Summary

Systematic Racist and Neo-Nazi Violence : Attacks Against “Ethnic Outsiders” : Attacks Against Ideological Opponents : Attacks Against the LGBT : Other Attacks

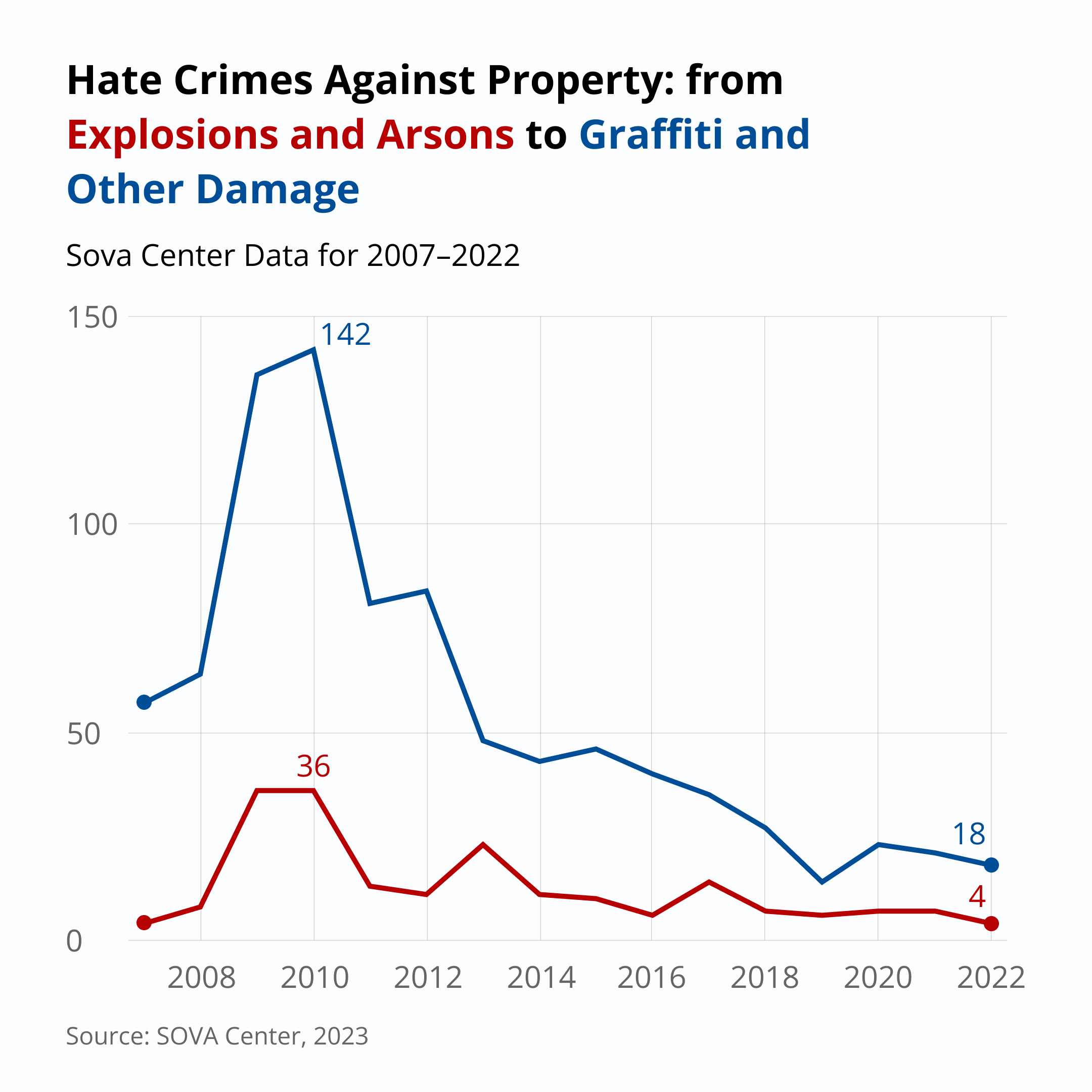

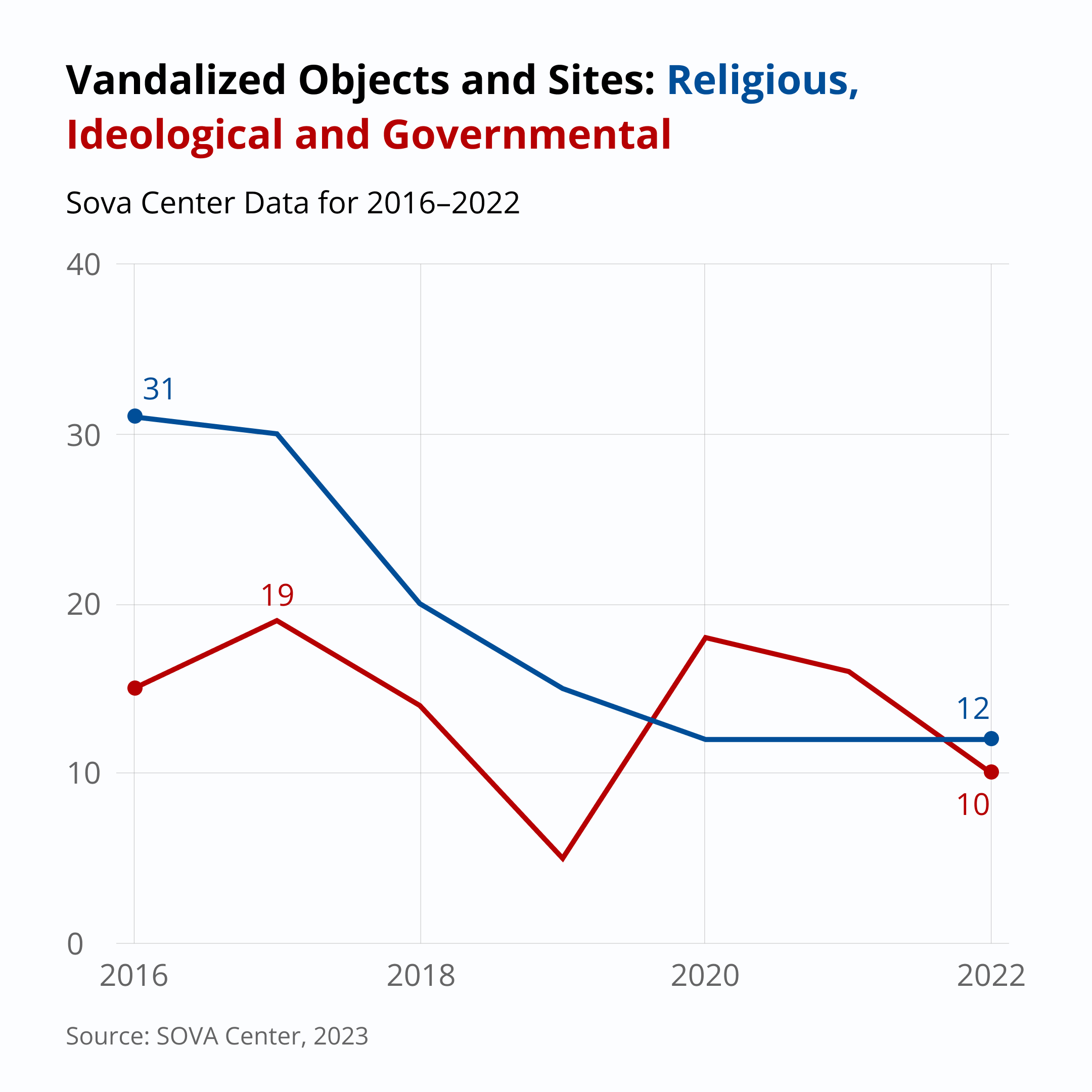

Crimes Against Property

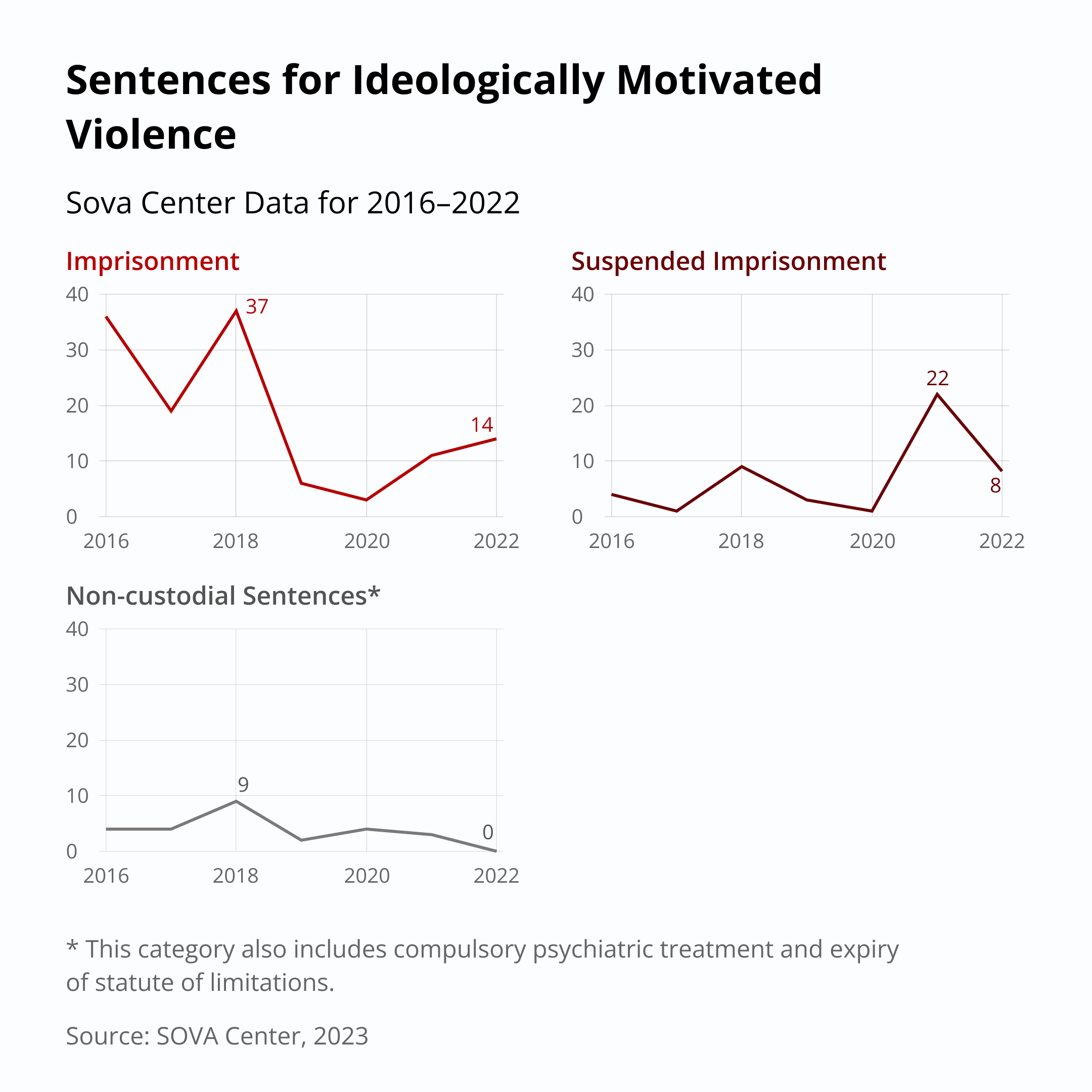

Criminal Prosecution for Violence

Criminal Prosecution for Crimes Against Property

This report by SOVA Center[1] focuses on the phenomenon of hate crimes, that is, criminal offenses that were committed on the grounds of ethnic, religious, or similar hostility or prejudice[2], and on the state’s countermeasures to such crimes.

