Summary

Criminal Prosecution :For Public Statements : For Participation in Extremist and Terrorist Groups and Banned Organizations

Federal List of Extremist Materials

The Banning of Organizations as Extremist

Sanctions for Administrative Offences

Crime and punishment statistics

This report[1] focuses on countering the incitement of hatred and political activity of radical groups, primarily nationalists, through the use of anti-extremism legislation. This counter-activity includes a number of articles of the Criminal Code (CC), several articles of the Code of Administrative Offenses (CAO), mechanisms for banning organizations and "information materials," blocking of Internet sites and resources, etc.

Countering hate crimes is not the subject of this report: that activity is covered in a separate, previously published report.[2] Yet another report, published in parallel, examines the cases of law enforcement that we consider unlawful and inappropriate; it also examines the legislative innovations of the past year in the field of anti-extremism.[3]

Summary

In 2021, we have witnessed an increase in the scale of criminal prosecution for "extremist statements." This increase was mainly contributed to by the numbers of those convicted under articles on public appeals to extremism and terrorism. The number of people convicted under other articles on public statements has also increased, but especially those convicted under the article on "insulting believers' religious feelings."

The focus of attention of law enforcement officers has undergone a significant shift: far more sentences were handed down last year for aggressive statements against the authorities (including against police and security forces), and the share of these sentences has even exceeded the share of sentences for ethnic xenophobia. And this trend is alarming: it is unlikely that public officials, especially those who carry arms, are in such need of protection under anti-extremism legislation. Increasing penalties for statements are also an issue of concern.

The number of those punished under administrative articles has also increased, mainly due to the article on the demonstration of prohibited symbols. It should be noted that, unlike those prosecuted under a similar article of the Criminal Code, the vast majority of those prosecuted for inciting hatred under the Administrative Code articles were punished for ethnic xenophobia.

In 2021, the growth of the Federal List of Extremist Materials slowed down again; although, throughout the years of its existence, law enforcement officers have not familiarized themselves with the basic bibliography rules and guidelines.

The pace of updating the Federal List of Extremist Organizations has increased, but we believe that almost half of the organizations added to it in 2021 were banned unlawfully. The list of organizations designated as terrorist has also been replenished. And while earlier it was primarily Muslim organizations that were being added to it, in 2021 there was only one such instance.

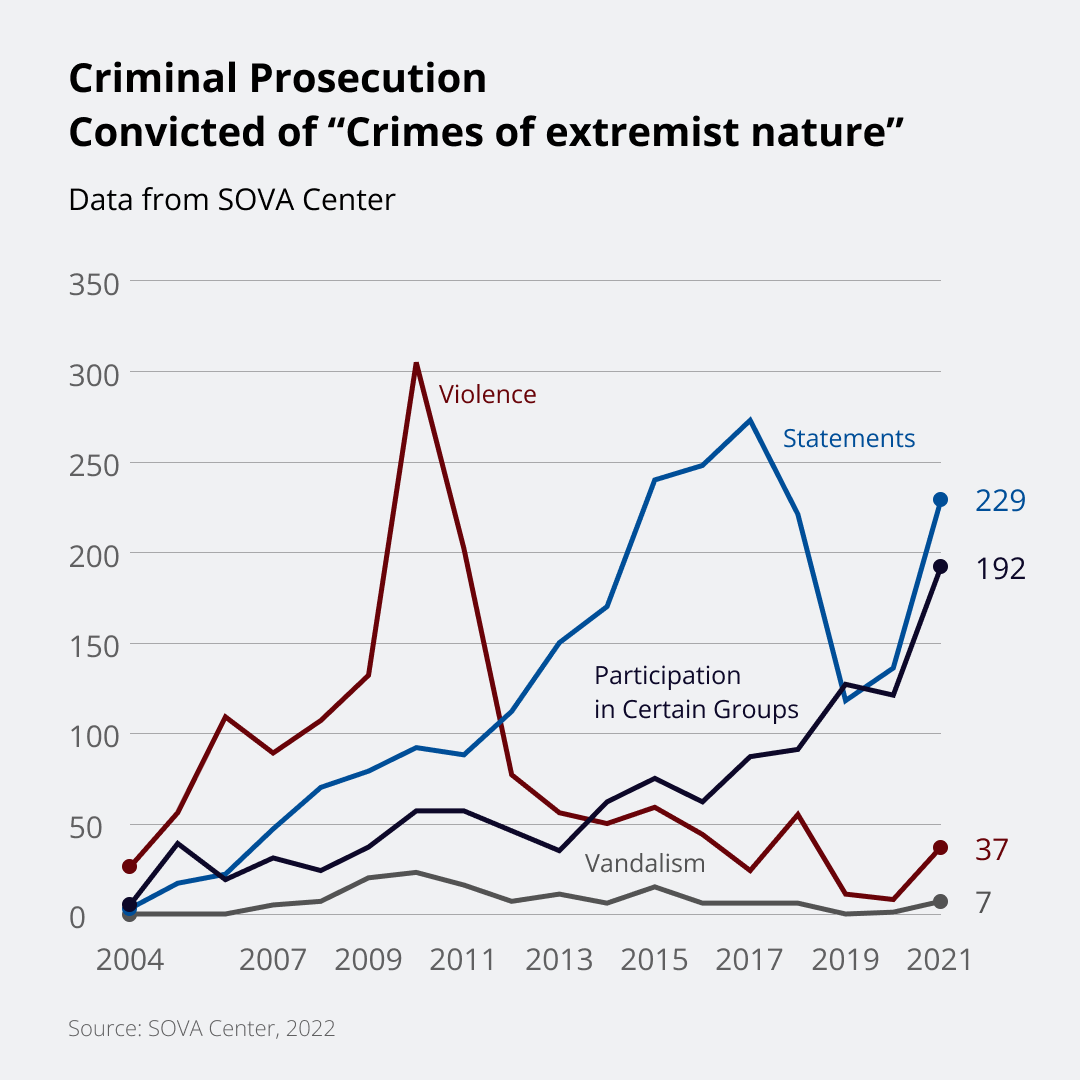

In our recent report on hate crimes, we also noted a sharp increase in the number of people convicted of such offenses: under articles on violence, and especially under articles on hate-motivated vandalism. At the same time, the increase in xenophobic violence in 2021 was not significant, and 2020 even saw a decrease. The level of crimes against property fluctuated slightly.

No official statistics on counteraction to extremism in 2021 are available yet, but the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Lebedev recently reported that 606 people were convicted of "extremist crimes" last year, compared to 325 a year earlier.[4] There has not been such a sharp increase since at least the early 2010s. This category includes hate crimes against people or property, participation in extremist communities, and most of what we call "extremist statements."

Comparing the overall increase in the number of sentences, quoted by Lebedev, with the data from our two reports, it is possible to claim that in 2021, law enforcement in all types of "extremist crimes" has sharply intensified.

Meanwhile, we see no reason for this. The radicalization of certain movements that pose danger to society (like the radical far-right, for example) or to the political regime could be one reason, but such radicalization is not being observed. At the same time, the intensification of law enforcement activities is observed across the entire political spectrum – in relation to nationalists, various religious movements, the left, and liberals. Major political events of the year, for example, Alexei Navalny's return to Russia or the September elections might also serve as a reason, but no such connection could be traced in most of the cases.

Thus, the authorities, for no apparent political reason, have practically doubled their repressive efforts in terms of protecting the security of society and, first of all, themselves.

Criminal Prosecution

For Public Statements

By persecution for public "extremist statements" we mean statements that were qualified by law enforcement agencies and courts under articles 282 (incitement to hatred), 280 (calls for extremist activity), 2801 (calls for separatism), 2052 (calls for terrorist activity and justification thereof), 3541 (rehabilitation of Nazi crimes, desecration of symbols of military glory, insulting veterans, etc.) and Parts 1 and 2 of Article 148 (the so-called insults of religious believers' feelings) of the Criminal Code. The last three articles do not formally refer to "extremist crimes": Article 2052 is an anti-terrorist one, but since it has little to do with terrorism itself, we view it rather in the broader concept of extremism; the other two are so closely related to extremism that it is a pure accident that they do not qualify as anti-extremist.[5]

