Summary

Systematic Racist and Neo-Nazi Violence : Attacks Against “Ethnic Outsiders” : Attacks against the LGBT : Attacks against Ideological Opponents : Other Attacks

Crimes against Property

Criminal Prosecution for Violence

Criminal Prosecution for Crimes against Property

Crime and punishment statistics

This report by SOVA Center[1] is focused on the phenomenon of hate crimes, i.e. on ordinary criminal offenses that were committed on the grounds of ethnic, religious or similar hostility or prejudice[2], and on the state’s counteraction to such crimes.

This is the third year that we have issued such report. Previously, sections on hate crimes were included in the single large annual report that encompassed both criminal and political activity of nationalists, as well as all measures to counteract them.

Summary

According to the monitoring data of SOVA Center, the number of racist and neo-Nazi-motivated attacks decreased in 2019, although the share of murders went up. The primary victim group is, as before, "ethnic outsiders", and the share of this group in the total number of victims has also increased.

Last year, there were two incidents of criminal nature that caused mass unrest under xenophobic slogans. The most notable of them were the anti-Roma acts in the Chemodanovka village of the Penza region. For the first time in many years, we learned about organized groups of ethnic minorities – the Yakut “Ooss Tumsuu” and the Azerbaijani VBON (“Vo Blago Obschego Naroda”, For the Good of the Common People).

The number of attacks on members of the LGBT community and on those deemed as such also increased in the past year, while the number of attacks on “ideological opponents”, including those who were viewed as “national-traitors”, significantly declined. The pro-Kremlin group SERB remains active, but its activity is tempered; in 2019, its members refrained from physical attacks almost entirely, limiting themselves to verbal assault.

Instances of damage to buildings, monuments, cemeteries, and various cultural sites, motivated by religious, ethnic, or ideological hatred are less frequent than before. However, as is the case with violence, the proportion of dangerous acts – explosions and arson – has increased in the past year. The number of desecrations of religious sites remained approximately the same. First and foremost, the number of attacks on ideological sites and objects has decreased.

As for the practice of law enforcement for hate crimes, the number of convictions in 2019 was down, which correlates with the decreasing rate of assaults. The quality of the efforts to combat hate crimes is debatable: on the one hand, members of well-known neo-Nazi groups such as Stolz Khabarovsk went behind bars last year. On the other hand, the proportion of suspended sentences for hate crimes started to grow again.

We are seeing a decrease in the criminal activity of the ultra-right, but we are also seeing a growing share of more dangerous violence. In addition, there is reason to believe that hate crimes have become even more latent. We cannot say that ideologically motivated violence is going away, so law enforcement agencies have plenty of work to do in this direction.

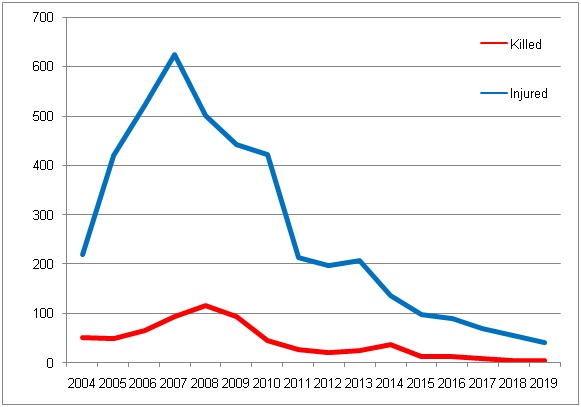

Systematic Racist and Neo-Nazi Violence

In 2019, at least 45 people became victims of racist and other ideologically motivated violence; at least five of them were killed and the others were injured or beaten; two people received death threats. Unfortunately, these numbers do not cover the whole country and do not include victims in the republics of the North Caucasus and Crimea, where our methods are, regrettably, not applicable. The number of people killed increased in 2019 compared to the previous year, although the total number of hate-motivated attacks is decreasing: in 2018, four people died and 55 were injured or beaten[3]. Of course, our data is quite incomplete, especially for the last year, as we often do not find out about crimes until much later[4]. Unfortunately, we cannot compare our numbers with official or any other data because no statistics on hate crimes exist in Russia.

