Summary

Systematic Racist and Neo-Nazi Violence : Attacks Against “Ethnic Outsiders” : Attacks Against the LGBT : Attacks Against Ideological Opponents : Other Attacks

Crimes Against Property

Criminal Prosecution for Violence

Criminal Prosecution for Crimes against Property

This report by SOVA Center[1] is focused on the phenomenon of hate crimes, i.e. not on ordinary criminal offenses but those committed on the grounds of ethnic, religious, or similar hostility or prejudice[2] and on the state’s counteraction to such crimes.

Summary

Among other things, the year 2021 was marked by an active anti-migrant campaign.[3] However, if we are to compare it with the memorable anti-migrant campaign of 2013,[4] the current one has led to neither the mobilization of the far-right nor a significant increase in hate crimes, and the overall level of ethnic xenophobia even decreased slightly.[5]

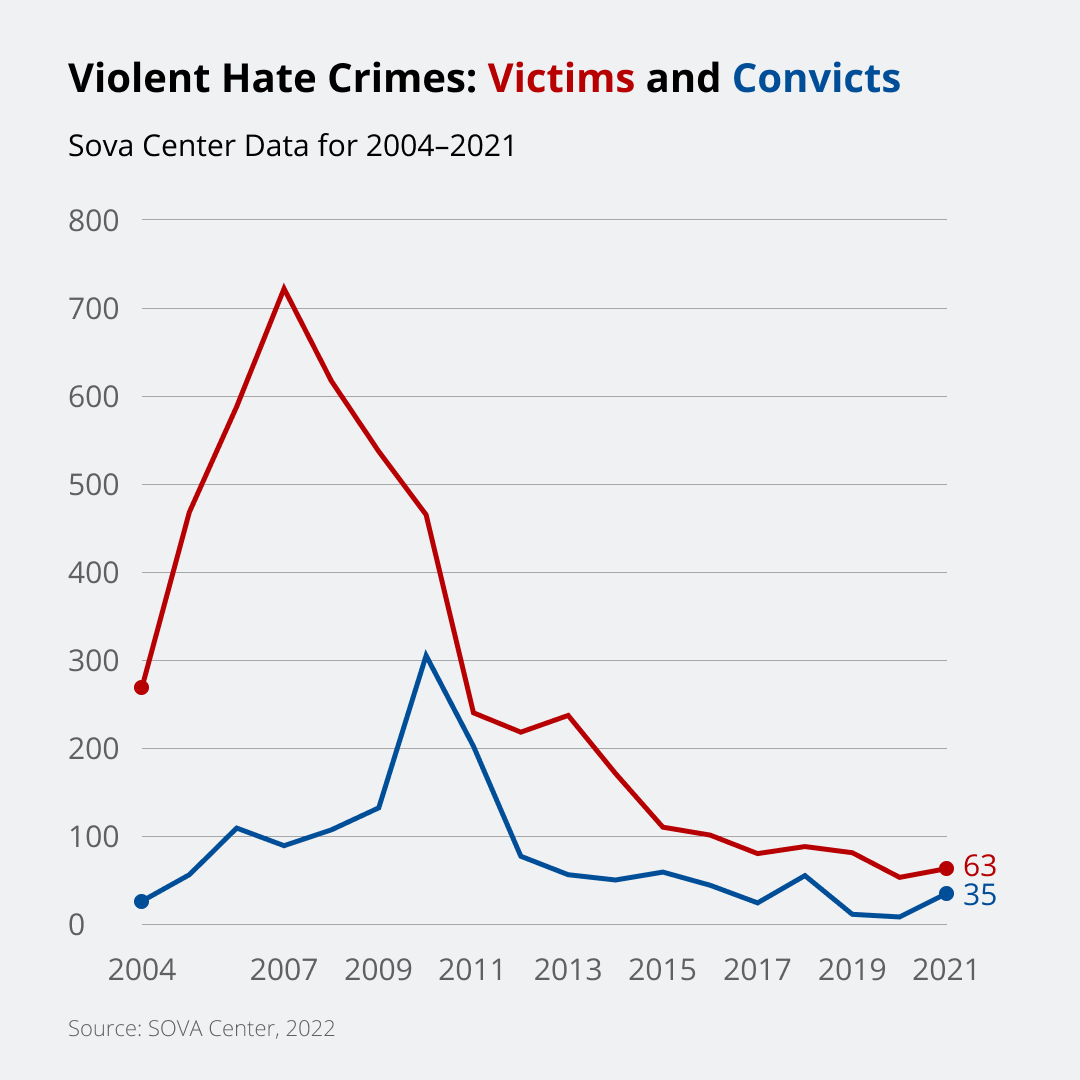

The number of xenophobic attacks known to us has increased somewhat over the past year, both against "ethnic outsiders" and LGBT people and those who were mistaken for such. The nature of some street attacks and clashes resembles the period of activity of Nazi skinheads in the 2000s; anti-pedophile Occupy Pedophilia raids in memory of Maxim (Tesak) Martsinkevich have also intensified. But in general, the level of xenophobic violence remained low.

Ideologically motivated damage to various material objects in 2021 became a little less frequent, but the number of dangerous acts, explosions and arson, has not diminished.

At the same time, the number of convictions for hate crimes skyrocketed fourfold. Perhaps this was due to the fact that several long joint trials have ended at once. At the same time, there are clear signs that new high-profile trials of multiple defendants are being planned: throughout the year, FSB officers reported numerous detentions throughout the country of supporters of the M.K.U gang (“Maniacs. Murder Cult”).

This high activity of law enforcement agencies is probably a response to the emerging, albeit not so significant, rise in hate crimes. Or perhaps the state, which is increasingly invoking the nationalist agenda, is less and less willing to tolerate competition from below, especially militant one.