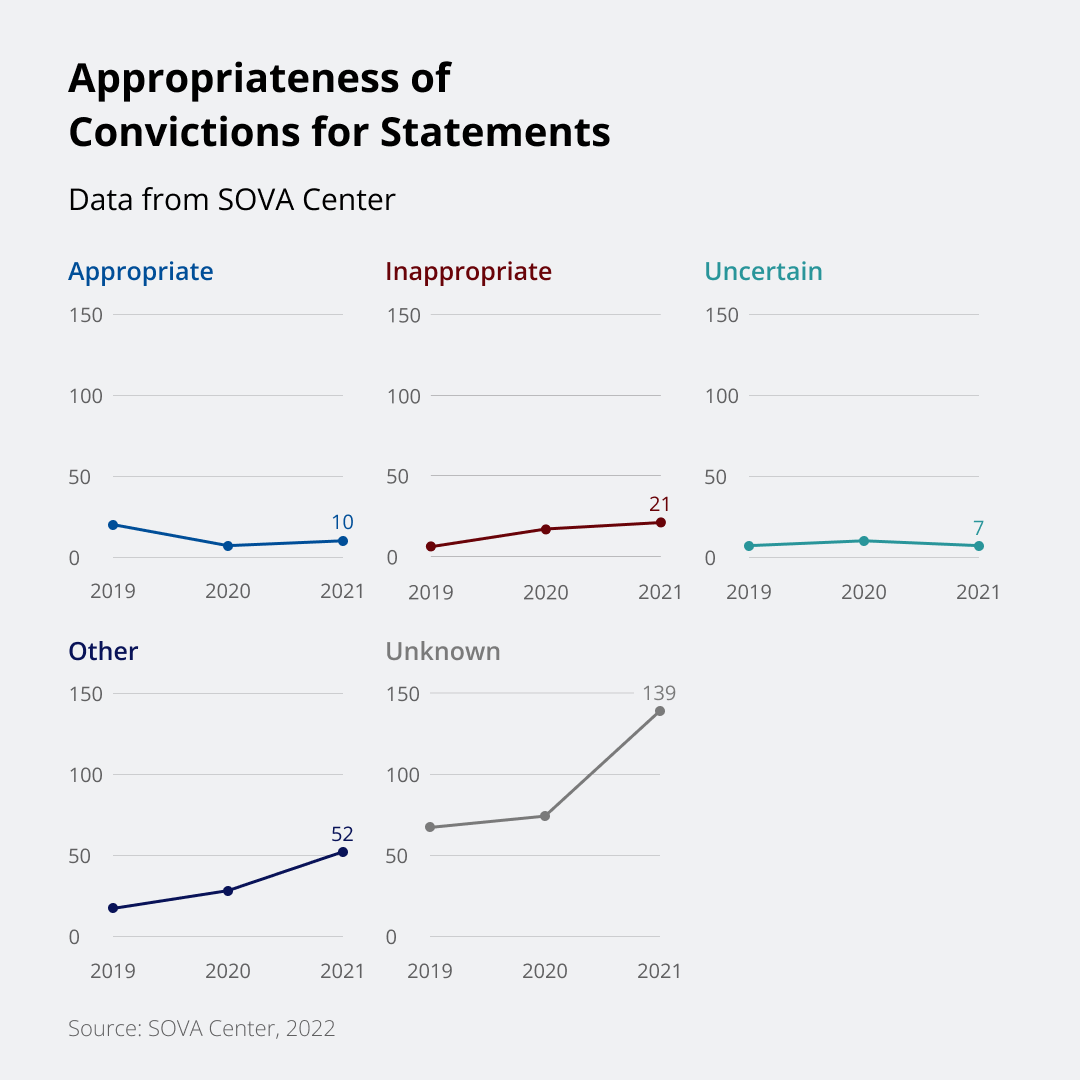

According to our incomplete data, the number of convictions for "extremist statements" (incitement to hatred, incitement to extremism or terrorism, etc.) has almost doubled in 2021 in comparison to 2020. SOVA Center has information about 204 sentences against 208 people in 64 regions of the country.[6] In 2020, we had information about 109 such sentences against 121 people in 47 regions. As is customary, we do not include in this report the sentences that we consider unlawful: in 2021, it was 20 sentences against 21 people.[7] Thus, this report includes the sentences that we consider lawful and appropriate, those whose appropriateness we doubt, and those about which we do not know enough to assess their lawfulness.

The statistics do not include any acquittals (none in 2021, one in 2020). In addition, we do not include in the statistics and record separately the instances of release from criminal liability with payment of court fines, an alternative introduced in Russian law in 2016. In 2021, we recorded three instances of such releases from liability with payment of court fines, and two in 2020.

Speaking about the overall statistics, our information about convictions is, regretfully, far from complete. According to the data posted on the Supreme Court website,[8] just in the first half of 2021, 212 people were convicted of "extremist statements," and this number includes only those for whom this was the main charge.[9] And this is much more than 132 people that were convicted during the same period a year earlier.[10] In this report, however, we use our own data, even though it includes only about one half of the total number of people convicted of "extremist statements," since the data of the Supreme Court do not permit a meaningful analysis to be carried out.

Since 2018, we have been using a more detailed approach to conviction classification.[11]

We deem appropriate those convictions where we have seen the statements, or are at least familiar with their contents, and believe that the courts have passed convictions in accordance with the law. In our assessment of appropriateness and lawfulness, we apply the Rabat Plan of Action on the prohibition of advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility, or violence, developed by the UN; it contains a six-part assessment of the public danger of public statements, supported by the by the Russian Supreme Court almost in its entirety.[12] The Rabat Plan of Action has also been endorsed by the UN Human Rights Council.

In 2021, we considered eight convictions against ten individuals lawful (six convictions against seven people in 2020). An example of such a lawful conviction is the November verdict under Article 282 of the Criminal Code to reserve colonel Mikhail Shendakov for publishing a video titled "Colonel Shendakov told a joke about Rosgvardia," where he directly called for violence against the Rosgvardia servicemen.[13] Given the colonel's popularity among retired military personnel, his repeated participation in the "Russian marches," and a large number of his followers, we agree that such calls can be dangerous.

Unfortunately, in the vast majority of cases – marked as “Unknown” (138 convictions against 139 people) – we are not familiar with the exact content of the materials and therefore cannot assess the appropriateness of the court decisions.

Convictions that we find difficult to assess fall under the category of “Uncertain” (six convictions against seven people): for example, we find one of the charges appropriate but not the other.

Our statistics in the “Other” category (52 convictions against 52 people) included individuals who called for attacks on government officials and those who were convicted under extremism articles of the Criminal Code more appropriately than not but whose prosecution cannot be classified as counteraction to nationalism and xenophobia.

According to SOVA Center data, Article 280 of the CC was used in the vast majority of the verdicts:[14] in 124 verdicts against 124 people. In 81 of these verdicts (82 people) this was the only charge. In some instances, it was combined with other charges, both "antiextremist" (Article 2821 (participation in an extremist group)) and ordinary criminal articles, for example, Article 228 of the CC (illegal acquisition of narcotic drugs) or Article 222 of the CC (illegal storage of firearms).

Article 282 (incitement to hatred) was applied in 22 convictions known to us against 22 people; for 16 of them this was the main charge. According to the investigative committees, all these people were charged with similar offenses under Article 20.3.1 of the Administrative Code (incitement to hatred) earlier in the year. Three people were convicted under the combination of Article 280 of the Criminal Code with Article 282 of the Criminal Code. One of them is the above mentioned Mikhail Shendakov, who was sentenced to two and a half years probation by the Krasnogorsk City Court of the Moscow Region in February for the published video "Surkov promised war to Donbass"; in this video, Shendakov again called for violence against law enforcement officers "across the country" and expressed his support for the shooter who had opened fire near the FSB building on December 19, 2019.

Article 3541 of the CC (rehabilitation of Nazism) was applied in 14 sentences against 14 people (and in one other case, which was dismissed); in 11 of the above, this was the main charge. In most cases, it was used to punish those who published statements and comments online (in almost all cases known to us – on VKontakte) containing “approval of Nazis’ actions, denial of the facts established by the verdict of the International Military Tribunal for the Prosecution and Punishment of Major War Criminals.” Two others, prisoners of colonies in Udmurtia and Khakassia, tried to convince other convicts "of the correctness of the actions of the Nazis," approved Nazism as an ideology, and one of them "spoke unfavorably about Victory Day." Parts 1 and 2 of Article 148 of the CC (public actions expressing obvious disrespect for society and committed in order to offend the religious feelings of believers) were applied in five sentences against seven people. Offensive inscriptions and images and a painted over icon above the church entrance in the village of Umba, Murmansk region, were qualified as such; in other cases, it was comments in a social network directed against "representatives of Islam" and Orthodox Christians, "which contained linguistic signs of insulting the religious feelings of believers" or calls for "hostile actions against the church."

Article 2052 of the CC (public calls to carry out terrorist activities) has gained popularity among law enforcement officers in recent years. According to the Supreme Court data, in the first half of 2021 a total of 89 people were charged under this article (73 in the first half of 2020). SOVA Center is aware of 64 sentences under Article 2052 of the CC handed down to 64 people in 2021 (not including wrongful convictions). In 40 cases, this was the only article applied in the conviction. In 10 other cases, it was applied in combination with Article 280 and in several cases – with other anti-terrorism articles of the Criminal Code, such as Part 1.1 of Article 2051 of the CC (involvement in terrorist activities).

The application of this article has become much more diverse compared to what it was five years ago, when this article was applied exclusively in convictions for radical Islamic propaganda. However, even this year 27 people have been convicted of radical Islamic statements, including calls to join ISIS or to support other Islamist terrorist organizations, including propaganda in penal colonies (at least 13 cases).

Four sentences were handed down for supporting the Christchurch (New Zealand) mosques terrorist attacks, committed on March 5, 2019.

28 sentences were handed down for inflammatory statements against the authorities, including five for supporting the terrorist attack at the Arkhangelsk FSB office by Mikhail Zhlobitsky and calls for repeat of such actions. Only one of these 28, a supporter of Russian National Unity (RNE) from Novosibirsk, can be identified as ultra-right.

In five cases, we do not know what exactly the calls for terrorism were.

Article 2801 of the CC was not used at all, and this is not surprising: at the beginning of the year, this article was reformed in the same manner as Article 282 of the Criminal Code: a similar Article 20.3.2 of the Administrative Code was introduced, and criminal liability under Article 2801 occurs only a year after administrative sanction.