Summary

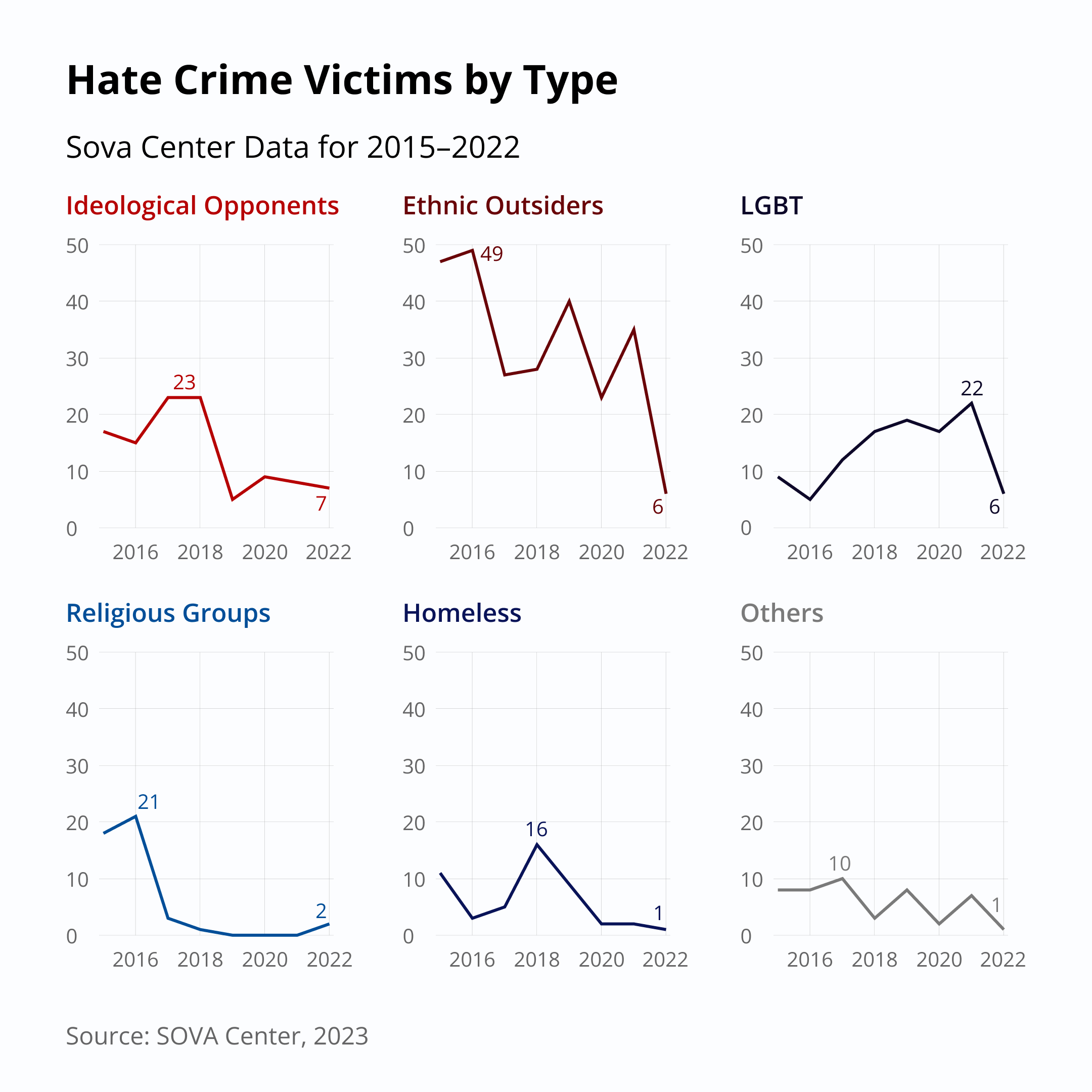

According to our incomplete data, the number of xenophobically motivated attacks decreased radically during the past year. This decrease was primarily due to the drop in the number of the targets perceived by the attackers as “ethnic outsiders”. The reason for such a dramatic drop in xenophobic crime is not entirely clear. Perhaps it is a more consistent silencing of this kind of data by law enforcement agencies and the media, or it could also be that since February, many militant far-right activists have shifted their attention to the events in Ukraine, and some of them have simply left the country, including to fight at the front.

Despite the rhetoric being cultivated by the state of fighting for “traditional values”, the number of attacks against LGBT people has also decreased noticeably. The reason probably lies also in the emigration of both many prominent LGBT activists and some of the anti-LGBT activists. However, homophobic sentiments in the Russian society are very strong; most of the victims suffered homophobic attacks only because they looked like LGBT people: an earring, long hair, etc. served as the reason for the beating.

The number of attacks on "ideological opponents" of the ultra-right also decreased during the year, but not so radically.

2022 saw slightly fewer cases of damage to buildings, monuments, cemeteries, and various cultural sites motivated by religious, ethnic, or other xenophobic hatred than the previous year; the number of attacks on religious sites remained the same. The share of dangerous acts such as explosions and arson also decreased this year.

The number of convictions for hate-motivated violence has also declined. In 2022, two formerly well-known neo-Nazis were finally convicted in the murder case, the subject of the viral video titled Execution of a Tajik and a Dagh. Apart from that, 2022 saw the names of organizations that date back to the early 2000s resurfaced in criminal reports. Preparations are underway for the trials of former members of the Borovikov-Voyevodin gang for murders committed 20 years ago and of a group of members of the banned organization NS/WP, suspected of planning political murders in more recent years. We also know about the convictions handed down to members of new groups - White City 31 in Belgorod, the Astrakhan National Movement (ANM), and Belaya Ukhta in Komi.

Overall, the analysis of the data on hate crimes and countermeasures to such crimes gives the impression of a certain lull in this area.