Information about such crimes is becoming more fragmented with every passing year. For a while now, the way the media has been describing crimes has been making it impossible to determine whether they were motivated by hatred. More often than not, the media simply does not report such incidents. The victims rarely, if ever, turn to social organizations, let alone the police, rightly apprehensive of getting in trouble with the law enforcement agencies. The attackers, who merely a few years ago used to fearlessly publish videos of their “acts”, have become more cautious. But even if such videos do appear, it is often not possible to verify their authenticity and establish the time and place of the attack. For example, on 31 December 2019, an ultra-right Telegram channel wished everyone a Happy New Year by publishing a video showing a series of arson attacks and beatings of people in the streets and in train cars, two of the attacks involving use of knives. The video ended with a young man wearing a mask writing “Happy New Year NS/WP” on the wall and raising his hand in a Nazi salute. From this video, it is absolutely impossible to establish where and when these acts were committed.

As a result, in no way does our data reflect the true scope of what is happening. But since our methodology has not changed since the start of the data collection, we are able to see the dynamics and can state that, compared to the events of a decade ago, the progress is undeniable.

Chart 1. Trends in Hate-Motivated Attacks and Killings (2004–2019)[5]

In the past year, we have recorded attacks in 18 regions of the country (in 2018 – in 12 regions). Moscow (two killed[6], 11 injured and beaten) and St.-Petersburg (nine injured and beaten) traditionally lead in terms of violence level. A significant number of victims (three) was reported in the Sverdlovsk region.

In the past year, we have not recorded any hate crimes in the Kaluga, Kirovsk, Novosibirsk, Samara, and Tyumen regions. At the same time, assaults were reported in the regions where they have not been reported in the past year, namely, the Vologda, Voronezh, Leningrad, Nizhny Novgorod, Rostov, and Tula regions, Altai Krai, Primorsky Krai, Khabarovsk Krai, Sakha Republic (Yakutia), and Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug.

According to our data, in the past ten years, in addition to Moscow, St. Petersburg, and the Moscow region, crimes have been recorded practically annually in the Volgograd, Voronezh, Kaluga, Kirov, Kursk, Leningrad, Nizhny Novgorod, Novosibirsk, Omsk, Rostov, Samara, Sverdlovsk, and Tula regions, Primorsky Krai, Krasnodar Krai, and Khabarovsk Krai. However, it is also possible that the media and the Prosecutor’s offices of these federal subjects are just better at covering the situation.

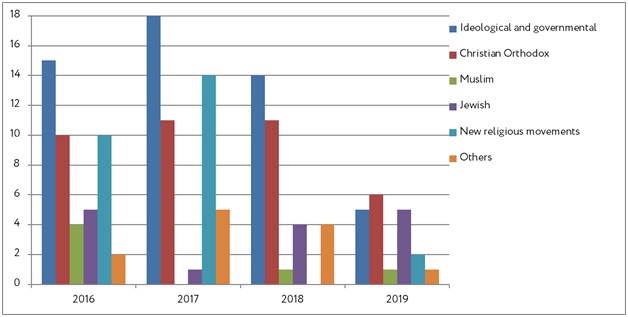

Chart 2. Types of Victims of Ideologically Motivated Violence (2016 - 2019)

Attacks Against “Ethnic Outsiders”

Those whom attackers perceived as “ethnic outsiders” remain the largest group of victims, and their numbers have increased compared to the previous year. In 2019, we recorded 21 ethnically motivated attacks. In 2018, we reported 20 victims.

Victims in this category include natives of Central Asia (three killed, 11 beaten compared to two killed, three beaten in 2018) and Caucasus (one beaten, none reported in 2018) and individuals of unidentified “non-Slavic appearance” (three beaten compared to 12 in 2018); the latter were described by the eyewitnesses as “Asian” so, most likely, they too were natives of Central Asia.

Unfortunately, threats and violence by the police, including those made under xenophobic pretext, are not uncommon. Law enforcement officers harbor the same prejudices and biases as common citizens and often abuse their positions. But information about the details is almost always classified, making the analysis of the dynamics of motivated violence by the police force impossible. Only the most egregious cases become public knowledge, such as the December 2019 police raid in Khabarovsk, when more than a hundred migrants were beaten by the cops shouting xenophobic slurs such as “Narrow-eyed, we are sick of you! Get out of here and don’t let us see you here again!”[7].