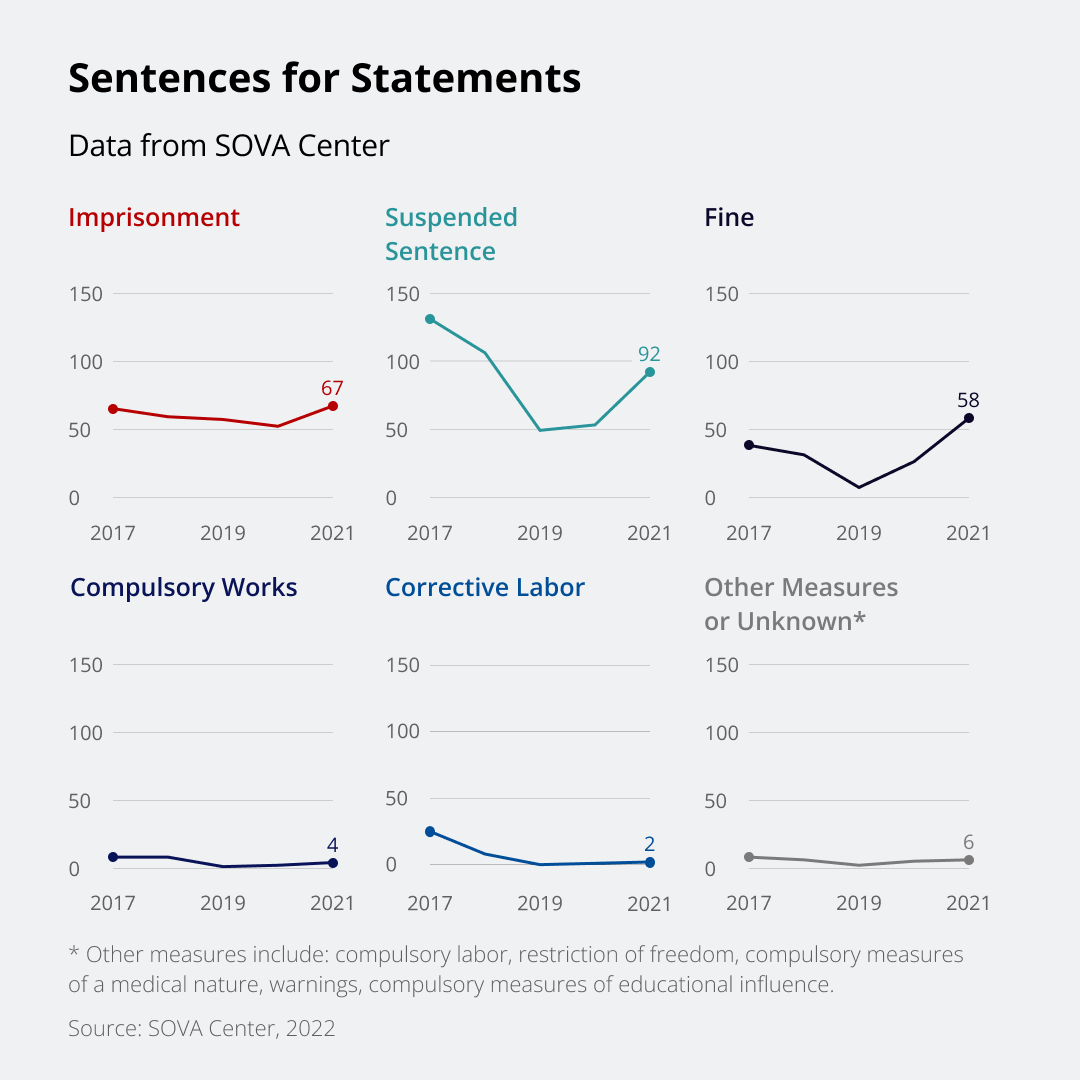

Penalties for public statements, excluding wrongful convictions, were distributed as follows:

- 62 people were sentenced to imprisonment;

- 90 received suspended sentences without any additional measures;

- 49 were sentenced to various fines;

- 1 was sentenced to corrective labor;

- 1 was sentenced to community service;

- 1 was sentenced to the restriction of liberty;

- 3 were sentenced to compulsory treatment;

- to 1 person, compulsory educational measures were applied.

In addition, two cases were terminated due to the expiration of the statute of limitations for criminal prosecution.

The number of people sentenced to imprisonment turned out to be significantly higher than a year earlier: in 2020, we reported 42 prison sentences.

Most of them received prison terms in conjunction with charges other than statements, including participation in extremist and terrorist groups and organizations. Ten were already serving prison time, and their terms were increased. Three were on parole.

On top of that, some of them were convicted under the “anti-terrorism” Article 2052 of the CC (see below); two people were sentenced under a combination of Articles 280 and 2052.

However, nine people received prison terms in the absence of any of the above-mentioned circumstances that reduce the chances of avoiding incarceration (or, perhaps, in some cases, we just do not know about them). The most notable of them was the "citizen of the USSR" from Krasnodar Krai Marina Melikhova.[15] On March 25, 2021, the Leninsky District Court of Krasnodar sentenced her under Part 2 of Article 280 of the Criminal Code to three and a half years in a penal colony for publishing a video on the VKontakte social network titled “On May 9, 2020, the Putin regime may come to an end! It depends only on us;" it contained statements which FSB officers considered a call for the violent overthrow of the regime.

In her address, Melikhova called on the existing regime “to voluntarily hand over everything it has stolen back to the people by May 9,” “to resign and hand power over to the indigenous peoples of Russia” and called on “‘the Russian men’ to take to the squares on May 9 and take ‘power into their own hands the way the Ossetians did.’” She added that on May 9, “there is a chance to overthrow the occupation regime,” which gave the people “the right to revolt against tyranny and oppression,” adding that “perhaps an uprising won’t be necessary.” In our opinion, Melikhova's address does contain calls for the violent overthrow of the government, but we consider punishment by imprisonment to be excessive.

A former camera operator for Anti-Corruption Foundation (recognized as a foreign agent in the Russian Federation) Pavel Zelensky was sentenced by the Tushinsky District Court of Moscow under Part 2 of Article 280 of the Criminal Code to two years in a general regime penal colony[16] for publishing two posts on Twitter expressing threats and hostile statements toward the highest authorities of the Russian Federation in relation to the suicide committed by Koza.Press editor-in-chief Irina Murakhtaeva (Slavina).

Less is known about the other convicts. In addition to those mentioned, five other people were convicted under Article 280 of the Criminal Code.

- In the Volgograd region, a court sentenced a local resident to one year in a settlement colony for publishing a comment on the open page of the "Russia against raising the retirement age" VKontakte community with calls "to commit active acts of violence against representatives of the authorities of the Russian Federation and Jews."

- In the Orenburg region, a court sentenced Victor Maltsev to one year in a settlement colony for posts on VKontakte in which he "called for the expulsion from Russia and for the extermination of" Jews.

- In the Astrakhan region, a court sentenced Rinat Galyaudinov to a year in a settlement colony for calls on Instagram "to carry out extremist activities against law enforcement officers."

- In Primorsky Krai, a court sentenced a local resident Vasily Oleinik to two years in a colony-settlement for a video with calls for the murder of "an unspecified number of law enforcement officers, motivated by political and ideological hatred and enmity."

- In the Tula region, a court sentenced Sergei Novikov to a year in prison for publishing certain materials on the VKontakte social network calling for xenophobic violence and violence against law enforcement officers.

One person was sentenced to imprisonment under Article 282 of the Criminal Code alone: in North Ossetia–Alania, a court sentenced a 23-year-old local resident to two and a half years in prison for "negative statements humiliating or degrading persons of a particular group that share one denomination, language, or origin" on VKontakte.

And finally, a court in Khabarovsk sentenced a 56-year-old resident of Amursk under Part 1 of Article 3541 of the Criminal Code to one year and two months in a strict regime colony for publishing on a social network "his photo with a red armband, a lead symbol of National Socialism" and comments "containing denial of the Holocaust and the responsibility of A. Hitler and the National Socialist German Workers' Party for the genocide of the Jewish people, as well as false information about the activities of the USSR during World War II."

In all these cases (especially in the case of punishment under Article 282 of the Criminal Code), the real prison terms seem to us to be an excessive punishment. What looks strange is the fact that in most of these cases, the imprisonment punishment is not applied for attacks on vulnerable groups, but for calls to attack law enforcement officers, that is, people protected by their special status, often armed and therefore unlikely to be in need of such harsh protective measures, at least not in situations of immediate threat (as, for example, during riots).

In comparison with the previous year, the situation has worsened: in 2020, we reported four convictions “for words only,” i.e. without the above mentioned aggravating circumstances that increase the chances of incarceration dramatically, 7 in 2019, 12 in 2018, 7 in 2017, 5 in 2016, 16 (the highest number) in 2015, and only 2 in each of the years 2013 and 2014.[17]

If we were to look at the share of prison sentences “for words only” (without any of the above-mentioned “aggravating circumstances”) to the total number of those convicted of statements in these years (leaving out the obviously unlawful sentences), we would see that in 2021 the share of such convictions was 4.3%. This parameter doesn’t seem to be showing a consistent trend: it was 3.6% in 2020; 6.8% in 2019, 5.5% in 2018, 2.8% in 2017, 2% in 2016, 6.5% in 2015, and slightly higher than 1% in years 2013 and 2014.