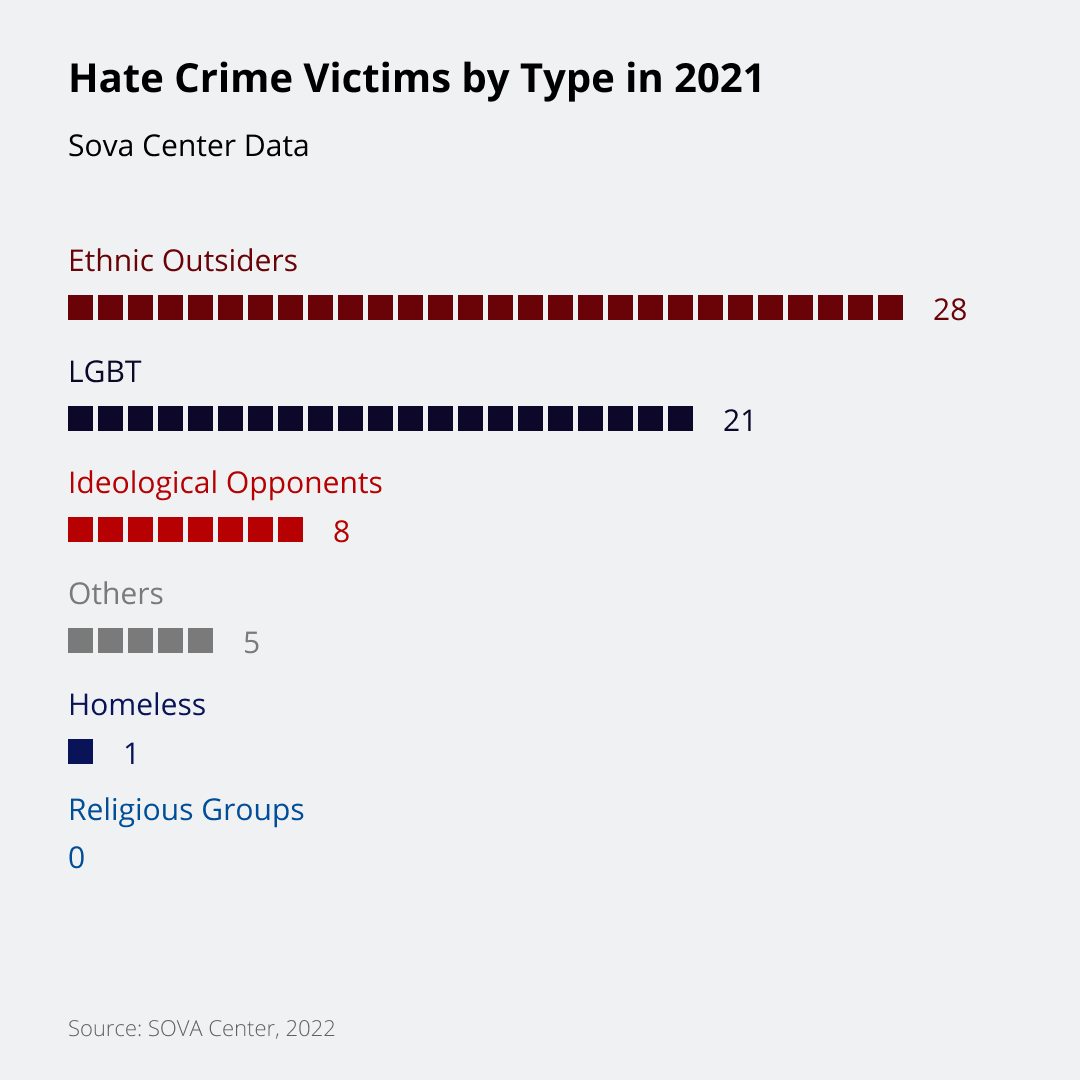

Systematic Racist and Neo-Nazi Violence

In 2021, at least 63 people became victims of ideologically motivated violence; three of them died and the others were injured or beaten; five people received serious death threats. We have to say that the total number of hate-motivated attacks has increased compared to the previous year: in 2020, one victim died and 52 were injured or beaten.[6] And what should be kept in mind is that our data, especially for the year that just ended, is incomplete and will inevitably increase.[7]

We do not report on the victims in the republics of the North Caucasus, where our methods are, regrettably, not applicable. Unfortunately, we cannot compare our data with any other statistics on hate crimes in Russia, as no other statistics exist.

And once again we have to admit that the figures we provide do not reflect the true scale of violence and are incomplete to a significant extent. The lion's share of information about such crimes is provided by the mass media, but in recent years they have reported practically nothing about hate crimes or have described them in such a way that isolating a motive becomes difficult.

Victims themselves hardly ever report the attacks to human rights organizations, except in the hope of receiving legal, medical, educational, or financial assistance. Neither do the victims go to the police, since they do not really expect to get any help from police officers but instead are very much afraid of potential problems.

The attackers have become more cautious and practically never post videos of their “acts.” And when such videos do appear, it is often not possible to verify their authenticity and establish the time and place of the attack.

For example, in the second half of the year, messages containing links to videos and signed by the M.K.U. group were sent to the e-mail address of the SOVA Center several times: videos contained scenes of attacks on migrants and homeless people, arson, messages about upcoming terrorist attacks with addresses (fortunately, the attacks did not take place), and threats against the employees. Based on some of the videos, it is possible to establish that at least five victims were injured, two of whom may have been killed. However, it is impossible to understand where and when these attacks occurred and whether they occurred at all.

As a result, it is difficult to assess what is happening regarding violence, but since our methodology has not changed since the start of the data collection, we are able to analyze the dynamics.[8]

In the past year, we have recorded attacks in 18 regions (in 14 in 2020). Moscow (13 injured and beaten) and St. Petersburg (six injured and beaten) traditionally lead in terms of the level of violence. A significant number of victims was reported in the Novosibirsk, Tver, and Tula regions (four injured and beaten in each). On the contrary, in the Sverdlovsk region, which for two years straight was among the leaders in our sad statistics, the number of victims has decreased (we only know about one).

In the past year, assaults were reported in the regions where they have not been reported before, namely, in the Belgorod, Leningrad, Moscow, Nizhny Novgorod, and Yaroslavl regions, Primorsky Krai, Krasnoyarsk Krai, and Khabarovsk Krai. At the same time, however, a number of regions disappeared from our statistics: hate crimes were not recorded in the Arkhangelsk, Bryansk, Volgograd, Voronezh, Kursk regions, Stavropol Krai, and Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug.

According to our data, in the past ten years, in addition to Moscow, St. Petersburg, and the Moscow and Leningrad regions, crimes have been recorded practically annually in the Volgograd, Vologda, Voronezh, Kaluga, Kirov, Nizhny Novgorod, Novosibirsk, Omsk, Samara, Sverdlovsk, Rostov, and Tula regions, Primorsky Krai, Krasnodar Krai, Khabarovsk Krai, and the Republic of Tatarstan. Additionally, over the past five years, criminal activity in the Kaliningrad, and Orenburg regions, Perm Krai, Zabaykalsky Krai, and the Republic of Karelia has intensified.

