organizations were expanding at a far slower rate than the year before.

In 2023, three organizations were added to the Federal List of Extremist Organizations, published on the website of the Ministry of Justice (13 in 2022).

At least in part, the ban on yet another organization of “Citizens of the USSR” can be considered legitimate: The Supreme Council of the Tatar Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (The Supreme Council (VS) of the TASSR, The Supreme Council of the Tatar ASSR/RSFSR/USSR), was recognized as extremist on February 1, 2023, by the Supreme Court of Tatarstan. This group was headed by Tatyana Loskutnikova from Kazan, who said in court that the VS TASSR was “recreated” on August 6, 2019 and dissolved on April 8, 2022. But the court decided that VS TASSR continued its activities after that date. According to the Sova Center, Loskutnikova’s structure was part of Valentina Reunova’s Supreme Council of the USSR, and after its split in the spring of 2020, it became part of another Supreme Council of the USSR, headed by Marina Pugacheva, Elena Tomenko, Olga Reichert, and others. The activities of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR were mainly limited to sending letters to the Russian authorities and holding various congresses and disputes over who and how should dispose of the money of the “recreated” USSR in the future. This movement was not known to be violent. However, some of Loskutnikova’s appeals contained anti-Semitic statements[39].

We consider unlawful and inappropriate the inclusion on the list of the Vesna (Spring) movement, recognized as extremist by the St. Petersburg City Court on December 6, 2022, and the Congress of the Oirat-Kalmyk People, recognized as extremist by the Supreme Court of the Republic of Kalmykia on August 23, 2023[40].

The landmark event of the past year was the recognition by the Supreme Court on November 30, 2023 of “International LGBT public movement” as an extremist organization. The movement was included in the list of extremist organizations on March 1, 2024. We believe that the ban on the LGBT movement is a clearly discriminatory measure, since it deprives a part of society of the opportunity to defend their rights and peacefully express their views[41].

On October 16, 2023, the Central District Court of Khabarovsk recognized the Public Association Ethnic National Association (ENO, E.N.O.) as an extremist organization. According to some reports, the association was created by former activists of the National Socialist Society[42] and participants of other far-right groups. Photos and videos of the group’s “direct action” with attacks on Roma, LGBT people, arson attacks on various public buildings and structures, and acts of desecration of monuments to Holocaust victims periodically appeared on the organization’s platforms. The police believe that Yevgeny Manyurov, who opened fire outside the FSB building at Lubyanka Square on December 19, 2019, and was behind the thwarted attempt to blow up a mosque in Barnaul in 2021, is associated with ENO[43]. The organization was included in the list on February 29, 2024.

On December 7, 2023, the Krasnoyarsk Regional Court recognized another organization of “Citizens of the USSR,” the Executive Committee of the Council of People’s Deputies of the Krasnoyarsk Territory, as extremist[44]. The organization was added to the list on February 1, 2024.

Thus, as of March 4, 2024, the list included 107 organizations[45], whose activities are prohibited by court and their continuation is punishable under Art. 2822 of the CC.

The list of terrorist organizations, published on the website of the FSB, was updated in 2023 with four organizations (seven in 2022). Thus, the list now has 50 organizations.

The list was updated with:

Prosecution for Administrative Offences

We classify several articles of the Administrative Code as “anti-extremist”: Art. 20.3 (display of prohibited symbols), 20.29 (distribution of prohibited materials), 20.3.1 (incitement to hatred), 20.3.2 (separatism), Parts 3-5 of Art. 20.1 (indecent statements about the authorities and symbols of the state), 13.48 (equating Stalin’s crimes with those of Hitler), as well as articles 20.3.3 (discrediting the actions of the army and officials abroad) and 20.3.4 (calls for sanctions against Russia)[49] introduced in 2022. However, we categorize the application of the last four articles as entirely unlawful[50], and our data in this report, including when analyzing articles of the Administrative Code, exclude unlawful and inappropriate decisions.

Thanks to cooperation with OVD-Info, for the second year, we have been using a better method of finding decisions on the Administrative Offenses Code on the courts’ websites, which could not but affect the effectiveness of our data collection. However, we managed to process about a third of the decisions made during the past year. According to the Supreme Court, if we assume that the enforcement in the second half of the year was the same as in the first half, and according to the OVD-Info parser, there was a slight decrease in the number of people punished under all the articles of the Administrative Code considered in this report[51].