We are aware of only one attack on a black man[8] that occurred throughout the past year (one person was killed in each of the years 2017 and 2018). However, it is likely that many more such attacks are happening, as the level of intolerance towards black people in Russia is quite high. This is clearly demonstrated by what happened in Stavropol, where some of the local owners simply refused to allow black patrons in their establishments. Egidio Nanga, a student from Angola, reported the situation and said that he and his friends had been repeatedly turned away from several restaurants and clubs, such as the Goldy club, the Forbs restaurant, and the Yes cafe[9].

Attacks on Jews in Russia do not occur every year, although anti-Semitic rhetoric is still very visible in the right-wing segment of the Internet. Perhaps the reason for the low frequency of attacks is that it is difficult to visually distinguish Jews from others. Still, last year, one case of an anti-Semitic attack was reported in St. Petersburg[10].

The 2019 poll by the Levada Center[11] showed that the Roma were the most unpopular ethnic group in Russia: the number of individuals wishing to expel them from the country exceeded 1.5 times the number of those supporting the expelling of Africans and natives of Central Asia.

The largest ethnically charged mass riots of 2019 were directed against the Roma. One person has been killed in a mass brawl that erupted on 13 June in the Chemodanovka village in the Penza region. The reasons for the fight are still unknown. According to some Penza media, it all started after the Roma had harassed a daughter or daughters of local residents; then several of them came to the Roma house to "set up a meeting". Nadezhda Demeter, the head of the Federal National and Cultural Autonomy of Russian Roma, claimed that the incident had occurred because of a children’s quarrel, after which the villagers had come to the Roma house. In a mass brawl that occurred the next day at the pond, five people were injured. One of them, Vladimir Grushin, born in 1985, later died. There were no police in the village, and the clash was only stopped by riot police called in from the regional center. 174 people were taken to the internal affairs agencies for questioning and three Roma who had participated in the conflict were arrested. The following day, the local residents held a “people’s rally” and blocked a federal road, demanding the eviction of the Roma. On 15 June, a Roma house in a neighboring village of Lopatki went up in flames. After that, a message spread, citing the head of the village council, that all the local Roma had been forcibly removed by the authorities; this was promptly refuted by a spokesperson for the Penza region governor, but the Roma have really virtually disappeared from both villages[12].

The events in the Penza region have elicited a massive response on social networks: there was talk of the start of “war” against the Roma and fake news reports alleging that the Roma had appointed July 1 as the day of revenge and were marching toward Chemodanovka with gasoline. Roskomnadzor even demanded that social networks delete the information about the conflict in the village, which the Prosecutor General’s Office had deemed false. For instance, VKontakte has blocked the “Chemodanovka on Fire” community “due to calls for violence”.

It was not only in connection with what had happened in Chemodanovka that threats against the Roma were spread on social networks. A Cossack community page and far-right pages in the VKontakte social network posted a photo of a Roma man with a link to his VKontakte page and a call to all Cossacks “to give him the full treatment”.

Another major example of mass riots against migrants resulting from domestic violence is the protests in Yakutsk in March 2019, where the rape of an ethnic Yakut woman by migrants from Kyrgyzstan provoked a series of threats to migrants and the destruction of their vegetable stands[13].

Very little is known about organized racist groups of ethnic minorities (like the Kyrgyz “Patriot” gang that would beat up Kyrgyz girls for allegedly going out with “non-Kyrgyz” young men[14]).

One such group surfaced in connection with the Yakutsk riots. “Us Tumsuu”, a local vigilante nationalist movement[15] that cooperates with the local authorities and advocates for conservative values, was suspected of being involved. For instance, in the first days of 2019, the members of the movement together with police raided Yakutsk nightclubs with the aim of intimidating the migrants and admonishing the Yakut girls, who, according to the activists, should “return to their own — the Yakut”[16].

In 2019, yet another ethno-nationalist organization VBON, “Vo Blago Obschego Naroda” (For the Good of the Common People), came to light. This Azerbaijani movement that promotes traditional values and a healthy lifestyle became “famous” after videos of beatings and screenshots bearing threats to “those who insult the Azerbaijani people”, signed with the acronym VBON, spread via social networks and a Telegram channel. Assaults and threats committed in Russia[17] were motivated by the hatred toward both the Armenians and “the insulters” of the Azerbaijanis[18].