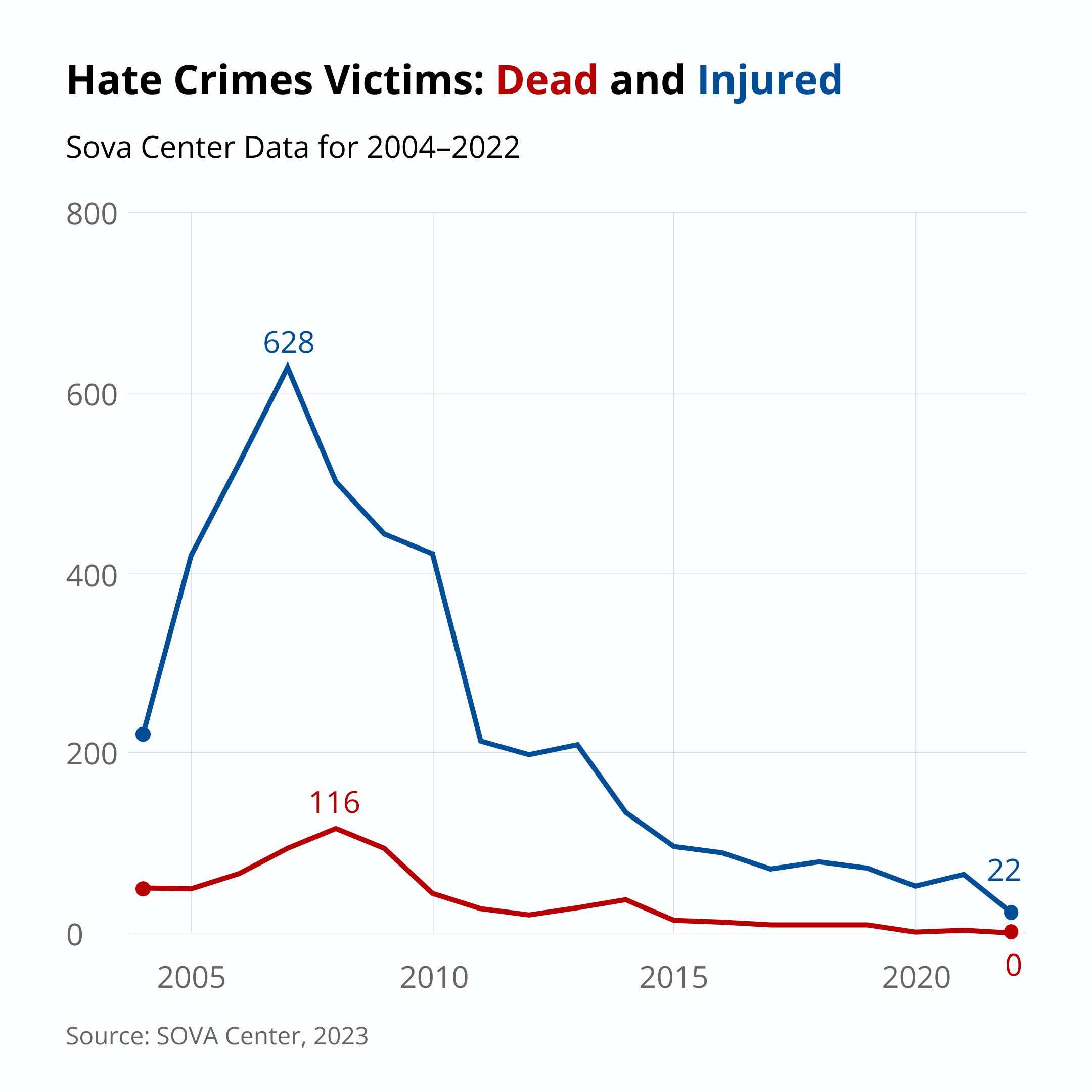

Systematic Racist and Neo-Nazi Violence

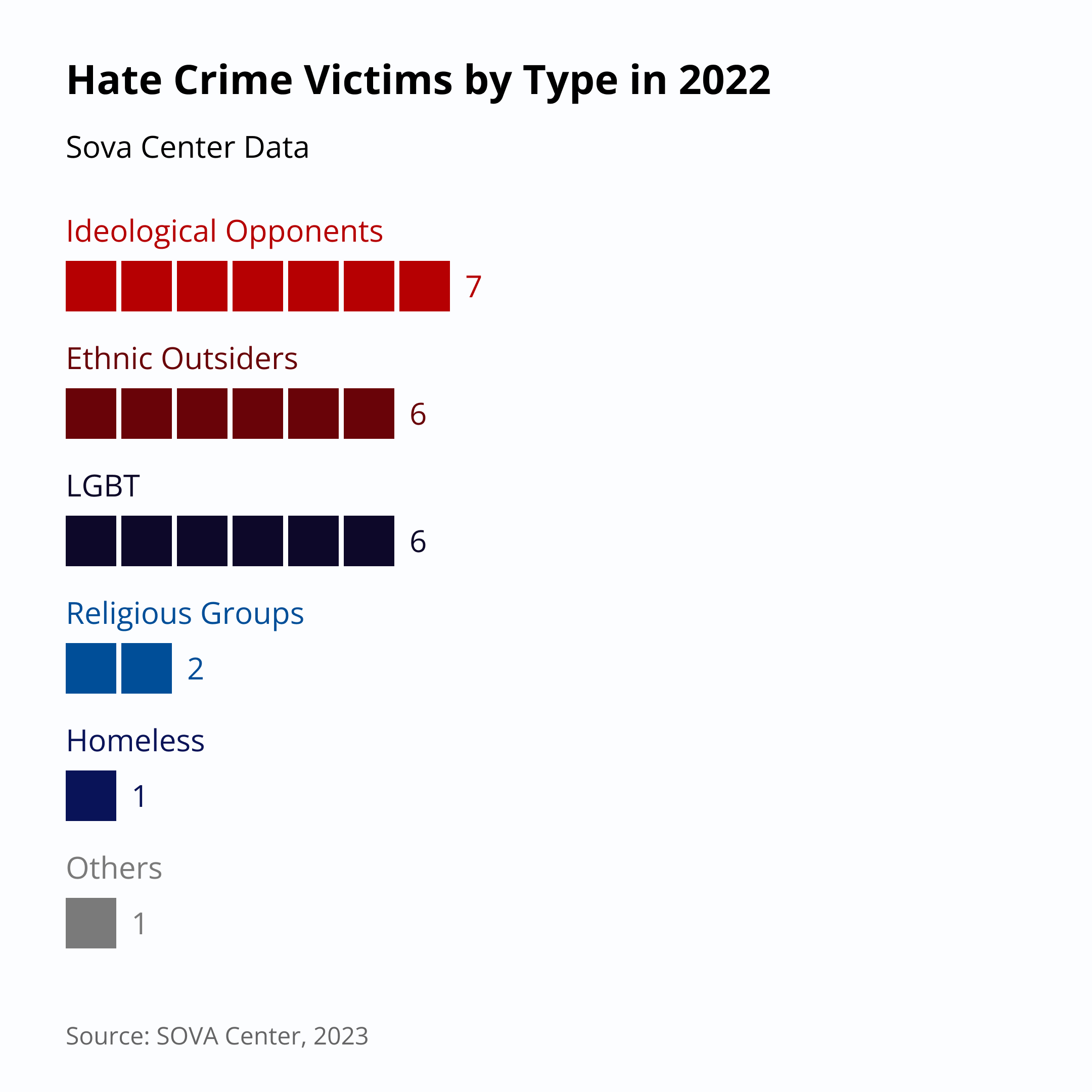

According to the Sova Center monitoring data, 22 people suffered from ideologically motivated violence in 2022. In addition, one person received a serious death threat. Thus, we record a significant decrease in the number of ideologically motivated serious attacks in our statistics: in 2021, we have information on 68 victims and six death threats[3]. Of course, the data for the past year are not final, as we learn about some attacks with delay[4]. Thus, in November 2022 alone, we learned from a sentencing report that members of the neo-Nazi group White City 31 had committed more than 30 racist attacks on migrants between the year 2019 and June 2021. However, in the absence of any additional information, we were unable to account for these 30 episodes in our statistics.

Our methodology is not universal. It does not work for the republics of the North Caucasus, so we do not include data from that area[5]. Relatively little is known about incidents between different minority groups motivated by ethnic hatred. In addition, our data on hate crimes in Russia cannot be compared with any other statistics, since no other open statistics exist.

We are not aware of the true extent of racist violence in the country, but since we have hardly changed the methodology since the beginning of our records, we are able, to some extent, to estimate the dynamics and major trends[6].

We have repeatedly written about the difficulties associated with collecting information about these kinds of incidents[7]. In addition to everything we have been noting earlier (the lack of information and adequate description of incidents in the media, the reluctance of victims to turn to law enforcement or human rights organizations, the precautions the attackers take when posting videos of attacks, etc.), 2022 has added new reasons related to the military operation in Ukraine and Russia’s growing political repressions. As in 2014[8], the attention of ultranationalists was drawn to the events in Ukraine, and some of the militant far-right went directly to the places of military action[9], although this form of activism did not reach the level of 2014. Some nationalist activists simply left the country, including to escape the draft.

In the past year, we recorded attacks in eight regions of the country (in 2021 - in 18 regions). Moscow and St. Petersburg traditionally lead in terms of the level of violence, but they do so in the unusual order: seven victims in St. Petersburg and five in Moscow. Next come the Moscow and the Chelyabinsk regions and the Crimea (two victims in each).

Attacks Against “Ethnic Outsiders”

In 2022, we recorded six ethnically motivated attacks, that is, attacks on those whom the attackers perceived as ethnic outsiders. The decline in violence is particularly noticeable in this category. In 2021, 35 ethnically motivated attacks were recorded (23 in 2020, and 40 in 2019).

Victims in this category include natives of Central Asia, Yakuts, and people of color.