However, it is also possible that the incident reporting is just better organized in these regions.

Attacks Against “Ethnic Outsiders”

Those perceived as “ethnic outsiders” remain the largest group of victims. Their numbers are slightly higher compared to the previous year: in 2021, we recorded 28 ethnically motivated attacks, 23 in 2020, and 40 in 2019.

Victims in this category include natives of Central Asia (one killed, three beaten compared to four beaten in 2020) and the Caucasus (three beaten compared to one killed, eight beaten in 2020); individuals of unidentified “non-Slavic appearance” (2 killed 13 beaten compared to 6 beaten in 2020). In 2021, we are aware of other attacks on ethnic grounds, including on one Jew and one Russian. An attack and xenophobic insults against two women from Buryatia received media coverage after one of the victims posted a video of the incident on Instagram on April 14.

Some attacks were marked by outrageous brutality. For example, in June, a citizen of Uzbekistan was attacked in the Leningrad region: the attackers cut off his ear, doused him with gasoline, and set him on fire. In the Moscow metro, two migrants were beaten with bats by a group of aggressive young men in the somewhat forgotten tradition of Nazi skinhead attacks of the early 2000s.

The number of incidents of xenophobic street violence against black people has been growing for the third straight year. In 2021, we have information about five victims (two beaten a year earlier, and one beaten per year in 2017-2019). The level of intolerance towards black people was made obvious by the hate campaign against Natalia Eluemunor, the widow of a Nigerian student who drowned while rescuing a drowning woman: Natalia received racist insults in response to a farewell post on Instagram. The number of xenophobic threats and attacks has increased greatly after the Telegram channel of the founder of Male State Vladislav Pozdnyakov published a link to her page. Eluemunor told reporters that it was not the first time she had to face the manifestations of racism in Russia. “We didn't like walking around the city, because many people reacted very aggressively…” she said. she said.[9] In addition to persecuting individuals, Male State also organized harassment campaigns against businesses for featuring black men in their ads.[10]

The war in Nagorno-Karabakh spilled over into in Russia.[11] In November 2021, news appeared about the conflicts between the natives of Armenia and Azerbaijan in Moscow. On November 16, a native of Armenia living in Moscow live streamed in TikTok negative comments about the natives of Azerbaijan. He was found, beaten, and forced to apologize on camera. On November 27, a video appeared with the apologies of another native of Armenia, who was found and beaten by natives of Azerbaijan. After that, groups of Armenian youth began to hunt around for the offenders. The Azerbaijani Telegram channels also announced the recruitment of “Azerbaijanis from Moscow and the Moscow Region over 18+, self-confident men able to fight and ready to defend the honor of their nation at any moment.”[12]

In February, Azerbaijani natives beat a visitor from Dagestan and forced him to apologize on camera for supporting the Armenians in the war in Nagorno-Karabakh.

Attacks Against the LGBT

The number of attacks against the LGBT community was higher than in the previous year. SOVA Center has recorded 21 victims of beatings (compared to 17 in 2020). We have written more than once about the reasons for the increase in the number of attacks on LGBT people in recent years.[13]

Anti-pedophile raids following the death of a well-known neo-Nazi, the former leader of the far-right Restrukt movement and the founder of the Occupy Pedophilia movement Maxim (Tesak) Martsinkevich[14] have been going on for the second straight year. These raids took place in Vyborg, Leningrad region, in February, in Tver in February and March, in Perm in March, and in Tyumen in December. Tesak supporters contacted men online and lured them to dates, where they were humiliated, kicked, their faces beaten, passport pages with their names shown on camera, and in one case, the page with the registered address; they were forced to say their names on camera, shout "Occupy!", kneel, and apologize.

In 2021, we recorded attacks against individuals connected in one way or another with LGBT activity (for example, those handing out LGBT-themed leaflets and visitors to cafes popular among LGBT people) and locally known LGBT activists (for example, the attack on Yaroslav Sirotkin and Alexander Derek in Yaroslavl, both of whom suffered severe burns to eyes). Attacks against those who were mistaken for LGBT also took place. For example, on August 7 and 29 in Novosibirsk at the Royal Park shopping mall, a group of teenagers with sticks attacked anime fans, shouting homophobic insults. As a result, several people were severely injured. In Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Krasnoyarsk, earrings and dyed hair were enough to provoke attacks and accusations of non-traditional sexual orientation against the young men.

LGBT supporters have received quite serious threats. “TikToker” Leo Velez, who is openly gay, filed a report with the police after his personal data had appeared in a homophobic Telegram channel and he had begun receiving calls from unknown numbers and messages with threats, insults, and blackmail. The Radio Liberty correspondent and author of the telegram channel FemVremya Karina Merkurieva received a series of threats and demands for public apologies from three different Telegram communities for her “LGBT propaganda and insults against men.” And once again, Male State was the most ardent harassment organizer: its activists are responsible for threats against activist Daria Serenko and the reporters for TV Rain (Dozhd) Anna Mongait, Maria Borzunova, and Anna Fimina for publishing an interview with the same-sex couple that had appeared on the cover of Elle magazine.[15]

Attacks Against Ideological Opponents

In 2021, the number of attacks by the ultra-right against their political, ideological, or “stylistic” opponents – eight beaten – decreased slightly compared to the nine beaten in 2020 and five in 2019.[16] Among the beaten were anti-fascists from St. Petersburg and a socialist from the Tula region. Vlad Tupikin, the editor of Volya magazine, also became a victim of an attack: on March 27 in Moscow, an unknown person ran up to Tupikin, who was heading to the presentation of the almanac Moloko+, and hit him in the face, shouting, “Don’t you talk about neo-Nazis here!”

The violent clash between the far-right and antifa before the start of the ultra-right Asgardsrei festival in Moscow brings back memories of the street wars of the early 2000s. The far-right, carrying flags with Nazi symbols, attacked anti-fascists before the concert organized by the White Nights Skins group. Judging by the video, traumatic guns were used. The day after the fight, Sergei Nelyudov, a supporter of the Popular Resistance Association (ANS), and Andrei (Bloodma) Pronsky, convicted in 2013 of xenophobic murder, were among the far-right detainees. (One of the above-mentioned videos sent to SOVA Center by the M.K.U. included footage from the old NS/WP Nevograd video “The Destruction of the Little Jew,” made by Pronsky.)