In addition to the above-mentioned, 2019 witnessed assaults on other “ethnic outsiders” under xenophobic slogans. For example, a student from India was beaten in Barnaul and a resident of Kalmykia – in Volgograd.

Attacks against the LGBT

The number of attacks against the LGBT community was higher than in the preceding year – one killed[19], seven injured and beaten (vs. one killed and five injured and beaten in 2018). There are no official statistics in Russia on victims of violence against the LGBT. As before, we have to emphasize that our data is minimal and the true level of homophobic violence is unknown. In 2019, the victims were comprised primarily of pickets or participants of other events associated with the LGBT; but there were also street attacks on individuals who were mistaken for the LGBT due to their appearance, as happened in Yekaterinburg when a group of aggressive young men attacked a man they suspected of being gay[20] and in St.-Petersburg when the girls mistaken for lesbians were beaten[21].

The murder of activist Elena Grigorieva in St. Petersburg on the night of July 19 was widely reported in the media. Grigorieva, who was openly bisexual, was an LGBT rights activist prominent in the St.-Petersburg LGBT movement. Her name was on the hit list published on the website of the homophobic group “Pila” (“Saw”)[22]. Grigorieva was also receiving threats from the well-known St.-Petersburg homophobic activist Timur Bulatov and some nationalists. She contacted the police more than once because of the threats but “there was no reaction whatsoever [on behalf of the law enforcement agencies]”. Yet, at the time of the report’s writing, the main version of the murder is drunken homicide. Police have detained a suspect, with whom, according to investigators, the activist had had a personal conflict that had led to her death[23].

In addition to physical assault, the LGBT activists regularly face threats from anti-gay individuals and right-wing radicals of all sorts. For example, threats from Bulatov have continued even after Grigorieva’s murder, with Karolina Kanaeva, an activist from Saransk, being one of the recipients[24]. On July 1, the above-mentioned “Pila” group published a hit list of the activists that it was threatening. On July 17, the LGBT Resource Center in Yekaterinburg received a letter signed by “Pila” demanding the Center’s shutdown by the end of July and the transfer of its funds to the charity “Podari Zhizn” [Gift of Life][25].

National Conservative Movement (NKD), led by Valentina Bobrova and Mikhail Ochkin, was very actively engaged in anti-gay acts throughout the past year. Together with Archpriest Vsevolod Chaplin, NKD opposed “the LGBT lobby and anti-Christian trends’ offensive against Russia” by holding various anti-gay actions and pickets. And on August 28 in Moscow, a play at Teatr.doc about the situation of homosexuals in Russia was disrupted by NKD, the pro-Kremlin SERB group, and the National Liberation Movement (NOD) activists[26].

Attacks against Ideological Opponents

In 2019, the number of attacks by the ultra-right against their political, ideological, or “stylistic” opponents – four beaten – decreased significantly compared to the 19 beaten in previous year of 2018[27]. Both a politicized representative of youth subculture (anti-fascist) and an apolitical rapper are among the victims.

This group also includes the individuals perceived to be “a fifth column” and “traitors to the Motherland”, mainly the protesters assaulted by the SERB (South East Radical Bloсk) group, led by Igor Beketov (aka Gosha Tarasevich)[28].

Generally, the last year’s acts of the pro-Kremlin SERB group were very visible. Fortunately, there were virtually no serious assaults; the activists have limited themselves to provocations, verbal insults, and shouts at the protesters. In particular, in February, they disrupted the screening of the film “Prazdnik”, or “Holiday”, at the Memorial Society; in April, they interfered with the members of the action group “Against Torture and Discrimination”, led by Lev Ponomarev, that were holding a series of solitary pickets in front of the FSB building and in Manezhnaya Square in support of those detained in the Network (“Set’”) case; finally, in December, they tried to prevent an opposition rally in Pushkinskaya Square.

The theme of threats by the ultra-right remained relevant throughout the year. Photos and personal data of anti-fascists, left-wing activists, independent journalists, and law enforcement officers, accompanied by threats, were published on the social media pages of the far-right organizations and groups. Photos of “traitors”, that is, the far-right individuals who testified against former “associates” in trials, also appeared in social networks.