In the above calculations, we have excluded convicts under Article 2052 of the CC. Until the previous year, we did not include this article in our calculations, because firstly, the penalties under the “antiterrorism” article are predictably harsher, and, secondly, the degree of our awareness of the specific content of cases under this article is too low; besides, up until 2018 the vast majority of sentences under Article 2052 of the CC had nothing to do with countering incitement to hatred.

In 2021, 13 people were sentenced to imprisonment under Article 2052 of the CC without the circumstances listed above (in 2020, we reported 8 such sentences). If we are to believe the prosecutor's office, the people convicted in 2021 were calling to join ISIS or other radical Islamic organizations, approved the Christchurch terrorist attacks, and supported the bombing of the Arkhangelsk FSB office. However, we do not have information about the exact content of their publications, the size of their audience, and their popularity. Comparing with the practice of applying Article 280 (see above), we are unable to determine why similar statements were sometimes qualified as calls for extremist and sometimes as calls for terrorist actions.

In 2021, the proportion of suspended sentences remained virtually the same at 43.6% (90 out of 206) compared to the 45% of the previous year. The share of the convicts whose sentences did not involve prison time (actual or suspended), i.e. those sentenced mostly to fines, has declined again. This is the fifth year that we are seeing this trend.

Almost all the sentences mention additional bans on activities related to the administration of websites and on the use of the Internet in general. In one case, a ban on working with children was imposed. In five cases, the confiscation of the "instruments of crime" (routers, laptops, mobile phones) was reported.

As is becoming a tradition, the vast majority of sentences were imposed for materials posted on the Internet – 187 out of 204, or 91%, compared to 87% in 2020.

As far as we were able to understand from the reports about the sentences, these materials were posted on:

- social networks – 138 (74 on VKontakte, 1 on Facebook; 6 on Instagram; 2 on Odnoklassniki; 1 on TikTok; 1 on Twitter; 53 on unidentified social networks[18]);

- messengers – 6 (2 in Telegram; 4 in WhatsApp);

- YouTube – 3;

- public chats – 2;

- online media – 6;

- on the Immortal Regiment website – 4;[19]

- unspecified online resources – 28.

The types of content are as follows (different types of content may have been posted in the same account or even on the same page):

- comments and remarks, correspondence in chats – 59;

- other texts – 60;

- videos – 27;

- images (drawings and photographs) – 10;

- audio (songs) – 6;

- administration of groups and communities – 2;

- unspecified – 26.

The breakdown reflected in the first list has remained roughly the same for the past ten years (see previous annual reports on this topic, as well as reports on the persecution for extremism on the Internet).[20] The second list reflects the diversity of the formats of incriminated statements, first noted in 2020:[21] they include many comments and remarks posted on social networks, whereas previously it was mainly videos and images.[22]

The number of convictions for offline statements (17 for 19 people) turned out to be roughly the same as in 2020 (12 for 20 people). They were distributed as follows:

- propaganda in prison targeting fellow prisoners – 10 (7 – verbal propaganda, 3 – showing videos);

- propaganda in the army – 1;

- shouts during attacks – 1;

- propaganda during lessons – 1;

- speech at a rally – 1;

- distribution of prohibited literature – 1;

- graffiti – 2 sentences (to 4 people).[23]

Interestingly, a little more than half of those convicted of offline propaganda carried it out in prisons. As we have written many times before,[24] we have doubts about the lawfulness of the sentences for terrorist propaganda given to those who are already in prison. There are certainly quite a lot of individuals prone to violence among prison population; therefore, any promotion of hatred in prison is, by definition, dangerous. However, it is not clear whether the key parameter in the articles of law applicable to statements – the audience size – has been taken into account: it is hardly possible to consider a conversation in a narrow circle of several cellmates to be public.

The issue of propaganda in the army is more complicated: the possibilities there are similarly limited, but access to weapons raises the likelihood of serious consequences.

We tend to consider sentences for speaking at rallies or disseminating propaganda in educational institutions lawful and appropriate (depending on the size of the audience). However, we doubt the need for criminal prosecution for individual graffiti on fences and buildings.

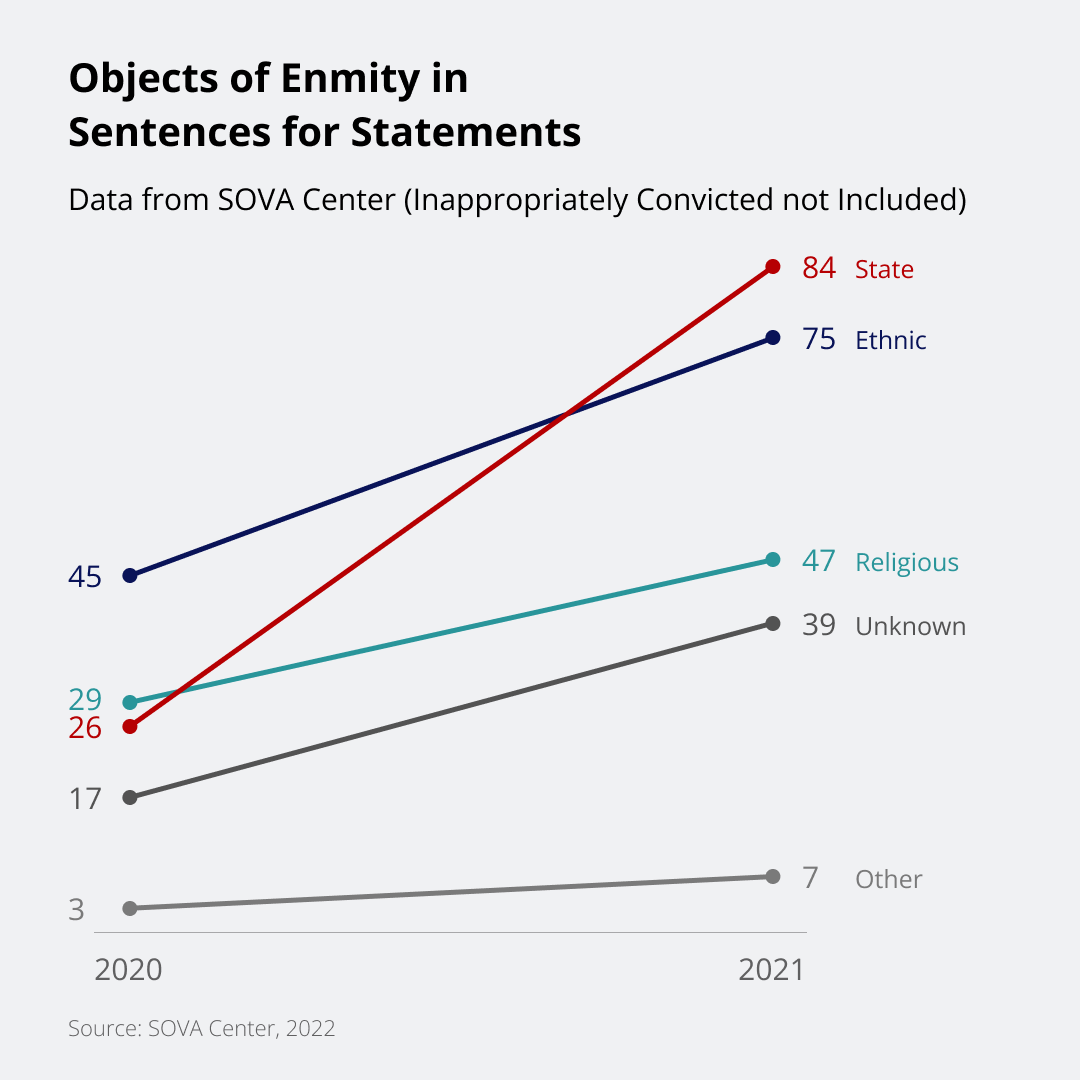

In the vast majority of cases, we were unable to get access to the materials that were the subject of the trial; still, based on the descriptions provided by the prosecutor's offices, investigative committees, and the media,[25] we identified the following targets of hostility in the sentences passed in 2021 (some of the materials expressed hostility toward several groups):

- ethnic enemies – 75, including: Jews – 17; natives of Central Asia – 8; natives of the Caucasus – 10; Kalmyks – 1; Ingush – 1; Russians – 4; Ukrainians – 1; Ossetians – 1; dark-skinned people – 1; non-Slavs in general – 4; unspecified ethnic enemies – 27;

- representatives of the state – 84, including: public officials – 22; law enforcement officials – 16; top politicians, senior state officials – 12; members of the United Russia party – 2; FSB officers – 9; police and security forces (siloviki) – 18; Presidents of the Russian Federation (former and present) – 1; Kuzbass government – 1; bailiffs – 1; military – 2;

- religious enemies – 47, including: Christians – 5; clergy – 1; Muslims – 18; followers of Judaism – 1 (separately from Jews); infidels from the point of view of Islam (romanticizing militants, calls to join ISIS and jihad) – 14; the motive of religious hatred for an unspecified object – 8;

- people who drink alcohol – 1;

- communists – 1;

- anti-fascists – 1;

- capital city residents – 1;

- senior management of Russian businesses – 1;

- athletes – 1;

- children – 1;

- unknown – 39.