As is customary, attacks by pro-government groups on liberal opponents have been active throughout the year. SouthEast Radical Block (SERB) was most radical. On April 9, several SERB activists attacked director Vitaly Mansky. Earlier, the SERB leader boasted that he “has disrupted the screening of the Russophobe Mansky's film "Summer War," which "glorifies members of the terrorist organization “Azov.”[17]

The other groups limited themselves to verbal attacks, hooligan antics, and threats. For example, on September 2, 2021, on the day of the 80th birthday of the famous human rights activist Lev Ponomarev, insults were written on the door of his office and on the hall floor in his building, and a leaflet was pasted next to the apartment, calling Ponomarev “a defender of terrorists.” Activists of the National Liberation Movement (NOD) came to Cafe MART, where the birthday celebration was taking place, but the security personnel did not let them in.

On May 8, Zakhar Prilepin’s Guard brought to the editorial offices of the Echo of Moscow radio station a lampshade with the inscription "This could have been Shenderovich” and a letter saying that “Under the Nazis, in all likelihood, the unrespectable Viktor would have to serve the Third Reich! In some capacity, anyway – a lampshade, for example…”[18] The Guards were outraged by Shenderovich's broadcast of "Special Opinion" on May 6, during which the host had mentioned the responsibility of the Soviet Union, along with Hitler, for unleashing World War II.

Members of Prilepin’s Za Pravdu (Russian for “For Truth”) came to the Moscow office of Memorial on January 11 and tried to break into the building (which was locked for quarantine) while filming their attempts and shouting, “Look, Memorial is afraid to communicate with the people,” and scattering leaflets that said “Let's rid Stalin of foreign agents!”[19]

During the final hearing on the liquidation of International Memorial (recognized as a foreign agent), activists from the National Liberation Movement (NOD) gathered in front of the Supreme Court building in Moscow, addressed provocative questions to the Memorial supporters, and held signs accusing Memorial of defending Nazi criminals.

Other Attacks

In 2021, we are aware of 1 attack on a homeless person (same as in 2020). This data is obviously too fragmentary and therefore does not tell us anything about the true scope of violence and the dynamics of xenophobic attacks on those whom the attackers call “bio-garbage” and the filth they propose to "cleanse" the country of.

This past year once again saw a case of xenophobic violence in the army, another area that is completely insulated from and inscrutable for the public. Reserve private Ramzan Albakov, “threatening conscript soldiers with physical violence, wrote the word “Ingushetia” with shaving foam on their backs... did a photo shoot against their background and posted these photos on social networks.”[20]

Our data for 2021 include victims who suffered by association – such as a girl who was walking down the street with a dark-skinned companion and those who expressed disapproval of the behavior or symbolism of the ultra-right, like a Yekaterinburg school student, who was beaten for expressing disapproval of Nazi skinheads.

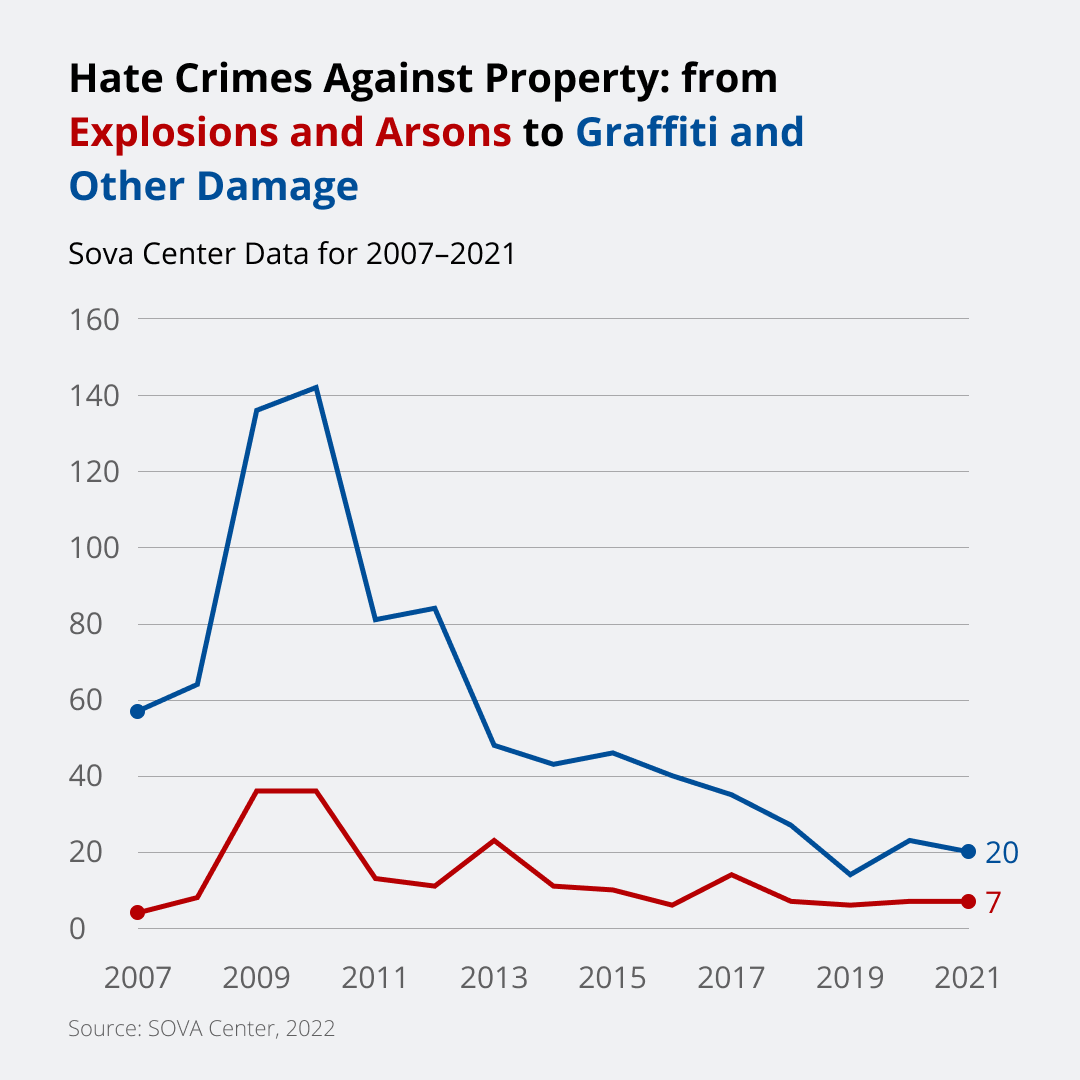

Crimes Against Property

Crimes against property include damage to cemeteries, monuments, various cultural sites, and property in general. They are categorized under several different articles of the Criminal Code, but the enforcement is not always consistent. Such acts are usually referred to as vandalism, but we rejected this term a few years ago, as the term “vandalism,” be it in the Criminal Code or everyday language, clearly does not encompass all possible types of damage to property.