Other Attacks

In 2019, we have recorded seven attacks on the homeless (one killed, six injured), which is twice as low as in the previous year (one killed, 13 injured in 2018). However, we believe that the number of such attacks was much higher since the homeless are perhaps the least protected from aggression and violence. Our statistics only include the incidents where investigation had already established hate as a motive, as happened in Nizhny Novgorod, where four young men were detained for killing a homeless man out of “the motive of hate for the socially disadvantaged segments of the population”.

We are not aware of any religious hate attacks committed in 2019.

Jehovah's Witnesses, who previously made up the vast majority of the victims of these attacks, do not report attacks anymore. It is possible that, after their properties had been seized and their missionary activities banned, they have become less visible and the frequency of attacks on them has indeed decreased. However, the repressive campaign against this religious group cannot leave no trace: for instance, at the end of December 2019, the car belonging to the resident of the Sukhobuzimskoye village of Krasnoyarsk Krai Kirill Mikhailin had its windshield smashed and a handwritten note with profanities against Jehovah’s Witnesses was thrown inside the car. Mikhailin states that his family has been receiving threats because of their religion throughout the whole past year[29].

Our statistics customarily include those who tried to intervene and protect the victims. For example, during the above-mentioned homophobic attack in Yekaterinburg, two passersby were injured when they went to the aid of the man who was being attacked.

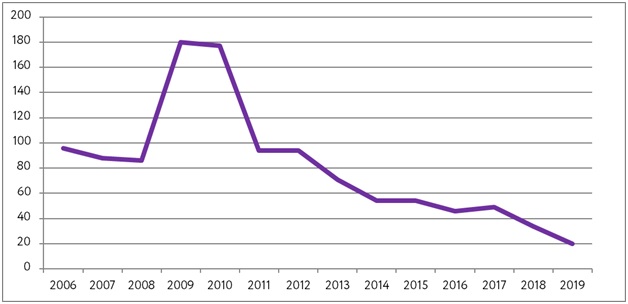

Crimes against Property

Crimes against property include damage to cemeteries, monuments, various cultural sites, and property in general. They are categorized under several different articles of the Criminal Code, but the enforcement is not always consistent. Such acts are usually referred to as vandalism, and we used to apply this term, too, before rejecting it two years ago, as the term “vandalism”, be it in the Criminal Code or everyday language, clearly does not encompass all possible types of damage to property.

Chart 3. Trends in Crime against Property (2006–2019)

Compared to 2018, 2019 witnessed a significant decrease in the number of religious, ethnic, or ideological hate crimes against property: at least 20 in 17 regions in 2019 vs. at least 34 in 23 regions in 2018. Our statistics does not include isolated cases of neo-Nazi graffiti and drawings on buildings and fences but it does include serial graffiti (law enforcement considers graffiti to be either a form of vandalism or a means of public statement).

The number of ideological sites and objects damaged in 2019 was also lower – 5 vs. 14 in 2018. In the past year, monuments to victims of World War II, Sino-Soviet Friendship Monument, and Memorial to Rapper XXXTentacion have been damaged.

Chart 4. Desecrated Religious and Ideological Sites (2016–2019)

As before, most of these acts target religious sites and objects. Russian Orthodox churches and crosses were the most frequent target of desecration (six incidents in 2019 vs. 11 in 2018). Jewish sites come in second with five instances (four in 2018). New religious movements experienced two incidents of building damage (none reported in 2018). Muslim and Catholic sites and objects had one incident each; in 2018, one act of desecration against a Muslim site was reported, and none against Catholic sites.

On the overall, the rates of attacks against religious sites have gone down from 30 in 2017 and 20 in 2018 to 15 in 2019. On the other hand, the share of the most dangerous acts – arson and explosions – has increased to 30%, or 6 out of 20 (in 2018, it was 7 out of 35). The highest-profile attack came on May 16 when the People's Resistance Association (ANS) assaulted the patriarchal residence in Chistiy pereulok in Moscow. ANS members placed a banner that said “Apologize for EKB” (EKB stands for “Yekaterinburg”) on the gates and threw smoke bombs onto the grounds, which also house the office of the Moscow Patriarchate. The attack was in support of protests against the construction of a new church on the site of a park in Yekaterinburg[30].