It should be mentioned that we cannot fully compare the data for 2022 and 2023, but we can do it approximately. We have the Supreme Court data for 2022, which are calculated according to decisions that have already entered into force (that is, after an appeal, if there was one). For 2023, we have this data for the first half of the year, which can be doubled, and the data from the OVD-Info parser for the whole year (available as of the beginning of March 2024), but according to the decisions of the courts of first instance.

About 1200 decisions came into force in 2022 under Article 20.3.1 of the CAO. Unfortunately, it is impossible to give a more precise number, because starting in 2022 the Supreme Court has combined the data under Articles 20.3 and 20.3.1, but we have determined the approximate ratio based on our data and that of OVD-Info. In 2023, it seems that fewer than 900 sentences were imposed under this article.

In 2023, SOVA Center considered 328 sentences under this article.

The vast majority were punished for publications on social networks, primarily on VKontakte, but also on Odnoklassniki, Instagram, TikTok, Telegram, WhatsApp, (messages in a large group), Pikabu, and YouTube.

Incriminating comments, remarks, videos, and images on the object of hostility referred to:

That is, the trend of the previous year continues: administrative prosecution for inciting hatred, unlike criminal, is mainly applied to ethnoxenophobic statements; anti-state statements are still in second place, with almost a sixfold margin, and statements related to religion take third place.

25 people were punished for offline acts (9 in 2022).

- Alexander Yakovlev, the editor-in-chief of the Yakut newspaper Tuimaada, and Yuri Mekumyanov, the author of two articles published in that newspaper, were sentenced to fines. In the articles written in the Yakut language, linguistic examination found statements containing a negative assessment of Russian people and the Russian language and saw “signs of the putting one or more languages over another... through the open, as well as indirect belittling of language and culture, and through them ... the Russian people.”

- A colony inmate received administrative arrest for encouraging other prisoners to beat and even kill Federal Penitentiary Service (FSIN) officers.

- The rest were punished for xenophobic insults and shouts (directed at Russians, natives of the Caucasus and Central Asia, and “non-Russians” in general) in public places (on the bus (to the ticket controller), on the street, from the balcony of the house, in the hospital, in a hotel, in a store).

Most of those charged under this article were fined between 10000 and 20000 rubles. 24 people were placed under administrative arrest for between three and 15 days. 18 were sentenced to mandatory labor. One person received a warning.

According to the Supreme Court, a little more than 4,000 decisions under Article 20.3 of the CAO came into force in 2022. Unfortunately, for the above-mentioned reason, it is impossible to give a more precise number. In 2023, there were probably about 3900 such sentences.

We analyzed 683 cases (10 of them against minors).

Punishments were imposed under Article 20.3 of the CAO for posting the following materials with symbols on social networks (VKontakte, Odnoklassniki, Instagram, My World) and Telegram and WhatsApp messengers (in some cases, symbols from two categories were present):

250 people were punished for offline acts (203 in 2022).

Among them are 179 cases of punishment for displaying one’s own tattoos with Nazi symbols. 72 out of 179 were inmates of the colonies (in addition, some prisoners did not have tattoos, but other objects with Nazi symbols such as pendants and cards). The rest showed off their tattoos beyond prison walls, for example, at football matches or in the park.

Nine people did a Nazi salute or shouted “Sieg Heil!” in public places, 12 people were prosecuted for painting graffiti and three for pasting stickers with Nazi symbols on the facades of residential buildings, five people displayed on their clothes, three hung it in dorm rooms, five pasted it on their own vehicles, and three people were punished for selling items (hats and belts) with Nazi symbols. One person arranged flower beds in his garden in the shape of a swastika. One person turned on an audio recording of Hitler’s speech in German using a loudspeaker at a railway station. Another set the Nazi march as a ringtone in his mobile phone. The last examples illustrate the blurring of the notion of what can be considered “symbols and attributes,” as stipulated by the law. In addition to the above, six people pasted leaflets with the symbols of the Ukrainian Pravyj Sektor and the Freedom of Russia Legion, both banned in Russia. Another emailed a letter with the symbols of the Volunteer Rukh [Movement] of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, addressed to the magistrate.