In 2021, the number of religious, ethnic, or ideological hate crimes against property was slightly lower than in 2020: 27 incidents in 20 regions of the country in 2021 (at least 30 in 21 regions in 2020, at least 20 in 17 regions in 2019). Our statistics does not include isolated cases of neo-Nazi graffiti and drawings on buildings and fences, but it does include serial graffiti (law enforcement considers graffiti to be either a form of vandalism or a means of public statement).

In 2021, 13 ideological sites and one government site were targeted;[21] this is higher than the ten attacks on ideological sites and one on a government site recorded in 2020. The sites that sustained damage included monuments to Lenin, Kirov, “Eternal Flame,” and a memorial to the heroes of the Great Patriotic War. A separate case is Navalny’s headquarters in Murmansk, where swastikas were drawn on the walls and the equipment broken. There was also a case of an attack on an LGBT cafe.

As is usually the case, most of these acts target religious sites and objects. As in 2020, Russian Orthodox churches and crosses were the most frequent target of desecration, (four incidents compared to eight in 2020); unexpectedly, pagan sites were targeted equally frequently (four attacks vs. three in 2020). Jewish sites come in second with 3 attacks, just like in the previous year. One protestant site was attacked (two in 2020).

On the overall, the number of attacks against religious sites has decreased: 12 in 2021 (19 in 2020 and 15 in 2019). The number of the most dangerous acts – arson and explosions – has remained the same as in the previous year and the share therefore represents 26%, or 7 out of 27 (7 out of 30 in 2020).

One notable case was setting fire to the building of the Shamir synagogue in Moscow on April 20, that is, on Hitler's birthday. A Swastika was also drawn on the walls of the synagogue.

The regional distribution has changed noticeably. In 2021, this type of crime was reported in 12 new regions: Volgograd, Leningrad, Novgorod, Omsk, Orenburg, Samara, and Yaroslavl regions, Krasnodar Krai, the Republics of Buryatia, Crimea, Yakutia (Sakha), and Tatarstan; the following 14 regions where such crimes have been reported before went off the list: Arkhangelsk, Astrakhan, Bryansk, Vologda, Voronezh, Nizhny Novgorod, Ryazan, and Chelyabinsk regions, the Kabardino-Balkarian Republic, the Altai Republic, Bashkortostan, Khakassia, Krasnoyarsk Krai, and Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug.

And this is the third consecutive year when the geographical spread of the xenophobic vandalism (20 regions) turned out to be wider than that of the acts of violence (18 regions).

Both types of crimes were recorded in nine regions (five in 2020 and 2019): in Moscow, St. Petersburg, and the Moscow, Leningrad, and Kaluga regions, (coincides with the data for 2019), the Omsk and Yaroslavl regions, Primorsky Krai, and Krasnoyarsk Krai.