The regional distribution has changed noticeably throughout the year. In 2019, this type of crime was reported in the following 11 regions where it has not occurred before: the Astrakhan, Vladimir, Volgograd, Irkutsk, Moscow, and Tver regions, Altai Krai, Krasnoyarsk Krai, Primorsky Krai, the Kabardino-Balkar Republic, and Sevastopol; on the contrary, the following 17 regions where such crimes have been reported before went off the list in 2019: the Arkhangelsk, Voronezh, Kemerovo, Leningrad, Murmansk, Ryazan, Samara, Sverdlovsk, Smolensk, Tula, Ulyanovsk, Chelyabinsk, and Yaroslavl regions, the Republic of Karelia, the Republic of Khakassia, Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug, and Crimea.

For the first time in our practice, the geographical spread of the acts of violence (18 regions) turned out to be wider than that of xenophobic vandalism (17 regions). Both types of crimes were reported in five regions (same as in 2018): in Moscow, St.-Petersburg, Altai Krai, and the Vologda and Moscow regions.

Criminal Prosecution for Violence

The number of the convicted of violent hate crimes was lower in 2019 than in the previous year. In the past year, in St.-Petersburg, Omsk, and the Khabarovsk region, at least four guilty verdicts in which the hate motive was officially recognized[31] were issued. 10 defendants were found guilty in these trials[32] compared to 11 (in 11 regions) in 2018.

Worthy of note is the Zheleznodorozhny District Court of Barnaul guilty verdict for a xenophobic attack and insult targeting “the natives of the Caucasus” that occurred in one of the city’s shopping malls. During the investigation, the attacker justified his actions by saying that he was “outraged by the behaviour of foreign nationals who came [to Russia] from other countries”. Despite that fact, the criminal case was initiated without recognizing the hate motive, under Article 116.1 of the Criminal Code (“Battery committed by a subject of administrative penalty”), and later terminated due to the reconciliation of the parties.

Chart 5. Trends in Violent Hate Crimes: the Convicted and the Victims (2004–2019)

In other guilty verdicts, racist violence was categorized under the following articles containing hate motive as a categorizing attribute: “Infliction of light bodily harm”, “Battery”, and “Involvement of a minor in a criminal group”. The first two articles are applied virtually every year. Three convictions for violent crimes (compared to five in 2018) were based on Article 282 of the Criminal Code (“Incitement of hatred”), namely, Paragraphs A and C of Article 282 Part 2 of the Criminal Code (“Incitement of hatred committed with the use of violence or with the threat of its use” or “committed by an organised group”). Article 280 of the Criminal Code (“Public appeals for the performance of extremist activity”) was similarly invoked in three guilty verdicts. In two of them, it was used in conjunction with Article 282 of the Criminal Code and was added to other charges against the co-defendants in joint trials and the members of ultra-right groups, such as the Omsk group[33] and the founder and member of the group known as Stolz Khabarovsk[34].

Penalties for violent acts were distributed as follows:

- 1 person sentenced to more than 20 years in prison;

- 2 persons sentenced to 10 to 20 years in prison;

- 2 persons sentenced to 5 to 10 years;

- 3 persons received suspended sentences;

- 1 person sentenced to compulsory community service;

- 1 person relieved from punishment due to the expiration of the statute of limitations.

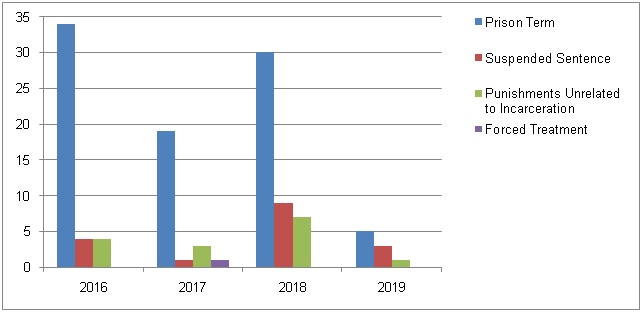

Chart 6. Criminal Penalties for Ideologically Motivated Violence (2016-2019)

We are aware of just one case of additional punishment, given to the above-mentioned Stolz group leader[35] who was barred from leading and participating in public organizations for eight years and from publishing appeals and any materials in public information and telecommunications networks, including the Internet, for two years.