The events in Ukraine and the massive anti-American and anti-Western propaganda in the media have added new overtones to such attacks. It is quite telling that the attackers of one of the black victims in St. Petersburg were shouting anti-American slogans and phrases like "People like you are killing our soldiers.” The racist nature of the attack was corroborated by the fact that the beating continued even after the victim shouted that he was "from Africa”[10].

Less radical forms of racism toward people of color have not disappeared either in 2022. A June incident during a bus ride in St. Petersburg involving a dark-skinned model, Stella Kaziyake, gained media notoriety: a man sat down next to her and started bullying and xenophobically insulting her, while preventing her from getting off the bus. Fortunately, there was no physical violence, and another passenger interceded for the girl[11]. And xenophobic insults in sports (especially against people of color) have long stopped surprising anyone. In the past year in Kaliningrad, during one of the timeouts in the Lokomotiv-Uralochka volleyball match, coach Andrey Voronkov made a racist remark about the Cuban player Ailama Montalvo.

In addition to individual attacks in the streets and in public transport, in 2022 we reported one case of a mass brawl between local youths and natives of the Caucasus in the city of Kovdor in Murmansk Oblast on the night of July 4. After a domestic conflict in a cafe near the local shopping center there was a mass brawl involving between 20 and 30 people. After that, large groups of local youths began gathering in the city and chanting xenophobic slogans, and phrases such as "Devils", "You shall not live", "Rats, run", "88", etc. were spray-painted on businesses owned by migrants. Fortunately, order was restored when reinforced squads of police, Rosgvardia, and traffic police arrived[12].

Manifestations of xenophobic aggression are certainly unacceptable in any form, but especially frightening are the cases involving people of authority and government institutions staff, such as the employee of the Voronezh Migration Center, who attacked a visitor from Uzbekistan in July 2022[13]. The incident drew attention after the head of the Uzbek diaspora informed the Prosecutor's office about it.

Unfortunately, Russian society’s routine xenophobia is not disappearing, and we regularly encounter its manifestations. For example, in Yekaterinburg, two Tuvan women with Russian passports were not allowed into the Air club because of "their appearance and ethnicity”. On similar grounds, dark-skinned young men were later denied entry into the same venue.

Attacks Against Ideological Opponents

Unlike the previous category of victims, the number of attacks by the ultra-right against their political, ideological, or “stylistic” opponents in 2022 – seven beaten – was nearly the same as in the previous year (eight in 2021, and nine in 2020)[14]. As a result, this category of victims is dominant in our statistics. Among the victims were both non-ideological, non-political non-conformists and ideological opponents (anti-fascists), mostly patrons of the San-Galli Garden on Ligovsky Prospect in St. Petersburg, popular among the city's non-conformist youth because of its proximity to the ETAGI loft space.