As can be seen from the above data, the situation has changed significantly compared to previous years: the three largest groups of enemies remained the same – ethnic, religious, and state, but whereas the shares of the first two have changed little, the representatives of the state, which used to equal half the number of ethnic enemies in this rating, took the first place in 2021. That is, sentences were passed most often for statements against the authorities and their repressive apparatus, although the total number of criminal prosecutions for ethnic and religious xenophobia still outstrip prosecutions for political enmity: 122 against 86 cases. It is noteworthy that among the cases known to us, there was only one verdict for offline political hostility.

For Participation in Extremist and Terrorist Groups and Banned Organizations

In 2021, we have information about 20 verdicts against 28 offenders under articles 2821 (organizing an extremist group), 2822 (organizing the activity of an extremist organization), 2055 (participation in the activities of a terrorist organization), and 2054 of the CC (participation in the activities of a terrorist group), which is slightly less than in 2020, when we wrote about 14 sentences against 36 people. These numbers do not include inappropriate convictions, whose number in the past year was again much higher than in other categories: we have deemed inappropriate 95 sentences against 164 people.[26] If we look at the total number of convicts under these articles, then according to both the Supreme Court[27] and our data (and we have information about a little more than half of the sentences), we can say that the number of convicts was about one third higher in 2019 and 2021 than in 2017 and 2018. At the same time, our data for 2021 again show an increase of about one third, while the extrapolation of the Supreme Court data for the first half of the year would suggest even a slight decrease. Perhaps our data have become more complete, but it should still be assumed that extrapolation in this case significantly underestimates the actual number of convicts per year. And indeed, even according to our data, an acceleration is visible in the second half of the year, regardless of the lawfulness of the sentences.

In 2021, Article 2821 of the CC was applied in six verdicts against 10 people. As is customary, it was primarily applied against members of ultra-right groups.

Two members of Black Bloc, Artem Vorobyov and Dmitry Nikitin from Moscow, and three members of an ultra-right community from the Kirov region, were convicted of participating in the extremist community (and xenophobic attacks).[28] Interestingly, they all received suspended sentences.

In Ryazan, a court sentenced local far-right activists Artem Smorchkov and Yuri Lunin to six years of probation and one year and three months in a strict-regime penal colony.[29] According to the prosecutor's office, they carried out several attacks on anti-fascists, filmed the attacks, and posted the videos online along with texts promoting ideological violence.[30]

In Tambov, the garrison military court found Sergeant Egor Metlin guilty under Part 1 of Article 282.1 of the CC in combination with Part 3 of Article 30 of the CC (attempt to create an extremist community) and fined him 600 thousand rubles.[31] According to investigators, Metlin in conversations with colleagues “called for xenophobic violence and also distributed banned literature” and planned to set fire to houses of “representatives of non-Slavic nationalities.” On July 27, 2019, he was detained with two bottles of flammable mixture and arrested.

The other two sentences were directly or indirectly related to Ukraine, which is atypical for this article. Usually, Article 2822 has been applied in connection with Ukraine.

In Crimea, in the case of complicity in the creation of an extremist community (Part 3 of Article 33 of the CC and Part 1 of Article 2821 of the CC) and a knowingly false report about the mining of the Crimean Bridge (Part 3 of Article 207 of the CC), Ukrainian citizen Alexander Dolzhenkov received six years in prison. It is unclear which actions the verdict on the creation of an extremist community is related to.

In the Rostov region, Sergei Shurygin, a regional coordinator of the Left Front political movement, got 6.5 years of suspended sentence and additional punishment in the form of restriction of freedom for a year, as well as a ban on engaging in activities related to the management and organization of the work of political, religious, and public organizations and associations for three years under Parts 1 and 1.1 of Article 2821 (organization of and recruitment into an extremist community) and Part 2 of Article 280 of the CC. Shurygin has created and was managing the Union of the World Liberation Movement People's Brotherhood AllatRa (The Union of the Peoples of the Sun and the Peoples of the Crescent), “based on the ideology of the foreign religious association International Social Movement AllatRa.” The movement was created on the basis of the new Ukrainian organization Allatra, whose central ideological element is the fight against “world Zionism.” It is also characterized by Stalinism and the Messianic idea that the Russian nation should save humanity and unite the peoples of the world around itself.

Article 2822 of the CC was invoked in ten sentences against 13 people.

In Stavropol Krai, Yuri Korobov was sentenced to two years and 10 months of imprisonment in a high-security penal colony, with a restriction of freedom for a period of 10 months for funding and participating in the activities of the Ukrainian organization Praviy Sektor (Right Sector), banned in Russia.

Six people in the Tula region, Stavropol Krai, Volgograd, and Mari El were sentenced for terms ranging from two-year suspended sentence to three years in a strict regime colony for participating in the activities of the banned Union of Slavic Forces of Russia (USSR).[32] A "citizen of the USSR" from Mari El was sent for compulsory treatment. All these "citizens of the USSR" from different regions convened and held meetings and disseminated the community’s ideology. Some sold passport inserts “attesting citizenship of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.” One “citizen of the USSR” from Stavropol propagandized his views in his correspondence with local authorities, thereby following in the footsteps of another banned exotic association Spiritual-Ancestral Empire Rus.[33]

Five people in Dagestan, Adygea, and Samara were sentenced to terms from one and a half to seven years in a penal colony for involvement in At-Takfir Wal-Hijra, recognized as extremist in Russia. It is reported that they attended meetings, distributed literature, recruited new participants, "planned to commit a number of serious crimes, and then go to Syria and join the ranks of one of the international terrorist organizations."[34]

In Adygea, a local resident was found guilty of participating in the A.U.E. criminal subculture, which for some reason is recognized as an extremist organization,[35] and received a 2.5-year suspended sentence with restriction of liberty for six months and a 2.5-year probation. According to the prosecutor's office, he promoted a criminal lifestyle, the A.U.E. agenda, and hostility toward representatives of the authorities, and posted A.U.E. symbols and slogans on social networks.

We are not aware of any verdicts under Article 2054in 2021. Article 2055 was applied against two supporters of ex-colonel Vladimir Kvachkov. Yuri Yekishev was sentenced to 15 years and Pavel Antonov to 10 years in a high-security penal colony.[36] Both were prosecuted for their participation in the banned movement Minin and Pozharsky People's Militia (NOMP)[37] and the preparation of an armed attack on a police station. During searches, leaflets, propaganda materials, Osa handguns and Saiga rifles were found in the suspects’ apartments.

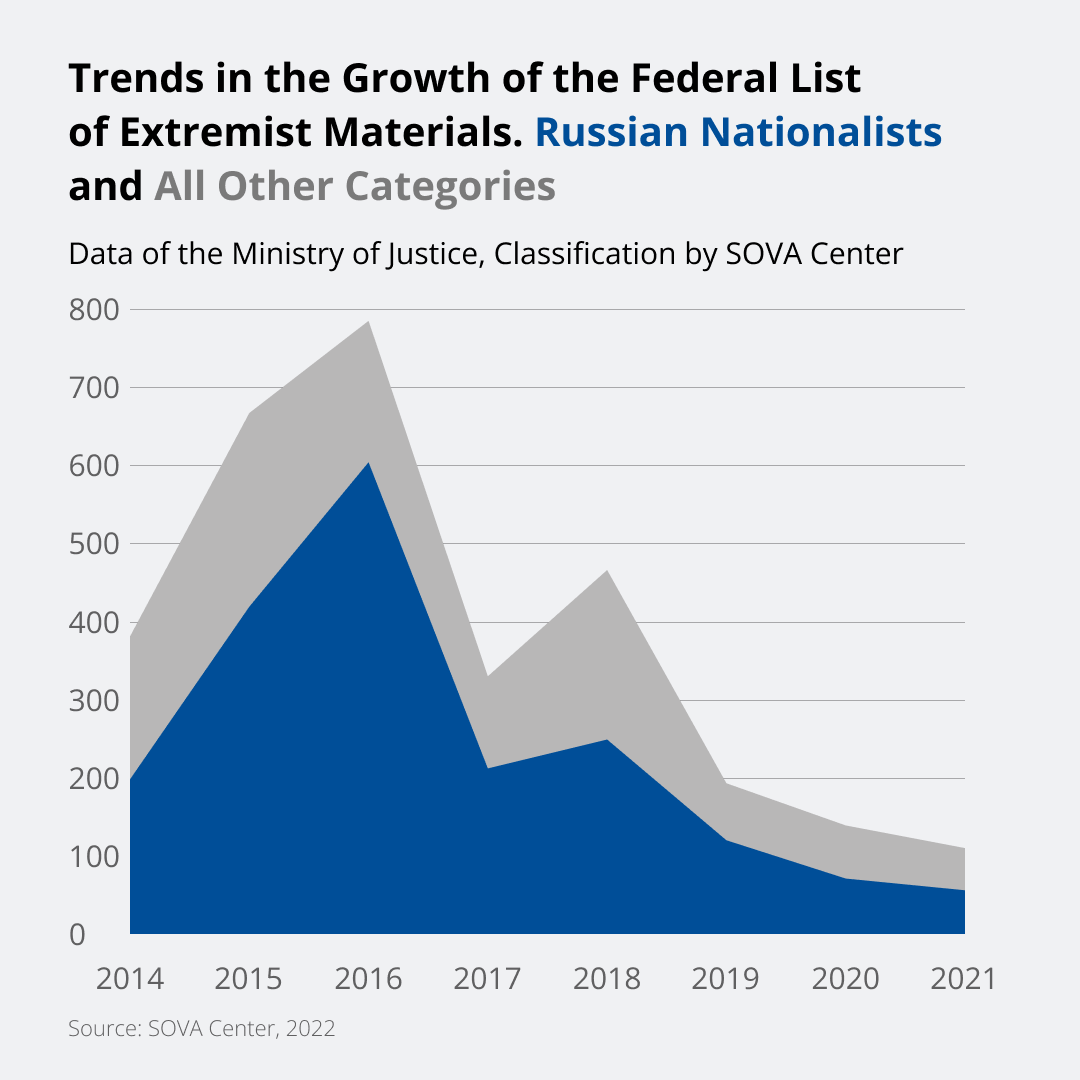

Federal List of Extremist Materials

In 2021, the Federal List of Extremist Materials was expanding somewhat slower than in 2020: it was updated 23 times with 110 entries (139 in 2020). Thus, the total entries grew from 5144 to 5253.[38]