As is evident from the above data, half of those convicted for violence (5 out of 10) have received prison time of various lengths. However, the share of suspended sentences is on the rise for the second consecutive year, having reached 30% in 2019 (3 out of 10), as compared to 20% (9 out of 45) in 2018.

We question the appropriateness of the suspended sentence given to the resident of Omsk for two attacks, a beating of a passerby suspected of being a drug user and a beating of a person of “non-Slavic appearance”[36]. The sentences received by two adolescents from St.-Petersburg for the perpetration of the “white subway car” attack – moderate suspended sentences – also seem to us far too mild[37], even though the convicted were minors when they committed the crime. We can't stress enough how extremely wary we are of suspended sentences for ideologically motivated attacks. According to our observations, such sentences very rarely prevent the assailants from committing similar crimes in the future.

Criminal Prosecution for Crimes against Property

We are not aware of any sentences for crimes against property where hate motive was cited in 2019. (In 2018, two such sentences were issued in two regions against six individuals, and in 2017 – three sentences in three regions against five individuals.)

We are aware of one instance when an ideologically motivated crime against property has not been categorized as a hate crime. Six members of the PNZS group (official documents list the full name of the group as “Perm Nazi Squad”) received two sentences for several graffiti and for setting fire to the United Russia offices in Perm. These acts were categorized under Part 2 Article 167 of the Criminal Code (“Wilful Destruction or Damage of Property by Means of Fire”), Article 2821 (“Organising of and Participation in an Extremist Community”), and Part 1 Article 282 of the Criminal Code (“Incitement of Hatred”); one of the convicts was sentenced under Part 2 Article 282 and Article 280 of the Criminal Code[38]. However, Part 1 of Article 282 has been decriminalized[39].

[1] Our work on this issue is supported by the Norwegian Helsinki Committee, International Partnership for Human Rights, and the European Commission.

On 30 December 2016, the Ministry of Justice has forcibly listed SOVA Center as “a non-profit organization performing the functions of a foreign agent.” We disagree with this decision and have filed an appeal against it.

[2] Hate Crime Law: A Practical Guide. Warsaw: OSCE/ODIHR, 2009 (available on the OSCE website in multiple languages, including Russian: http://www.osce.org/odihr/36426).

Alexander Verkhovsky. Criminal Law on Hate Crime, Incitement to Hatred and Hate Speech in OSCE Participating States (2nd edition, revised and updated). Мoscow, 2015 (available on the SOVA Center website: http://www.sova-center.ru/files/books/cl15-text.pdf).

[3] Data for 2018 and 2019 is provided as of 22 January 2020.

[4] In a similar report for 2019, we mentioned four dead and 53 injured and beaten. See: Natalia Yudina. The Far-Right and Arithmetic: Hate Crime in Russia and Efforts to Counteract It in 2018. // SOVA Center. 2019. 22 January (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2019/01/d40542/).

[5] Here and below all the data in the charts is based on the monitoring by SOVA Center.

[6] A year earlier, two people were killed.

[7] In Khabarovsk, police beat migrants while shouting xenophobic insults // SOVA Center. 2019. 23 December (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2019/12/d41885/).

[8] An African man beaten in Kudrov // SOVA Center. 2019. 16 January (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2019/01/d40524/).

[9] Stavropol Obschepit [public catering] against African students // Kavkaz.Realii. 2019. 11 December.

[10] St.-Petersburg: musician beaten and insulted by taxi driver // SOVA Center. 2019. 20 May (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2019/05/d41032/).

[11] Monitoring of xenophobic sentiments // Levada-Center. 2019. 18 September (https://www.levada.ru/2019/09/18/monitoring-ksenofobskih-nastroenij-2/).

[12] Anti-Roma riots in Chemodanovka // SOVA Center. 2019. 17 June (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2019/06/d41149/).

[13] Anti-migrant protests in Yakutsk. Restrictions introduced on the employment of foreigners // SOVA Center. 2019. 19 March (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2019/03/d40783/).