Alexei Venediktov, the former editor-in-chief of Ekho Moskvy radio, faced both political hatred and anti-Semitism at the same time: on March 24, a pig’s head with a curly wig and a sticker with the Ukrainian coat of arms and the sticker saying “Judensau” ("Jewish pig") were placed outside his Moscow apartment door[15].

Attacks Against the LGBT

The number of attacks against the LGBT community went down compared to the previous year. SOVA Center has recorded six victims (22 beaten in 2021, 17 in 2020). The reason for this decrease is probably the fact that LGBT activists have not held any actions in the past year, and many of those associated with LGBT activism in one way or another have simply left the country after the start of hostilities in Ukraine. One of the most active organizers of LGBT harassment, the leader of Male State Vladislav Pozdnyakov, has also left the country.

However, homophobic sentiments in Russia have not disappeared, and this is evidenced by the fact that most of the victims in the past year have been beaten and insulted with homophobic slurs simply because they looked like LGBT.

Ultra-right Occupy Pedophiliay actions in the spirit of the late Maxim (Tesak) Martsinkevich have also been held[16]. In November, a video of a man being beaten appeared in one of the ultra-right Telegram channels. The creators of the video, posing as a minor, started correspondence with a native of Uzbekistan, lured him to a meeting, threw him on the ground, and beat him.

Members of the ultra-right Russia Conservative movement harassed drag queen Sergey Nechaev, known under a stage name of Bomba Kibersisi (Cybertits), and forced him to apologize on camera for "insulting Russia and the Russian people." On August 7, Nechaev performed at the Fame club in Yekaterinburg to the Russian anthem sung by Larisa Dolina; nationalists were particularly inflamed about the rainbow flag the artist was holding.[17]

Other Attacks

In 2022, we have no information on any attacks against homeless people. We know only about the planning of such a murder in Moscow by members of the Maniacs. Cult of Murder (M.K.U.) group, recently recognized in Russia as a terrorist organization[18]. Three teenagers were planning to kill homeless people in a wooded area near Kosino railway station, but were detained by law enforcement officers.

A video from Novorossiysk, circulating in the right-wing segment of the Internet, shows a group of young men violently beating people, throwing rocks at them, and spraying the contents of spray cans in their faces. The caption under the video states that a "hunt has been declared” for drunk people in the city's Yuzhny district, in the spirit of the Nazi Straight Edge subculture, which promotes a healthy lifestyle and calls for "cleansing the country" of "biowaste”.

Crimes Against Property

Crimes against property include damage to cemeteries, monuments, various cultural sites, and property in general. They are categorized under several different articles of the Criminal Code, but the enforcement is not always consistent. Such acts are usually referred to as vandalism, but we rejected this term a few years ago, as the term “vandalism,” be it in the Criminal Code or everyday language, clearly does not encompass all possible types of damage to property.

In 2022, the number of religious, ethnic, or ideological hate crimes against property continued to gradually decrease: we have information about 22 incidents in 14 regions (28 in 2021, and 30 in 2020). Our statistics does not include isolated cases of neo-Nazi graffiti and drawings on buildings and fences, but it does include serial graffiti (though law enforcement considers graffiti to be either a form of vandalism or a means of public statement).

In 2022, 10 sites were targeted due to ideological, and not religious, reasons, which is higher than the 16 ideological, including one government, sites targeted in 2021. Among these sites are monuments to Lenin and heroes of the Great Patriotic War. Of special note is setting fire to a hookah lounge in Shakhty, the Rostov region: the video of the arson was published online with “an inscription inciting ethnic strife”.

Our statistics does not include a 19 January 2022 neo-Nazi act at the site of a temporary memorial to Stanislav Markelov and Anastasia Baburova, murdered on that day in 2009: Insulting slogans were written on the photos, and portraits of the former members of the neo-Nazi Combat Organization of Russian Nationalists (BORN) Nikita Tikhonov and Yevgenia Khasis, convicted for the murder in May 2011, were placed at the memorial.

Religious sites traditionally represent a significant share of the targets. The total number of attacks in 2022 was the same as the year before (12 religious sites in both 2022 and 2021), and, unlike the previous year, exceeded the number of attacks on ideological sites. Orthodox churches and crosses, with five incidents (four in 2021), and various Jewish sites, with five incidents (three in 2021) became the most frequent target. Muslim and Buddhist sites had one incident each (none in the year before). Neo-pagan sites were not affected (compared with four in 2021).

The share of the most dangerous acts – arson and explosions – also decreased compared to the previous year (four arsons), and the share of such acts was 18%, or four out of 22 (seven out of 28, or 25%, in 2021).

As in 2021, the regional distribution has changed noticeably. In 2022, this type of crime was reported in 11 new regions (12 in 2021): Kaliningrad, Moscow, Nizhny Novgorod, Novosibirsk, Smolensk, Tver, and Tomsk regions, Perm Krai, the Republics of Altai, Tatarstan, and Khakassia. On the other hand, 15 regions where such crimes have been reported in 2021 went off the list (14 in 2021): St. Petersburg, Amur, Volgograd, Kaluga, Murmansk, Novgorod, Omsk, Orenburg, Samara and Yaroslavl regions, Primorsky Krai, the Republics of Buryatia and Komi, Yakutia, and Crimea.

Again, for the fourth consecutive year, the geographical spread of the xenophobic vandalism (14 regions) turned out to be wider than that of the acts of violence (8 regions).

Both types of crimes were recorded in four regions (nine in 2021, five in 2020–2019): in Moscow, the Moscow and Nizhny Novgorod regions, and Krasnodar Krai.

Criminal Prosecution for Violence

In 2022, the number of those convicted of violent hate crimes known to us was significantly lower than in 2021. In 2022, not less than 10 guilty verdicts where the hate motive was officially recognized by courts were issued in nine regions[19]. 22 suspects were found guilty in these trials (36 in 2021, 8 in 2020). Official statistics on sentences with hate motive are not available, since this qualifying feature does not constitute part of an article of the Criminal Code, but only a paragraph, and the sentencing statistics are published by the Supreme Court by parts of the articles.