New entries fall into the following categories:

- xenophobic materials of contemporary Russian nationalists – 56;

- materials of Islamic militants and other calls for violence by political Islamists – 8;

- other Islamic materials – 10;

- materials of Orthodox fundamentalists – 1;

- materials by other peaceful worshippers (writings of Jehovah's Witnesses) – 1;

- extremely radical materials from Ukraine – 3;

- anti-government materials inciting to riots and violence – 12;

- works by classical fascist and neo-fascist authors – 2;

- parody banned as serious materials – 6;

- people-haters’ materials – 1;

- A.U.E. materials – 8;

- fiction – 1;

- unidentified materials – 1.

As in the previous years, the majority of the new entries are Russian nationalists’ materials, although the number of new entries in this category is lower this year. New categories that appeared in 2021 are materials promoting A.U.E. and the ideology of people-hate. Other than that, the categories have not changed compared to previous years, but a significant decrease is evident.

At least 88 entries out of 110 refer to online content: video and audio clips, long texts, and images. Offline sources include books by Russian nationalists and Salafi Muslim authors and a fiction book about the rapes of German women by Soviet soldiers.

However, for a number of entries, it is unclear where the banned materials were published. This mainly concerns songs or videos: the entry contains the title of the material and, at best, its author. For example, entry 5165, described as “We are Here” (an audio recording of a song by the Yarovit band), provides no publication data. The song “White Power” by the Seytar band is included in the list twice: as an audio recording (entry 5209) and as a text (entry 5210). No source is provided in either entry. In any case, we are not sure which of the following descriptions is more correct: the one that contains just the title of the song or the band or the one that provides the description “freely available on the Internet” (entries 5250 and 5251). While in 2021 slightly fewer grammatical errors were observed than before, bibliography rules are still not being followed.

As is frequently the case, some entries were described in such a way that it is not clear what they mean exactly. For instance, entry 5169 is described as “We the Mujahideen the Army of Allah…” (audio recording). A search for this title returns multiple different audio recordings, and which of them is prohibited remains a mystery.

As usual, some of the materials added to the list are those obviously unlawfully recognized as extremist: in 2021, not less than 19 such entries were recorded (compared to 25 in 2020).[39]

The Banning of Organizations as Extremist

In 2021, nine organizations were added to the Federal List of Extremist Organizations published on the website of the Ministry of Justice (compared with five in 2020).

Slightly more than half of the organizations newly added to the list are nationalist.

The Nation and Freedom Committee (KNS) was recognized as extremist by the Krasnoyarsk Regional Court on July 28, 2020. KNS was founded in September 2014 by Vladimir (Basmanov) Potkin and was one of the main fragments of the banned association Russkie (Russians).[40] The entry contains a detailed description of the organization's symbols, including the emblem and the flag of the KNS, which is only the second time such details have been entered.

Russian Patriotic Club-Novokuznetsk / RPC was recognized as extremist by the Central District Court of Novokuznetsk, the Kemerovo region, on December 7, 2020. The club, founded in early 2012, had several dozen members; they distributed anti-migrant materials, picketed the construction of mosques in the city, fought against the construction of a synagogue and against organizations dealing with adaptation of migrants, opposed an LGBT festival, and collected money for neo-Nazi prisoners.

Two radical fan organizations were also added to the list.

The W.H.С. organization (White Hooligans Capital, Belye Khuligany Stolitsy, White Hardcore Cats, SIBERIAN FRONT, Sibirsky Front) was recognized as extremist by the Central District Court of Barnaul on September 16, 2020. The group, founded by Yevgeny (Ratibor) Dergilev in 2015, included 25–30 hockey fans. They organized sports training sessions in Barnaul, participated in mass fights with other fans, and attacked anti-fascists. Some members of the Siberian Front were charged with administrative and criminal offenses.[41]

A football fans group Irtysh Ultras (Brutal Jokers, Fluss Geboren) was recognized as extremist by the Central District Court of Omsk on November 27, 2020 . The group, founded in January 2017, consisted of 26 members who wore military-style clothes but rejected military service and celebrated Hitler's birthday every year. On VKontakte, the Irtysh Ultras group had 525 participants; the group was also present on Instagram.[42]

Two more organizations that have joined the list are quite exotic and make one question the mental adequacy of their participants.

A pagan movement Siberian Sovereign Union (also known as Union of Glorious Clans of Rus, Slavic Warriors Brotherhood, Siberian-Ukrainian Movement, Spiritual-Political Movement “Liberation”) was recognized as extremist by the Supreme Court of the Altai Republic on March 19, 2021. The organization Slavic Warriors Brotherhood, founded by Alexander (Svyatozar) Budnikov in 2006, was part of the spiritual and political community Rus Rodoslavnaya and advocated the separation of Siberia from the Russian Federation and the creation of an independent Siberian republic, as well as the creation of the spiritual and cultural center AzGrad in Altai. Its branches, numbering more than 20 members each, existed in the Novosibirsk region and other Siberian regions. Budnikov himself has already been tried for xenophobic agitation.[43]

The Council of Citizens of the USSR of Prikubansky District of Krasnodar was recognized as an extremist organization by the Prikubansky District Court of Krasnodar on June 29, 2021. The Council was founded in June 2019 by Marina Melikhova, already mentioned in this report (see the section Prosecution for statements). In addition to the issue that is key for "citizens of the USSR" – the illegitimacy of the authorities of the Russian Federation, the Council members discussed the priority that should be given to "indigenous peoples," the invalidity of Bank of Russia notes, the harm of the law on priority development areas, according to which the Russian territories are, allegedly, to be distributed to foreigners, etc. The Council especially abused anti-Semitic rhetoric. Members of the Council have repeatedly been prosecuted in criminal cases.[44] In 2020, "citizens of the USSR" from Krasnodar, 60-year-old Alexander Dudarenko and 70-year-old Zoya Malova, who ordered the murder of Yuri Tkach, the head of the Jewish community of Krasnodar, were detained. The perpetrator was promised a high post in the Citizens of the USSR organization as a reward for assassination. An operative responded to the ad and met with the customers, who handed him a boxcutter, a mask, and a stocking. The police staged the assassination and sent photos to the customers. After that, the organizers of the murder were detained. In December 2021, the Pervomaisky District Court of Krasnodar sentenced Zoya Malova to six years in prison for attempted murder.

We find other bans unlawful. Khakassian Regional Public Organization for Spiritual and Physical Self-Improvement of a Person under the Great Falun Law “Falun Dafa” was recognized as extremist in November 2020.[45] Three pro-Navalny organizations – Anti-Corruption Foundation, the Citizens' Rights Protection Foundation and “Navalny's headquarters” – were declared extremist by the Moscow City Court on June 9, 2021.[46]

Thus, as of February 10, 2021, the list includes 89 organizations,[47] whose activity is banned by court order and continuation thereof is punishable by Article 2822 of the CC.

The list of terrorist organizations published on the website of the FSB was updated with three new entries in 2021 (none in 2020).

On May 21, 2021, the Supreme Court declared NS/WP (National Socialism / White Power, NS/WP Crew Sparrows, Crew / White Power) a terrorist organization. Sounds intimidating, but from this list of names it is impossible to understand which organization the court meant. According to the Prosecutor General's Office, NS/WP has existed in Russia since 2010 as a network movement, whose leaders have organized at least 18 neo-Nazi groups. Indeed, the abbreviation NS/WP was and still is used by many far-right groups; there is no doubt that personal or even structural ties exist between them, but not necessarily the ties that interconnect them all. We do not have sufficient information on this matter (and we believe that neither does the Prosecutor General's Office).

The most notorious of these groups was NS/WP Nevograd, whose verdict was passed in St. Petersburg in June 2014. And Sparrows Crew (not “Crew Sparrows” as written in the court decision) is a Yekaterinburg group that published online and, possibly, filmed its own videos of xenophobic attacks. The connection between these two groups is unknown to us.

A little later, on October 25, this time based on a claim of the St. Petersburg prosecutor’s office, not the Prosecutor General's, a group with a similar name, Nevograd (Nevograd-2, BTO-Nevograd, First Line Nevograd) was recognized as extremist;[48] Nevograd has not yet been included in the list on the Ministry of Justice website. Judging by the claim of the prosecutor's office, this case was against several St. Petersburg neo-Nazi groups connected with Andrei Linok in one way or another.[49]

The impression one gets is that a decision was made to ban not a specific NS/WP organization, but the entire popular “brand,” which will make it possible in the future to bring criminal charges against supporters of various far-right groups that have used this “brand” in the past. This is not the first time such a method is being used: recall the prohibition of the A.U.E. subculture; perhaps the banning of At-Takfir wal-Hijra is used in the same way.