Most of the offenders under Article 20.3 were fined between 1000 and 3000 rubles. 127 people were sentenced to administrative arrests (between three and 15 days), one person was sentenced to compulsory labor, and one person also received a warning. In several cases, confiscation of items of an administrative offense (clothes, a drum, a mobile phone) was reported.

According to the Supreme Court, in 2022, 869 decisions under Art. 20.29 of the CAO came into force. Official data for the first half of 2023 lists about 440 such decisions, but the OVD-Info parser has only about 370, so probably the actual number is between 400 and 440.

In 2023, we examined 123 sentences under Art. 20.29 of the CAO. In the vast majority of cases, offenders were punished for posting on social networks, mainly on VKontakte, but also on Odnoklassniki, Instagram, Telegram, and the local network of the Ural State University of Railway Transport. The offenders were punished for publishing the following types of materials:

Two people were punished for offline acts: the administrator of the Muzik box store in Ingushetia, who distributed Mutsuraev’s CDs (three protocols), and a prisoner of the Lipetsk colony who gave other prisoners a banned Islamic book to read[52]. In addition, the Alushta Muslim community was fined after two books that are on the Federal List of Extremist Materials were found in its Yukhara-Jami mosque, The Prophet Muhammad Mustafa-2 by Osman Nuri Topbash and The Values of Dhikr by Sheikh Muhammad Zakaria Kandehlavi[53].

According to our data, most of them paid fines ranging between 1000 and 3000 rubles. Seven people were sentenced to administrative arrests.

According to the Supreme Court, 54 decisions under Article 20.3.2 of the CAO came into force in 2022. In 2023, there were at least 35 decisions under this article.

We know of only two cases of punishment under Part 2 of this article (online calls to carry out actions aimed at violating the territorial integrity of the Russian Federation).

In Tyva, a resident of Kyzyl was fined 70000 rubles for publishing a post on VKontakte with calls for armed action against the current authorities in order to seize power and ensure the republic’s secession from the Russian Federation. In Karelia, a local resident was fined 35000 rubles for a post of unknown content on VKontakte.

We have mentioned in this report the 1136 sentences which we have no reason to consider unlawful. However, excluding the new articles of the CAO that we consider unlawful in general, we have to add that we are aware of 58 more cases of unlawful punishment under Article 20.3.1, 147 — under Article 20.3, 38 — under Article 20.29, and 3 — under Article 20.3.2, with a total of 246 decisions. Thus, the proportion of unlawful decisions on the same set of articles of the Code of Administrative Offences decreased compared to the previous year (282 unlawful vs. 966), from 22.6 % down to 17.8 %.

[1] N. Yudina. The New Generation of the Far-Right and Their Victims. Hate Crimes and Counteraction to Them in Russia in 2023 // SOVA Center. 2024. February 14 (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/reports-analyses/2024/02/d47069/).

[2] M. Kravchenko. Inappropriate Enforcement of Anti-Extremism Legislation in Russia in 2023 // SOVA Center. 2024. March 18 (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/publications/2024/03/d49483/; In Russian only for a while. further: M. Kravchenko. Inappropriate Enforcement…).

[3] Other cases of use of Art. 2073 cannot be classified as anti-extremism law enforcement, those are more akin to libel. Still, we believe that criminalization of both "fakes" about the army and libel is generally wrong.

[4] According to the Criminal Code, extremist crimes are crimes committed with a hate motive, as defined in Art. 63 of the CC. The list of offenses classified as “extremist” in the CC is currently established by directive of the Prosecutor General's Office and the Ministry of Internal Affairs. See: What constitutes an “extremist crime” // SOVA Center (https://www.sova-center.ru/directory/2010/06/d19018/).

[5] We do not include wrongful convictions for damage to material objects. On those, see: M. Kravchenko. Inappropriate Enforcement…

[6] Data as of March 11, 2024.

[7] Consolidated statistics on the state of criminal record in Russia for the first half of 2023 // Website of the Judicial Department at the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation. 2023. October 17 (http://www.cdep.ru/index.php?id=79&item=7900).