Criminal Prosecution for Violence

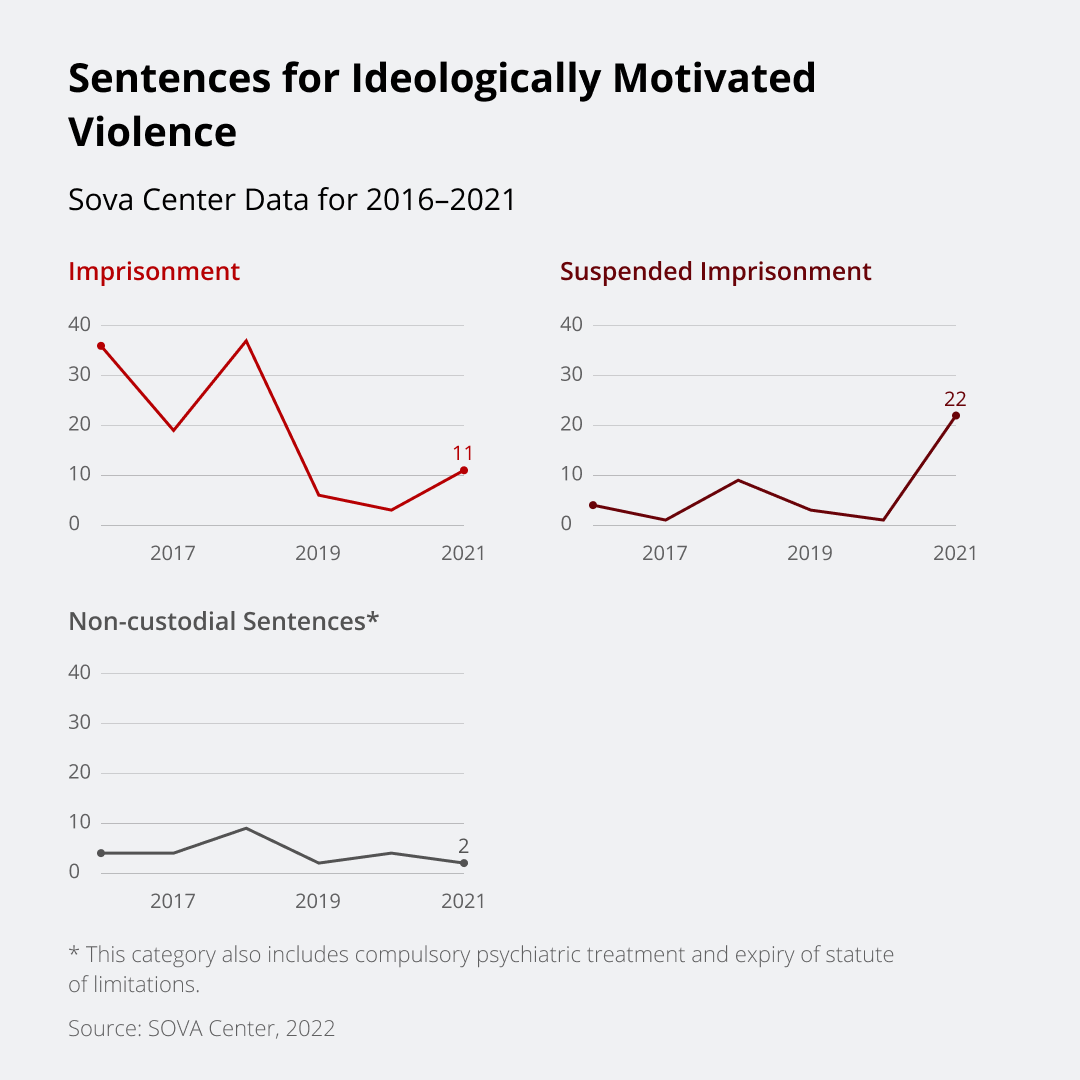

In 2021, the number of those convicted of violent hate crimes was more than four times higher than in the previous year. In 2021, not less than 10 guilty verdicts where the hate motive was officially recognized by courts were issued in 10 regions of the country.[22] Unfortunately, official statistics on sentences with hate motive are not available, since this qualifying feature does not constitute part of an article of the Criminal Code, but only a paragraph, and the sentencing statistics are published by the Supreme Court by parts of the articles. 35 people were found guilty in these trials (eight were convicted in 2020, and 11 in 2019). Most of the convicted were tried in joint trials.

Racist violence was categorized under the following articles containing hate motive as a categorizing attribute: Murder (Paragraph L of Part 2, Article 105 of the Criminal Code), Hooliganism (Paragraphs B and C of Part 1, Article 213 of the Criminal Code), Intentional Infliction of Injury to Health of Average Gravity (Paragraph E of Part 2 of Article 112), Intentional Infliction of a Grave Injury (Paragraph E of Part 2 of Article 111), and Threat of Murder (Part 2 of Article 119). This is a standard set of articles used in the last few years.

In one sentence, Article 117 of the Criminal Code, a quite rare one in our practice, was applied (Torture against two or more persons, against a pregnant woman, against a minor, motivated by hatred) with two qualifying signs (Paragraphs B and Z). This article, together with Article 213 of the Criminal Code, was applied in Tatarstan in the verdict to a local resident Albert Khabibullin for beating pregnant women because of “hostility towards women.”

Article 282 of the Criminal Code (Incitement of Hatred) was applied in two guilty verdicts for violent crimes (in one in 2020). Interestingly, both attacks targeted anti-fascists and and in both cases, suspended sentences were imposed (Paragraph A of Part 2).

In Omsk, young men beat up two people of "non-Slavic appearance" and attacked two "anti-fascist anarchists." The attacks were accompanied by xenophobic insults. On the day of the attacks, the criminals put up leaflets of "right-wing radical content" in the city center. In Ryazan, three young men beat a 26-year-old anti-fascist and shouted humiliating insults. The attack was filmed with a mobile phone.

We believe that in this case it would be more appropriate to apply another article with the categorizing attribute, perhaps Article 111 or 112 of the Criminal Code (depending on the severity of the inflicted injuries). However, this application of Article 282 is also possible: the Resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation of 28 June 2011 No. 11 “On Court Practice on Criminal Cases on Crimes of an Extremist Nature”[23] clarifies that Article 282 of the Criminal Code may be applied to violent crimes if they are aimed at inciting hatred in third parties, for example, in the case of a public and demonstrative ideologically motivated attack.

Penalties for violent acts were distributed as follows:

- 2 persons sentenced to more than 10 years in prison;

- 3 persons sentenced to up to 10 years in prison;

- 1 person sentenced to up to 5 years in prison;

- 5 persons sentenced to up to 3 years in prison;

- 22 persons received suspended sentence;

- 2 persons sentenced to fines.

The suspended sentences in the aforementioned sentences for attacks on anti-fascists are apparently justified by the attackers being underage and by their active repentance. Suspended sentences were also given to other minor members of an ultra-right group in St. Petersburg, who carried out several attacks on "natives of Asian countries," and the members of the ultra-right community in the Kirov region, who carried out at least five attacks on "people of non-Slavic appearance" and "drugs and alcohol users."

In addition, six accomplices of Andrei Kleschin (the famous neo-Nazi Andrei Linok[24]) got off with suspended sentences for attacking an anti-fascist concert at the Tsokol club. Kleshchin himself received 2 years and 3 months in a general regime colony, but did not go to prison, as he was released after serving the term in the pre-trial detention center. Interestingly, Linok has changed his name again, and now he is Ivanov.

In addition to the above, two of the three convicted members of the Black Bloc community, Artem Vorobyov and Dmitry Nikitin, received suspended sentences for participating in an extremist community and attacking two participants of an LGBT conference.[25]

All these sentences, especially in the case of ultra-right gangs like Linok's, raise doubt about the adequacy of the punishments. As is obvious from the example of Linok, sentences such as these do practically nothing to prevent the ideological far-right from carrying out similar acts in the future.

The fines were handed down to one of the participants of the above mentioned Black Bloc community for participating in an attack on LGBT people, and to a minor resident of the Tula region for attacking an anti-fascist.

The others convicted in 2021 were sentenced to terms of various lengths, which seems to be quite proportionate to their crimes. Among those sentenced to prison terms of between 6 and 9.5 years were Andrei Skvortsov and his accomplices, convicted of attacking Kyrgyz citizens in the center of Moscow on July 26, 2019.[26] Earlier, Andrei (Bely) Skvortsov was for some time a member of the ultra-right National Conservative Movement (NKD) headed by Mikhail Ochkin and Valentina Bobrova and was also one of the leaders of the right-wing radical community Cherny Corpus (Russian for “Black Corps”), later renamed White National Unity (BNE).