NS/WP may be too broad a name, but “The terrorist community created by V.V. Maltsev from among the participants of the Interregional Public Movement Artpodgotovka" is, on the contrary, extremely specific and strangely narrow. The decision to ban it is based on the verdict in the case of a terrorist group, issued by the 2nd Western District Military Court on July 18, 2020 and entered into force on July 7, 2021. This decision also requires clarification. The Artpodgotovka movement itself was recognized as extremist by the Krasnoyarsk Regional Court on October 26, 2017, and it is included in the Federal List of Extremist Organizations. This may have caused confusion, leading some media to mistakenly report that Artpodgotovka was moved from the list of extremist organizations to the list of terrorist ones. However, this is not the case.

On July 18, 2020, three Artpodgotovka supporters (Yuri Korny, Andrei Keptya, and Andrei Tolkachev) were sentenced for attempting to set fire to pallets of hay left on Manezhnaya Square in Moscow after a city fair on October 12, 2017.[50] They were convicted not only under Paragraph A of Part 2 of Article 205 of the Criminal Code in combination with Part 1 of Article 30 of the Criminal Code (preparation of a terrorist act by a group of persons), but also under Part 2 of Article 2054 of the CC. According to anti-terrorism legislation, the establishing of the existence of a terrorist group should entail banning it as a terrorist organization and adding it to the list on the FSB website, with the possibility of prosecution for attempts to continue the activities of this organization under Article 2055 of the Criminal Code. According to the court decision of July 18, 2020, this group included seven people, three of whom were convicted, and four more, including Artpodgotovka leader Vyacheslav Maltsev, went into hiding. Thus, the entire Artpodgotovka movement has never been declared terrorist; only a small group of people was given this status. Of course, the question is whether this particular group continued to exist after 2017 and what can be considered a continuation of its activities. This is far from the first case when a group that has long and definitely ceased to exist is added to one list of banned organizations or another (the most extreme case is perhaps that of Noble Order of the Devil),[51] and we are unaware of any further cases under Articles 2055 and 2822 where any of these groups are mentioned.

Finally, in 2021, the group Jamaat Red Plowman was added to the list after it was recognized as terrorist by the Krasnoglinsky District Court of Samara in July. In 2016, more than 50 people were detained on suspicion of involvement in the activities of this organization after an explosive device was found in a prayer house. In 2019, FSB officers detained 16 more members of the jamaat in Ivashevka. Some of those detained were convicted, and some of the literature confiscated from the prayer house was recognized as extremist.

Sanctions for Administrative Offences

The number of those punished under administrative “extremism” articles, according to our rather incomplete data, increased in 2021. According to the Supreme Court data, if we extrapolate the numbers for the first half of the year, there was an increase of about 20%, which is twice as high as the increase in 2019.

The data provided below do not include the decisions we deem obviously inappropriate.[52]

Article 20.3.1 of the CAO (incitement to national hatred) was introduced after the amendments that introduced the mechanism of administrative prejudice to Part 1 of Article 282 of the CC were passed in 2018. Article 20.3.1 of the CAO is identical in content with Part 1 of Article 282 of the CC, but the administrative penalties are incomparably milder than the criminal ones.

According to the SOVA Center’s data, 168 rulings were passed under Article 20.3.1 of the CAO in 2021 (at least one was against a minor), while in 2020 we reported 126 rulings. According to the data of the Supreme Court, in the first half of 2021 alone, 461 persons were punished.[53]

The vast majority were punished for posts on social networks (primarily on VKontakte but also on Odnoklassniki, Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, in a Telegram chat), on WhatsApp (in a large group), YouTube, and TikTok with comments, texts, videos, and images with xenophobic insults against natives of Central Asia and the Caucasus, Roma, Russians, Ukrainians, Jews, Kazakhs, Tatars, Yakuts, Chinese, dark-skinned, Arabs, non-Slavs, and other ethnic others; also against Orthodox Christians, Orthodox priests, Muslims, homosexuals, police officers, government officials, deputies of the State Duma, bailiffs, emergency medical personnel, Ministry of Emergency Situations personnel, and Gazprom employees.

Three people were punished for offline offenses, such as shouting insults at neighbors. Among them were two residents of Moscow, who in April 2021 attacked two girls from Buryatia, Saryuna Rinchinova and Irina Darnaeva, in one of the Moscow courtyards, screaming xenophobic insults.[54]

The majority were fined for between five thousand and 10 thousand rubles. 11 people were arrested for terms between five and 15 days, eight were punished with community service, one received a warning.

The most famous of those punished was Vsevolod Moguchev, an associate of the infamous former schema-hegumen Sergius (Romanov), in the past the leader of the Yekaterinburg branch of the far-right Party for the Protection of the Russian Constitution Rus and of the local branch of the banned Movement against Illegal Immigration, and later the head of the regional squad of the youth organization Nashi and a member of the LDPR. Moguchev was arrested twice in one year. First, he received 15 days of administrative arrest for publishing a video titled “Who is Preparing Slavery in Russia" with a sermon by Father Sergius, which contained xenophobic statements, on his personal VKontakte page in June 2020, and on January 25 he received another 15 days of administrative arrest for publishing another video on YouTube.

In 2021, we have information about 166 individuals punished under Article 20.3 of the CAO (propaganda or public display of Nazi paraphernalia or symbols, or paraphernalia or symbols of extremist organizations, or other symbols whose propaganda or public display are banned by federal law), including seven counts against one person, two against one person, and at least five charges against minors. In 2020, we reported 158 people punished under this article. But whereas our data does not indicate growth, the statistics of the Supreme Court hints at a very significant increase: in the first half of 2021, this article was used to impose penalties in 1704 (one against a legal entity, one against an official, four against entrepreneurs without legal entities), compared to 1052 in the first half of 2020.

114 of those punished under this article posted images of Nazi symbols (mostly swastikas), runes, and in some cases symbols of such banned organizations as the Northern Brotherhood and ISIS on social networks, mainly on VKontakte, but also on Odnoklassniki, Instagram, in Telegram, and in a WhatsApp group.

52 people were punished for offline offenses.

The number of inmates punished for displaying their Nazi tattoos, has increased. In 2021, we are aware of 46 such instances (and one other individual displayed not a swastika, but an embroidery with Nazi symbols), compared to 27 we reported in 2020.

Four people displayed their tattoos outside of prison. In addition, one person painted a flag of the Third Reich on the facade of a building, and another displayed a ring with a swastika.

The majority of the offenders under Article 20.3 were fined for between one thousand and three thousand rubles. At least five were punished with administrative arrests of between three and 15 days.

We are aware of 130 persons punished under Article 20.29 of the CAO (production and dissemination of extremist materials), at least two of them minors. In 2020, we reported 162 persons. According to the Supreme Court statistics, in the first half of 2021, Article 20.29 of the CAO was used to impose 764 sanctions (four against officials, three against entrepreneurs without legal entities), compared to 856 in 2020.

Most of the offenders paid moderate fines between one thousand and three thousand rubles. At least two were placed under administrative arrests.

In the majority of the cases, the offenders were punished for posting on social networks VKontakte, Odnoklassniki, Instagram, and in a WhatsApp group nationalists’ materials, such as 88 Precepts by David Lane; songs by bands popular among the neo-Nazis (Kolovrat, Russky Styag (“Russian Flag”), Div, 25/17, Buchenwald Flava, Shmeli (“Bumblebees”), Korrozia Metalla (“Corrosion of metal”)); books by Nikolai Levashov, the pamphlet “The Prophecy of the Qams,” the Neo-pagan film “Games of the Gods,” the poem “Christian slavery,” and radical-Islamist materials, for example, songs by the singer-songwriter of the armed Chechen resistance Timur Mutsurayev. Several people have published symbols of ISIS and other radical Muslim organizations. In at least six cases, CDs were confiscated as objects of an administrative offense.

One person was fined for selling books that are on the Federal List of Extremist Materials in the hall of a shopping center. Another person was charged with storing prohibited literature “with the purpose of selling it.”

At least 13 people faced sanctions under combined articles 20.3 and 20.29 of the CAO in 2020. Two were punished under combined Articles 20.3.1 and 20.29 of the CAO. Two – under a combination of Articles 20.3 and 20.3.1 of the CAO. Three people were punished under a combination of all three articles (20.3.1, 20.3, and 20.29). All of them were fined.

In addition, at least two people were fined under the new article 20.3.2 of the Administrative Code (public calls for separatism). There was no data on this article in the statistics of the Supreme Court for the first half of the year.

We have covered the decisions that we consider more or less lawful. At the same time, we have information about 22 more instances of inappropriate penalties under Article 20.3.1 of the CAO, 47 under Article 20.3 of the CAO, 83 under Article 20.29 of the CAO, and 6 under Article 20.3.2 of the CAO. Thus, for 466 lawful and appropriate rulings (including those we are unable to assess) there are 158 inappropriate ones, and the share of the latter (about 34%) has increased again in comparison with the previous year (in 2020, we recorded 103 inappropriate rulings and 446 appropriate, or 23%).

[1] Our work on this issue is supported by the Norwegian Helsinki Committee and Berta International.

On 30 December, 2016, the Ministry of Justice has forcibly listed SOVA Center as “a non-profit organization performing the functions of a foreign agent.” We disagree with this decision and have filed an appeal against it. The author of this report is a member of the Board of SOVA Center.