[14] Vera Alperovich, Natalia Yudina. The Ultra-Right in the Streets: Pro-Democracy Poster in Their Hands or a Knife in Their Pocket. Xenophobia and Radical Nationalism in Russia, and Efforts to Counteract Them in 2012 // 2013. 15 March (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2013/03/d26655/).

[15] Officially registered as the Center for Civic-Patriotic Education of Youth in Sakha Republic “Tri”.

[16] Taisiya Bekbulatova. The People is Sleeping Like a Bear – Do Not Wake It // Takie Dela. 2019. 5 April (https://takiedela.ru/2019/04/narod-spit-kak-medved/).

[17] At least one attack by the members of VBON on four gay men in Baku on August 6 has also been reported.

[18] Attacks and threats by the VBON movement // SOVA Center. 2019. 25 October (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2019/10/d41622/).

[19] The brutal murder of transgender woman Nika Surgutskaya. For additional information see: Kursk: brutal murder of transgender woman // SOVA Center. 2019. 24 April (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2019/04/d40936/).

[20] A homophobic attack in Yekaterinburg // SOVA Center. 2019. 16 September (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2019/09/d41469/).

[21] Several young men attack a group of girls, mistaking them for lesbians // SOVA Center. 2019. 10 December (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2019/12/d41822/).

[22] Ksenia Morozova. Pila Against LGBT: What Is Known About the Homophobic Movement That Is Believed to Have Been Involved in the Death of Elena Grigorieva // Sobaka. 2019. 24 July (http://www.sobaka.ru/city/society/94002).

[23] Activist Elena Grigorieva is murdered. Suspect arrested // SOVA Center. 2019. 23 July (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2019/07/d41276/).

[24] After the murder of Elena Grigorieva, her friend receives threats // OVD-info. 2019. 27 July (https://ovdinfo.org/express-news/2019/07/25/posle-ubiystva-eleny-grigorevoy-ee-znakomoy-postupayut-ugrozy).

[25] Yekaterinburg LGBT Resource Center About Threats of Violence by “Pila” // The Village. 2019. 17 July (https://www.the-village.ru/village/city/news-city/356591-lgbt-ugroza).

[26] NKD (National-Conservative Movement), SERB, and NOD (National Liberation Movement) disrupt Teatr.doc play // SOVA Center. 2019. 29 August (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2019/08/d41410/).

[27] Attacks of this type peaked in 2007 (7 killed, 118 injured); the numbers have since been steadily declining. After 2013, trends have been unstable.

[28] For more details see: Vera Alperovich, Natalia Yudina. The Pro-Kremlin and the Opposition: With the Shield or on It // SOVA Center. 2015. 27 July (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2015/07/d32502/).

[29] In Krasnoyarsk Krai, vandals smashed the windshield of the car belonging to a Jehovah’s Witness and threw in a note with profanities // SOVA Center. 2020. 9 January (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2020/01/d41917/).

[30] ANS activists hang banner and throw smoke bombs onto the ground of the patriarchal residence // SOVA Center. 2019. 17 May (https://www.sova-center.ru/religion/news/community-media/communities-conflicts/2019/05/d41022/).

[31] Only the verdicts in which the hate motive was officially recognized and which we consider appropriate are included in this count.

[32] One relieved from punishment due to the expiration of the statute of limitations.

[33] Omsk: guilty verdict for the local ultra-right group members remains unchanged // SOVA Center. 2019. 4 October (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/10/d40102/).

[34] The group was designated extremist in December 2017.

[35] In the Far East, the leader and a member of the “Stolz” group are convicted // SOVA Center. 2019. 26 June (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2019/06/d41188/).

[36] Omsk. Sentence delivered in the case of xenophobic attacks // SOVA Center. 2019. 7 October (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2019/10/d41549/).

[37] St.-Petersburg. “White subway car” attack perpetrators receive suspended sentences // SOVA Center. 2019. 3 September (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/09/d39950/).

[38] Court issues sentence for two members of “Perm Nazi Squad” // Центр «Сова». 2019. 29 July (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2019/07/d41299/); Perm: sentence in the “Perm Nazi Squad” case // SOVA Center. 2019. 14 August (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2019/07/d41220/).

[39] Putin signs laws partially decriminalizing Article 282 of the Criminal Code // SOVA Center. 2018. 28 December (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/lawmaking/2018/12/d40472/).