[8] Art. 2052 of the CC was first in terms of the number of convictions for statements — 167 people (318 for the entire year 2022). It is followed by Art. 280 of the CC with 149 people, (356 for the entire 2022). Art. 282 of the CC — 34 people (51 in 2022); Art. 3541 of the CC — 31 people (42 in 2022). Art. 2803 of the CC — 15 people, Part 2 of Art. 2073 of the CC — 10 people. Art. 2824 — 9 people. Part 1 of Art. 148 of the CC — 7 people (14 in 2022). For more information see: Official statistics of the Judicial Department of the Supreme Court on the fight against extremism for the first half of 2023 // SOVA Center. 2023. October 18 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2023/10/d48791/).

[9] Consolidated statistics on the activity of federal courts of general jurisdiction and magistrate courts for the first half of 2022 // SOVA Center. 2022. October 15 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2022/10/d47063/).

[10] Prior to 2018, convictions for statements were divided into “inappropriate” and “all other.”

[11] Text included in: The Rabat Plan of Action on the prohibition of advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility, or violence // UN. 2013. 13 January (https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Opinion/SeminarRabat/Rabat_draft_outcome.pdf).

[12] The court sentenced a member of a neo-Nazi community who recruited a minor and prepared a terrorist act // Official website of the 1st Eastern District Military Court. 2023. April 23 (http://1vovs.hbr.sudrf.ru/modules.php?name=press_dep&op=1&did=724).

[13] M. Kravchenko. Inappropriate enforcement…

[14] All of the numbers below are based on the sentences that we know about. But with the available volume of data, we can assume that the observed patterns and proportions will be approximately the same for the entire volume of sentences.

[15] On “Citizens of the USSR,” see: Akhmetyev Mikhail. Citizens without the USSR. Communities of “Soviet citizens” in modern Russia. Moscow: SOVA Center, 2022.

[16] For more see: O. Sibireva. Challenges to Freedom of Conscience in Russia in 2023 // SOVA Center. 2024. March 5 (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/religion/publications/2024/03/d47072/ ; further: O. Sibireva. Challenges to Freedom of Conscience…).

[17] N. Yudina. The New Generation of the Far-Right and Their Victims….

[18] Turik Alexander // SOVA Center Directory ( https://ref-book.sova-center.ru/index.php/%D0%A2%D1%83%D1%80%D0%B8%D0%BA_%D0%90%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BA%D1....

[19] Yegor Prosvirnin // SOVA Center Directory https://ref-book.sova-center.ru/index.php/%D0%9F%D1%80%D0%BE%D1%81%D0%B2%D0%B8%D1%80%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%....

[20] See: In St. Petersburg, a verdict was passed in the case of denial of the Holocaust and the heroic feat of Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya // SOVA Center. 2023. August 24 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2022/09/d46908/).

[21] For more see: O. Sibireva. Challenges to Freedom of Conscience…

[22] Art. 2824 of the CC criminalizes the repeated violation under Art. 20.3 of the CAO by a person penalized under this article (it should be borne in mind that according to Art. 4.6 of the CAO the violator is considered to have been penalized within one year from the date of entry into force of the ruling on imposing a penalty until the expiration of one year from the date of completion of execution of this ruling).

[23] Note that this report does not take into account clearly wrongful convictions.

[24] Remember that since the beginning of 2021, this article was partially decriminalized, a similar Art. 20.3.2 of the COA was introduced, and criminal liability under Art. 2801 only occurs one year after imposition of administrative sanctions.

[25] The group “Citizens of the USSR. Orel,” where the materials were allegedly published, had been blocked for two years by the time the criminal case was initiated. Florinsky claimed that he first saw the video during interrogation.

[26] It is not known which branch of the ROCA he belongs to.

[27] See for example: N. Yudina. Anti-Extremism in Virtual Russia in 2014-2015. // SOVA Center. 2016. August 24 (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/misuse/reports-analyses/2016/08/d35262/).

[28] N. Yudina. Anti-extremism in Quarantine: The State Against the Incitement of Hatred and the Political Participation of Nationalists in Russia in 2020 // SOVA Center. 2020. March 12 (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/reports-analyses/2021/03/d43830/).