2021 saw the end of the trial of the widely covered case of the murder of Timur Gavrilov, a 17-year-old medical student from Azerbaijan. 22-year-old Vitaly Vasiliev was sentenced under Paragraph I of Part 2 of Article 105 of the Criminal Code, Part 1 of Article 223 of the Criminal Code (Illegal alteration of firearms), Part 2 of Article 222 of the Criminal Code (Illegal acquisition, storage, transportation of firearms committed by a group of persons by prior agreement), and Part 1 of Article 222-1 of the Criminal Code (Illegal acquisition, storage, transportation of explosives) to 19 years of imprisonment in a high-security penal colony, a subsequent restriction on liberty for one and a half years, and a fine of 100 thousand rubles.[27]

We are aware of several other sentences, which, it seems to us, were handed down for xenophobic violence, although the hate motive was not included in the charge or we are not aware of it. It is significant that three out of four such sentences were handed down for homophobic attacks in Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Yekaterinburg. According to our experience and observations, the homophobic motive is rarely taken into account during court proceedings, and the above-mentioned sentence to the participants of the Black Bloc, where the motive of hatred against LGBT as a "social group" was taken into account, is rather an exception.

Investigations into old criminal cases of murders committed in the early 2000s are also ongoing. They came to light a year earlier,[28] after the news of the arrests of neo-Nazis mentioned in the testimony given by the late Martsinkevich during the investigation into the infamous brutal murder of two people, a video of which appeared online in the summer of 2007. In August, the Main Investigative Department of the Russian Investigative Committee charged Sergei (Malyuta, Boatswain) Korotkikh, another formerly well-known neo-Nazi and a former officer of the Azov regiment, with murder committed by an organized group motivated by national hatred; Basmanny District Court arrested Korotkikh, who is in Ukraine, in absentia.

FSB officers were constantly reporting detentions all over the country of supporters of the organization repeatedly mentioned in this report under the ominous name "Maniacs. Murder Cult" (M.K.U.) (another version is “The Youth that Smiles”). In February, the FSB reported the detention of M.K.U. members in Voronezh,[29] in March in Gelendzhik and Yaroslavl,[30] in April in Irkutsk, Krasnodar, Saratov, Tambov, Tyumen, Chita, Anapa, Pushchino (the Moscow region), and Pereslavl-Zalessky (the Yaroslavl region),[31] in May in the Saratov region,[32] in July in Belgorod. On December 13, the FSB reported that 106 neo-Nazis were detained in 37 regions on suspicion of preparing terrorist attacks and mass murders in Russia,[33] and on December 17 they reported the detention of an M.K.U. supporter who planned an attack on a journalist in the Rostov region.[34] Detentions continued in 2022. As early as on January 11, 2022, the FSB Public Relations Center reported the detention in the Tver region of another M.K.U. member, who planned to commit terrorist attacks on public transport.[35]

Until January 30, 2021, M.K.U. was not heard of anywhere; it was first mentioned in the Rokot and Kremlyovskaya Prachka [The Kremlin Laundrywoman] Telegram channels. Apparently, the M.K.U. group used to be a public page in one of the social networks, where videos of violent attacks and other materials cultivating misanthropic ideas were posted. As the media reported, "initially, the members of M.K.U. were focused on calls for the cleansing of the race, but later began calling for riots and attacks on law enforcement officers.”[36]

FSB reports refer to M.K.U. as a “Ukrainian radical youth group,” based on the fact that it was created in 2018 by a resident of Ukraine, Yegor (Zon, Maniac, the German, Yegor Yakovlev) Krasnov, born in 2000. The M.K.U. Telegram channel published a map showing several groups (or individual participants) located in Russia, Ukraine, and even in some other countries.

Krasnov attracted the attention of Ukrainian law enforcement after the publication of a number of videos that showed beatings and stabbings. On January 10, 2020, the Ukrainian police detained Krasnov after he and two friends attacked a young man with a knife on the Dnieper embankment. Out of at least 10 crimes in Yegor Krasnov’s case, three are being tried in court: an attack on a Syrian, the massacre on the Dnieper embankment, and a “hop-stop” in Taras Shevchenko Park with five victims.[37] Criminal charges have also been filed against him in Russia. On March 11, some ultra-right Telegram channels reported that on March 6 Krasnov was found dead in the Dnieper pre-trial detention center. Later this information could not be confirmed.

Apparently, some of those detained in Russia did commit some kind of attacks and acts of vandalism. But so far not a single trial of M.K.U. has gone ahead. And it is hard to say what exactly those people had to do with M.K.U., just how real this network is, whether it is really an organization or just a Yegor Maniac’s fan club, what connections exist between Russian and Ukrainian participants, how people detained in possession of weapons used those weapons and what exactly they have done.

Criminal Prosecution for Crimes against Property

In 2021, we are aware of three sentences for crimes against property where hate motive was cited; seven were convicted. (In 2020, we reported one sentence against one person; in 2019, we have no information about such sentences.) As is the case with violent hate crimes, the statistics of sentences published by the Supreme Court does not allow us to isolate the data we need: in Article 244 of the Criminal Code on cemetery vandalism, the motive of hatred is a paragraph, not part of the article, and in Article 214 of the Criminal Code (Vandalism) it constitutes part of the article together with deeds committed by a group.

The sentences known to us were unrelated to countering xenophobia: those were the cases of setting fire to the office of the United Russia party and damage to a booth at the Prosecutor General's Office (we question the appropriateness of these sentences). In addition, the justification of the motive of political and ideological hatred or enmity in the article on vandalism is generally questionable.[38]

Another case, under Article 214 of the Criminal Code, for a xenophobic graffiti on the building of the student dormitory of the Rimsky-Korsakov State Conservatory and a residential building in St. Petersburg was terminated. The accused was fined by the court.

In two sentences for neo-Nazi symbols (a swastika painted on the Garden of Memory information stand dedicated to the war dead in Ukhta, the Komi Republic, and neo-Nazi graffiti and inscriptions on the facade of a building in Sevastopol), the hate motive was not taken into account (both acts were qualified under Part 1 of Article 214 of the Criminal Code). In the first case, the attacker was fined; in the second, he was sent to the penal colony, as he had an outstanding criminal record.

_____________________________________________

[1] Our work on this issue was supported by the Norwegian Helsinki Committee and BERTA International. On 30 December 2016, the Ministry of Justice has forcibly listed SOVA Center as “a non-profit organization performing the functions of a foreign agent.” We disagree with this decision and have filed an appeal against it. The author of this report is a Board member of SOVA Center.

[2] Hate Crime Law: A Practical Guide. Warsaw: OSCE/ODIHR, 2009 (available on the OSCE website in multiple languages, including Russian: http://www.osce.org/odihr/36426).