[2] Natalia Yudina. The State Has Taken up Racist Violence Again: Hate Crimes and Counteraction to Them in Russia in 2021 // SOVA Center. 2022. 31 January (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2022/01/d45715/).

[3] Maria Kravchenko. Inappropriate Enforcement of Anti-Extremism Legislation in Russia in 2021.

[4] In Russia, the number of people convicted of extremism has almost doubled in one year // TASS. 2022. 9 February (https://tass.ru/obschestvo/13658383).

[5] According to the Criminal Code, crimes of extremist orientation are crimes committed with the motive of hatred, as defined in Article 63 of the Criminal Code. The law, however, does not establish a list of articles of the Criminal Code that belong to this category.

[6] Data as of 22 February 2022.

[7] Kravchenko, Inappropriate Enforcement of Anti-Extremism Legislation in Russia in 2021.

[8] Consolidated statistics on the state of criminal record in Russia for the first half of 2021 // Website of the Judicial Department at the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation (http://cdep.ru/index.php?id=79&item=5895).

[9] According to the Supreme Court data, the highest number of criminal convictions for propaganda in the first half of 2021 were issued under Article 280 of the CC (incitement to extremist activities): in 6 months, 124 people were charged. It is followed by Article 2052 of the CC (propaganda of terrorism) with 89 convicted in the first half of 2021. 8 people were convicted under Article 3541 (rehabilitation of Nazism). 6 people were found guilty under Part 1 of Article 148 of the CC (insults of believers’ religious feelings). 2 were convicted under Part 2 of Article 148. Article 282 of the CC (incitement to hatred) was used in guilty verdicts against 13 people in the first half of 2021.

For more information see: Official statistics of the Judicial Department of the Supreme Court on the fight against extremism for the first half of 2021 // SOVA Center. 2021. 21 October (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2021/10/d45144/).

[10] Consolidated statistics on the activity of federal courts of general jurisdiction and magistrate courts for the first half of 2020 // Official website of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation (http://cdep.ru/index.php?id=79&item=5460).

[11] Prior to 2018, convictions for statements were divided into “inappropriate” and “all other.”

[12] Rabat Plan of Action on the prohibition of advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence // SOVA Center. 2014. 7 November (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2014/11/d30593/).

[13] Mikhail Shendakov refers to himself as an officer of the USSR and to the Russian Federation as a criminal corporation. In his speeches, he regularly calls out "Putin's giant squid.” He has repeatedly participated in the "Russian Marches" in Moscow (in 2017-2019) and has previously been repeatedly prosecuted for both criminal and administrative offenses.

[14] All further numbers reflect the convictions known to us, although, judging from the Supreme Court data, the actual numbers are about twice as high. But given the volume of available data, it can be assumed that the observed patterns and proportions will hold true for the total number of verdicts.

[15] About her and other "citizens of the USSR" see: Akhmetyev Mikhail, Citizens without the USSR. Communities of "Soviet citizens" in modern Russia. Moscow: SOVA Center, 2021.

[16] Later, the Second Court of Cassation commuted the sentence, replacing the general regime colony with a settlement colony (the least strict penal colony).

[17] Natalia Yudina. Anti-extremism in Quarantine // SOVA Center. 2020. 4 March (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2021/03/d43757/).

[18] Very likely mostly on VKontakte.

[19] Not including the obviously unlawful ones.

[20] See: for example: Natalia Yudina, Anti-Extremism in Virtual Russia in 2014-2015 // SOVA Center. 2016. 29 June (http://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2016/06/d34913/).

[21] Yudina, Anti-extremism in Quarantine.

[22] Natalia Yudina. In the Absence of the Familiar Article. The State Against the Incitement of Hatred and the Political Participation of Nationalists in Russia in 2019 // SOVA Center. 2020. 27 February (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2020/02/d42132/).

[23] In one case, graffiti was painted on a fence, in another – on the wall of a church.

[24] See: Cases of terrorist propaganda in pre-trial detention centers and places of detention // SOVA Center. 2019. 15 April (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/persecution/2019/04/d40881/).

[25] Although their descriptions are, regrettably, not always accurate.

[26] See: Kravchenko, Inappropriate Enforcement of Anti-Extremism Legislation in Russia in 2021.

[27] In the first half of 2021, 57 people were convicted under Article 2822 of the CC, for 54 of them this was the main charge. Three were convicted under Article 2821, 35 people under Article 2055, and 17 – under Article 2054.

[28] The sentences are also taken into account in the calculation of sentences for hate crimes. See: Yudina, The State Has Taken up Racist Violence Again.

[29] Earlier, Yuri Lunin had already been convicted under Part 4 of Article 111 of the Criminal Code (intentional infliction of serious, life-threatening harm to health, resulting in death by negligence of the victim) and sentenced to six years in prison; in 2015, he was released on parole.

[30] At least three other people were involved in the case, but the cases against them were terminated "due to active repentance" and "reconciliation of the parties," after payment of material compensation to the victims.

[31] However, Metlin was released from paying a fine due to the time he spent in jail during the investigation.

[32] For more see: Akhmetyev, Citizens without the USSR. Communities of “Soviet citizens” in modern Russia.

[33] On Spiritual-Ancestral Empire Rus see, for example: In Krasnodar Krai, a verdict was passed in the case against members of the Spiritual-Ancestral Empire Rus // SOVA Center. 2017. 27 December (http://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2017/12/d38580/).

[34] Memorial Human Rights Center usually recognizes those convicted in the cases related to At-Takfir Wal-Hijra as political prisoners, as it sees neither the evidence of their involvement in this organization, nor that of its very existence. See, for example: Dagestan: extremism charges for talking about religion? // Memorial Human Rights Center. 2020. 22 August (https://memohrc.org/ru/special-projects/dagestan-obvinenie-v-ekstremizme-za-besedy-na-religioznye-temy).

The appropriateness of the verdict on anti-extremism articles in these last cases seems questionable to us, but we cannot make any definite judgment on these cases.

[35] The A.U.E. movement is recognized as extremist// SOVA Center. 2020. 17 August (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/persecution/2020/08/d42774/)

[36] Sergei Finagin, detained together with Yekishev and Antonov, was sent by the 2nd Western District Military Court to compulsory treatment on April 28, 2021.

[37] Court recognizes NOMP as a terrorist organization // SOVA Center. 2015. 18 February (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2015/02/d31308/).

[38] As of February 19, 2022, the list has 5259 entries.

[39] See: Kravchenko, Inappropriate Enforcement of Anti-Extremism Legislation in Russia in 2021.

[40] For more see: The Nation and Freedom Committee is recognized as extremist // SOVA Center. 2021. 29 July (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2020/07/d42712/).

[41] Including for the attack on Egyptian nationals in 2018 and the attack on anti-fascists in July 2018.

[42] In 2015, the group leader was convicted under Article 111 of the Criminal Code (intentional infliction of serious harm to health). From 2015 to 2020, he committed three offenses of posting extremist materials on the Internet (Article 20.29 of the Administrative Code) and public display of Nazi symbols (Article 20.3 of the Administrative Code). 12 other members of the group were prosecuted under the same articles of the Administrative Code. One of them also received a 1.5-year suspended sentence under Article 115 of the CC (intentional infliction of minor injury to health) for attacking natives of the Caucasus. Four other participants of Irtysh Ultras in 2015 and 2018 were convicted under Article 282 of the Criminal Code.

[43] Budnikov was previously convicted on October 3, 2008 for distributing anti-Semitic and extremist publications under Part 1 of Article 280 and received a 2-year suspended sentence with a probation period of two years. Since the mid-2010s, he has been living in Ukraine.

[44] For more see: Akhmetyev, Citizens without the USSR. Communities of “Soviet citizens” in modern Russia.

[45] The court of cassation upholds the decision to recognize Falun Dafa as an extremist organization // SOVA Center. 2021. 12 July (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/persecution/2021/07/d44548/).

[46] Court of Appeal upholds ban on FBK, FZPG, and Navalny Headquarters // SOVA Center. 2021. 5 August (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/persecution/2021/08/d44675/).

[47] Not counting 395 local organizations of Jehovah's Witnesses, banned together with their Management Center and listed under the same entry.

[48] The Nevograd group is recognized as extremist // SOVA Center. 2021. 21 October (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2021/10/d45172/).

[49] About him, see: Yudina, The State Has Taken up Racist Violence Again.

[50] The verdict in the case of three supporters of Artpodgotovka comes into force // SOVA Center. 2021. 7 July (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2021/06/d44892/).

[51] A non-existent organization of Satanists has been recognized as extremist // SOVA Center. 2011. 4 February (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/persecution/2011/02/d20924/).

[52] For more see: Kravchenko, Inappropriate Enforcement of Anti-Extremism Legislation in Russia in 2021.

[53] Consolidated statistics on the activity of federal courts of general jurisdiction and magistrate courts for the first half of 2020.

[54] One of the attackers, G. Shtykina, was also sentenced to community service under Article 116 of the Criminal Code (beatings motivated by national hatred). The two girls from Buryatia, Saryuna Rinchinova and Irina Darnaeva, were attacked in one of the courtyards on Yan Rainis Boulevard in Moscow. One of the victims posted a video about the incident on Instagram; the video received a wide public response, and the Plenipotentiary representative of the Republic of Buryatia in Moscow intervened.