Racist violence was categorized under the following articles containing hate motive as a categorizing attribute: Murder (Paragraph L of Part 2, Article 105 of the Criminal Code), Intentional Infliction of Injury to Health of Average Gravity (Paragraph E of Part 2 of Article 112), Hooliganism (Paragraphs B and C of Part 1, Article 213), Threat of Murder (Part 2 of Article 119) – this standard set of articles has been applied in the last few years.

Article 282 of the Criminal Code (incitement of enmity) was applied in one guilty verdict for a violent crime (2 in 2021). In St. Petersburg, several Azerbaijan nationals were convicted of assaulting two Armenians while shouting anti-Armenian slogans and insults (“Armenians must be murdered!”, “Whose is Karabakh, Ara?”, etc.) under Paragraph A of Part 2, Article 282 of the Criminal Code (incitement of enmity with the use of violence). We believe that other articles with the categorizing attribute could have been applied, such as Articles 116, 115, or 112 of the Criminal Code, depending on the severity of the injuries sustained. However, this application of Article 282 is also allowed: the resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation of 28 June 2011 No. 11 “On Judicial Practice in Criminal Cases on Offences of an Extremist Nature”[20] states that Article 282 of the Criminal Code may be applied to violent crimes if they are aimed at inciting hatred or enmity in third parties, such as in the case of a public and demonstrative ideologically motivated attack. In this case, the fact of public demonstration is obvious: the attack was recorded on video and posted online.

Penalties for violent acts were distributed as follows:

- 3 persons sentenced to more than 10 years in prison;

- 4 persons sentenced to up to 10 years in prison;

- 2 persons sentenced to up to 5 years in prison;

- 5 persons sentenced to up to 3 years in prison;

- 8 persons received suspended sentence.

The suspended sentences were given to the underage members of an extremist community in Astrakhan for attacks whose nature is unknown to us and to the leader of the neo-Nazi association Belaya Ukhta for, among other things[21], carrying out, together with others, "direct action" and beating up "people of asocial lifestyles”.

The others convicted in 2022 were sentenced to terms of various lengths, which seem to us to be quite proportionate to their crimes. Among those sentenced to lengthy prison terms were the veterans of the ultra-right movement Sergey Marshakov (Skin Legion, etc.) and Maxim Aristarkhov (Format-18), who got 17 and 16 years in a high-security penal colony in the case of the double murder of Shamil Udamanov (Odamanov) and another, unknown man from Central Asia, recorded in the 2007 viral neo-Nazi video Execution of a Tajik and a Dagh in 2007[22]. The saddest thing is that the neo-Nazis (and not all of them at that) were punished for this murder with a 15-year delay, and the father of the murdered victim, who had identified his son in the video, has not lived to see the first verdict and never found out where his son was buried. However, it seems that law enforcement officials finally got their hands on investigating murders from 15-20 years ago. Two far-right suspects accused of killing an Uzbekistan national in 2007 were recently detained in the Tula region[23]. Both of them have been previously prosecuted in other criminal cases. Three former members of the banned neo-Nazi Combat Terrorist Organization (CTO), also known as the Borovikov-Voyevodin gang, were arrested in St. Petersburg on suspicion of two murders committed in 2003. Along with them, Alexei Voevodin, already serving a life sentence, is also suspected[24].

Other members of neo-Nazi gangs also found themselves behind bars in 2022. For example, in Belgorod, three members of White City 31 received prison sentences for a series of racist attacks on migrants from Syria, China, and other countries in 2019-2020. In Astrakhan, the leader of the Astrakhan National Movement got seven years in prison, including for hate-motivated attacks. The already mentioned juvenile members of the same group received suspended sentences.

Noteworthy is the arrest in April of a group of members of NS/WP (National Socialism/White Power), a neo-Nazi terrorist organization banned in Russia[25], on suspicion of planning, on the instructions of the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU), the "murder of a public figure, the famous journalist Vladimir Solovyov" and discussing the murder of other prominent propagandists (Dmitry Kiselev, Olga Skabeyeva, Margarita Simonian, and Tigran Keosayan). Among those detained were previously convicted neo-Nazis, including Andrei (Bloodman) Pronsky, a veteran of NS/WP often referred to as the leader of the group, and the Oderint, Dum Metuant Telegram channel administrator, known by the nickname of Signature Illegible. Later, in June, a sixth suspect in the case was detained in Moscow. He had been on the run for almost 1,5 months and during that time had organized several arson attacks on military enlistment offices[26].

After reports of the arrests were published, a statement appeared in one of the far-right Telegram channels on behalf of NS/WP confirming the detained individuals’ membership, but denying any connections to the security or special services of Ukraine.

On 20 April, Hitler’s birthday, SOVA Center received an e-mail with the subject line NS/WP WE ARE BACK, in which NS/WP claimed responsibility for arson attacks on vehicles bearing the Z symbol.

Criminal Prosecution for Crimes Against Property

In 2022, we have information about eight sentences for crimes against property, where hate motive was lawfully and appropriately cited; nine suspects were convicted (seven in 2021, one in 2020). In this report, we do not include multiple other convictions whose lawfulness we doubt; the vast majority of the attacks against material objects in question were a form of protest against the military operation in Ukraine, and enforcement of those convictions will be discussed in the report on abusive anti-extremism. In all, in 2022 we know of 21 convictions for crimes against property, qualified as ideologically motivated, against 25 people.

As is the case with violent hate crimes, the statistics of sentences published by the Supreme Court does not allow us to isolate the data we need: in Article 244 of the Criminal Code on cemetery vandalism, the motive of hatred is a paragraph, not part of the article, and in Article 214 of the Criminal Code (Vandalism) it constitutes part of the article together with deeds committed by a group.