[29] N. Yudina. In the Absence of the Familiar Article. The State Against the Incitement of Hatred and the Political Participation of Nationalists in Russia in 2019 // SOVA Center. 2020. March 17 (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/reports-analyses/2020/03/d42196/).

[30] Cases of terrorist propaganda in pre-trial detention centers and places of detention. 2023 // SOVA Center. 2023. June 6 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2023/06/d48204/

[31] See: M. Kravchenko. Inappropriate Enforcement…

[32] Consolidated statistics on the state of criminal record in Russia for the first half of 2023 // Judicial Department under the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation. 2023. October 17 (http://www.cdep.ru/index.php?id=79&item=7900).

[33] In terms of the number of convicted persons, Art. 2822 tops the list, as usual, with 150 people; Art. 2055 was used against 77 people; Art. 2821 against 23 people, and Art. 2054 against 21 people. Note also that in the first half of 2023, 13 people were convicted under Part 1 of Art. 2823 on the financing of extremist activities.

[34] For more see: Court decision on liquidation of right-wing radical organizations in Omsk // SOVA Center. 2004. April 30 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/docs/2004/04/d8899/).

[35] See: N. Yudina. The New Generation…

[36] A.U.E. movement recognized as extremist // SOVA Center. 2020. August 17 (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/persecution/2020/08/d42774/)

[37] Dmitry Gromov. AUE: kriminalizatsiya molodezhi i moralnaya panika. Moscow: Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 2022.

[38] See: M. Kravchenko. Inappropriate Enforcement…

[39] For more see: A group of "Citizens of the USSR" from Tatarstan recognized as extremist // SOVA Center. 2023. June 13 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2023/07/d48374/).

[40] See: M. Kravchenko. Inappropriate Enforcement…

[41] The Supreme Court has recognized the "International LGBT public movement" as an extremist organization // SOVA Center. 2023. November 31 (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/persecution/2023/11/d49011/).

[42] The National Socialist Society // SOVA Center Directory(https://ref-book.sova-center.ru/index.php/%D0%9D%D0%B0%D1%86%D0%B8%D0%BE%D0%BD%D0%B0%D0%BB-%D1%81%D0... ).

[43] In February 2023, the suspect charged with attempting to blow up a mosque was sentenced to 16 years under Art. 2053 of the CC (training in order to carry out terrorist activities).

[44] For more see: Another organization of "Citizens of the USSR" banned in Krasnoyarsk// SOVA Center. 2024. February 8 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2024/02/d49270/).

[45] Not counting the 395 local Jehovah's Witness organizations banned along with their Management Center and listed in the same paragraph with it.

[46] For more see: N. Yudina. Attack on Organizations…

[47]Vera Alperovich. The Nationalists Are Building up the Pace. Public Activity of Far-Right Groups, Winter-Spring 2023 // SOVA Center. 2023. June 10 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2023/07/d48353/).

[48] Russian Volunteer Corps // SOVA Center Directory (https://ref-book.sova-center.ru/index.php/%D0%A0%D1%83%D1%81%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%B9_%D0%B4%D0%BE%D0....

[49] There are also articles of the Administrative Code applicable to non-enforcement of decisions regarding restrictions on access to Internet resources, as well as some parts of Article 13.15 of the Administrative Code, related to the publication in the media of materials corresponding in content to several anti-extremist articles of the Criminal Code, but we have no information on the application of these norms.

[50] For more see: M. Kravchenko. Inappropriate Enforcement…

[51] Consolidated statistics on the state of criminal record in Russia for the first half of 2023 // Judicial Department of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation. 2023. October 17 (http://www.cdep.ru/index.php?id=79&item=7900).

[52] One of the following three books: Abu Abdallah Muhammad ibn Salih al-Uthaymeen. The Ideal Rules on the Beautiful Names and Attributes of Allah; Abdul-Ghani al-Jamma. Al-Iqtisadu fil-i'tikad = The Middle Ground in Belief; Abu Abdallah Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Zahabi. Al-Kabir. The Book About Great Sins and Explaining Forbidden Deeds.

[53] We consider the ban of one of the two books, The Values of Dhikr, to be unlawful: we did not find any aggressive statements in it, and it has a peaceful nature in general.