Alexander Verkhovsky. Criminal Law on Hate Crime, Incitement to Hatred and Hate Speech in OSCE Participating States (2nd edition, revised and updated). The Hague: SOVA Center, 2016 (available on the SOVA Center’s website: https://www.sova-center.ru/files/books/osce-laws-eng-16.pdf).[3] Vera Alperovich. “You die and start again from the beginning…” Public activity of far-right groups, summer-fall 2021 // SOVA Center. 2021. 24 December (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2021/12/d45513/).

[4] Vera Alperovich, Natalia Yudina. The Ultra-Right Shrugged: Xenophobia and radical nationalism and counteraction to them in 2013 in Russia // SOVA Center. 2014. 31 March (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/reports-analyses/2014/03/d29236/).

[5] Xenophobia and migrants // Levada Center. 2022. 24 January (https://www.levada.ru/2022/01/24/ksenofobiya-i-migranty/).

[6] Data for 2019-2021 is provided as of 19 January 2022.

[7] In our 2021 report, we reported one dead and 43 injured and beaten. See: Natalia Yudina, “Potius sero, quam nunquam”: Hate Crimes and Counteraction to Them in Russia in 2020 // SOVA Center. 2021. 5 February (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/reports-analyses/2021/02/d43611/).

[8]Here and below, all chart data is based on the monitoring of SOVA Center.

[9] The widow of a Nigerian man who died while rescuing a girl is harassed online // Izvestiya. 2021. 20 July. (https://iz.ru/1196109/2021-07-21/vdovu-pogibshego-pri-spasenii-devushki-nigeriitca-zatravili-v-seti).

[10] For more on this and other inflammatory campaigns of Male State see: Alperovich, “You die and start again from the beginning…”

[11] See: Yudina, “Potius sero, quam nunquam.”

[12] In Moscow, the Armenian-Azerbaijani war starts again. The diasporas mobilize combat-ready members to fight each other // Readovka. 2021. 27 November (https://t.me/readovkanews/23575).

[13] See: Yudina, “Potius sero, quam nunquam.”

[14] Maxim “Tesak” Martsinkevich in Brief // SOVA Center. 2020. 1 October (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/news-releases/2020/10/d42991/).

[15] And also for the release of stories dedicated to family relations in the Caucasus. For more information about threats, see: Alperovich, “You die and start again from the beginning…”

[16] Attacks of this type peaked in 2007 (7 killed, 118 injured); the numbers have since been steadily declining. After 2013, trends have been unstable.

[17] SERB activists attack director Mansky during the Artdokfest festival // SOVA Center. 2021. 9 April (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2021/04/d44027/).

[18] For more details see: Natalia Yudina, The Well-forgotten Old: Hate crimes and countering xenophobia and radical Nationalism in Russia in the first half of 2021 // SOVA Center. 2021. 30 July (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/reports-analyses/2021/07/d44639/).

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ramzan Albakov sentenced to two years of probation. See: A court in Irkutsk sentenced a serviceman to probation for writing on the backs of colleagues while threatening them // Interfax. 2021. 21 December (https://www.interfax-russia.ru/siberia/news/sud-v-irkutske-prigovoril-k-uslovnomu-sroku-voennosluzhashchego-za-nadpis-na-spinah-sosluzhivcev-pod-ugrozoy-raspravy).

[21] Administration of Judicial Department, Moscow.

[22] Only the verdicts in which the hate motive was officially recognized and which we consider appropriate are included in this count.

[23] For more on this see: Vera Alperovich, Alexander Verkhovsky, Natalia Yudina, Between Manezhnaya and Bolotnaya: Xenophobia and Radical Nationalism in Russia, and Efforts to Counteract Them in 2011 // SOVA Center. 2012. 5 April (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/reports-analyses/2012/04/d24088/).

[24] In the past, Andrei Linok headed the right-wing radical gang Lincoln-88, which between August and December 2007 committed at least 12 racist attacks, including two murders, in St. Petersburg. In May 2011, the court found 21 gang members guilty and sentenced 10 of them to terms ranging from 3.5 to 9 years in prison. Linok was released in 2017 and soon changed his name to Kleshchin.

[25] The third person found guilty, Viktor Trofimov, was fined 50 thousand rubles. The leader of the Black Bloc Vladimir Komarnitsky (Ratnikov) fled house arrest on February 15, 2021 and was put on the wanted list. According to some reports, he is in Lithuania and is awaiting political asylum. Another leader, Dmitry Sporykhin, also escaped house arrest at the end of 2020, was put on the wanted list, and arrested in absentia.

[26] Verdict passed for the attack on the natives of Kyrgyzstan // SOVA Center. 2021. 20 December (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2021/12/d45495/).

[27] A medical student from Azerbaijan murdered in Volgograd // SOVA Center. 2020. 23 June (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2020/06/d42576/); The verdict on the murder of a medical student from Azerbaijan comes into force // SOVA Center. 2022. 21 January (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2021/10/d45184/).

[28] Yudina, “Potius sero, quam nunquam.”

[29] Voronezh: preventive measure determined for four detainees // SOVA Center. 2021. 18 February (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2021/02/d43699/).

[30] Members of the M.K.U. group detained in Gelendzhik and Yaroslavl // SOVA Center. 2021. 19 March (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2021/02/d43699/).

[31] Supporters of M.K.U. detained in several cities // SOVA Center. 2021. 29 April (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2021/04/d44136/).

[32] The Saratov region: suspects in the creation of an ultra-right community detained // SOVA Center. 2021. 28 May (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2021/05/d44298/).

[33] Supporters of M.K.U. detained // SOVA Center. 2021. 13 December (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2021/12/d45440/).

[34] New arrest of an M.K.U. supporter // SOVA Center. 2021. 17 December (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2021/12/d45479/).

[35] Another arrest of an M.K.U. supporter // SOVA Center. 2022. 11 January (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2022/01/d45587/).

[36] Extremism found on the fence // Kommersant. 2021. 18 February (https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/4694712).

[37] Andrei Soshnikov. What is M.K.U. Talk about the "cult" of murders created by Ukrainian skinheads and its followers in Russia // Nastoyaschee vremya. 2021. 26 March.

[38] For more on this see: In Moscow, three activists were found guilty of vandalism motivated by political enmity // SOVA Center. 2021. 11 May (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/persecution/2021/05/d44184/).