Almost all the sentences we are aware of were handed down under Part 2 of Article 214 of the Criminal Code (hate-motivated vandalism). Only two people were charged under this article alone: In Novomoskovsk, the Tula region, two schoolchildren received 10 months of restricted freedom and a year of educational measures for drawing Nazi symbols on the walls of a house and a garage and recording their actions on video, which they then showed to their friends. In the other cases, Article 214 was combined with other articles.

In Astrakhan, the leader of the Astrakhan National Movement was sentenced to prison and two other members of the same organization received suspended sentences. In addition to acts of violence, the organization members sprayed paint onto the monuments to the Tatar poet Gabdulla Tukai, the Nogay enlightener Abdul-Hamid Dzhanibekov, and the poet Makhtumkuli Fraghi.

In Volgograd, Kirill Zaruykin was sentenced to prison for desecrating a monument to Holocaust victims and for attempted robbery of a pawnshop and Bristol liquor store.

In Zabaykalsky Krai, Kirill Sedyakin, a member of the already mentioned M.K.U., received a suspended sentence under a combination of Part 2 of Article 214 and Article 280 of the Criminal Code (public calls to extremist activity) for drawing neo-Nazi symbols and writing phrases "calling for racial and ethnic hatred" on public buildings in Chita and sending out "specially prepared “instructions on how to commit extremist acts" via a messenger.

[1] Our work on this issue is supported by the Norwegian Helsinki Committee and Berta International.

[2] Hate Crime Law: A Practical Guide. Warsaw: OSCE/ODIHR, 2009 (available on the website of the OSCE in several languages, including Russian: http://www.osce.org/odihr/36426).

Verkhovsky Alexander. Criminal Law on Hate Crime, Incitement to Hatred and Hate Speech in OSCE Participating States (2nd edition, revised and expanded). Moscow, 2015 (available on the website of SOVA Center: http://www.sova-center.ru/files/books/cl15-text.pdf).

[3] Data for previous years are provided as of 20 January 2023.

[4] Compare, for example, with the data from the previous report: Yudina N. The State Has Taken Up Racist Violence Again // SOVA Center . 2022. 31 January (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2022/01/d45715/ ).

[5] Neither do we take into account the four regions of Ukraine that have been under Russian jurisdiction since last fall. But we do account Crimea, whose actual regime in recent years has not differed much from the regions of southern Russia.

[6] Here and below, all chart data are based on the monitoring by SOVA Center.

[7] See: Yudina N. The State…

[8] Alperovich V., Yudina N. The calm before the storm? Xenophobia and radical nationalism and counteraction to Them in Russia in 2014 // SOVA Center. 2015. 26 March (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2015/3/d31575/).

[9] Alperovich V. Russian nationalists on the Ukrainian and ideological “fronts”. Public activity of far-right groups, summer and fall 2022 // SOVA Center. 2022. 29 December (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2022/12/d47447/).

[10] Megapolis and Fontanka: Suspects who violently beat a black man while shouting “People like you are killing our soldiers” detained in St. Petersburg // Mediazona. 2022. 1 August (https://zona.media/news/2022/08/01/izbienie).

[11] The offender, Nikita Ustyuzhanin, was later detained and sentenced under Article 20.3.1 (inciting hatred or enmity, as well as disparagement of human dignity) and Part 1 Article 20.1 of the Administrative Code (disorderly conduct) to seven days of arrest and 50 hours of community service. See: Suspect detained in St. Petersburg for xenophobically insulting a woman of color on a bus // SOVA Center. 2022. 16 July (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2022/06/d46448/).

[12] Riots in Kovdor // SOVA Center. 2022. 5 July (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2022/7/d46570/).

[13] A Russian beat up a visitor from Uzbekistan at a migration center and got recorded on video // Lenta.ru. 2022. 7 July (https://lenta.ru/news/2022/07/07/izbilll/).

[14] Attacks of this type peaked in 2007 (7 killed, 118 injured); the numbers have since been steadily declining. After 2013, trends have been unstable.

[15] Anti-Semitic insults targeting the former head of Ekho Moskvy radio Alexei Venediktov // SOVA Center. 2022. 24 March (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2022/03/d46000/).

[16] Nationalist Maksim Martsinkevich dies in pre-trial detention center // SOVA Center. 2020. 16 September (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/2020/09/d42916/).

[17] A fine and a protocol on improper use of the national anthem were issued against Nechaev (Article 17.10 of the Administrative Code). See: Court punishes the Sverdlovsk travesty-patriot Bomba Kibersisi, who sang the Russian anthem while holding an LGBT flag // Ura.news. 2022. 12 September (https://ura.news/news/1052586231).

[18] The Supreme Court recognizes M.K.U. as a terrorist organization // SOVA center. 2023. 16 January (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2023/01/d47493/).

[19] Only the verdicts in which the hate motive was officially recognized and which we consider appropriate are included in this count.

[20] For more on this see: Alperovich V., Verkhovsky A., Yudina N. Between Manezhnaya and Bolotnaya: Xenophobia and Radical Nationalism in Russia, and Efforts to Counteract Them in 2011 // SOVA Center. 2012. 21 February (http://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2012/02/d23739/).

[21] The verdict also cites Article 280 of the Criminal Code (public calls for extremist activity) and Article 354.1 of the Criminal Code (rehabilitation of Nazism).

[22] For more on this case see: Yudina N. Potius sero, quam nunquam: Hate Crimes and Countermeasures in Russia in 2020 // SOVA Center. 2021. 3 February (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2021/2/d43593/).

[23] Suspects detained in the 2007 murder case // SOVA Center. 2022. 12 December (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2022/12/d47342).

[24] Former CTO members are charged with two murders committed 20 years ago // SOVA Center. 2022. 17 November (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2022/11/d47220/).

[25] For more on the ban of NS/WP see: Yudina N. The Well Forgotten Old. Hate Crimes and Countering Xenophobia and Radical Nationalism in Russia in the First Half of 2021 // SOVA Center. 2021. 15 July (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2021/7/d44564/).

[26] Suspects in the plan to assassinate Vladimir Solovyov arrested // SOVA Center. 2022. 25 April (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2022/04/d46180/).